23 Jan, 1950

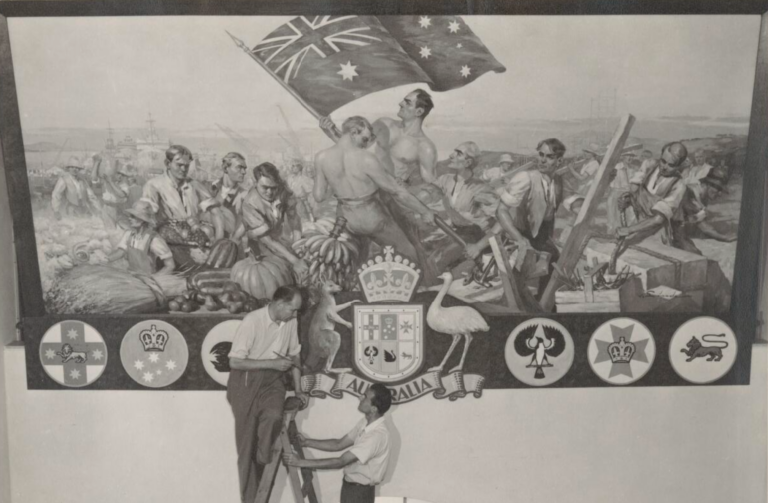

Australian Citizenship Conventions

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.