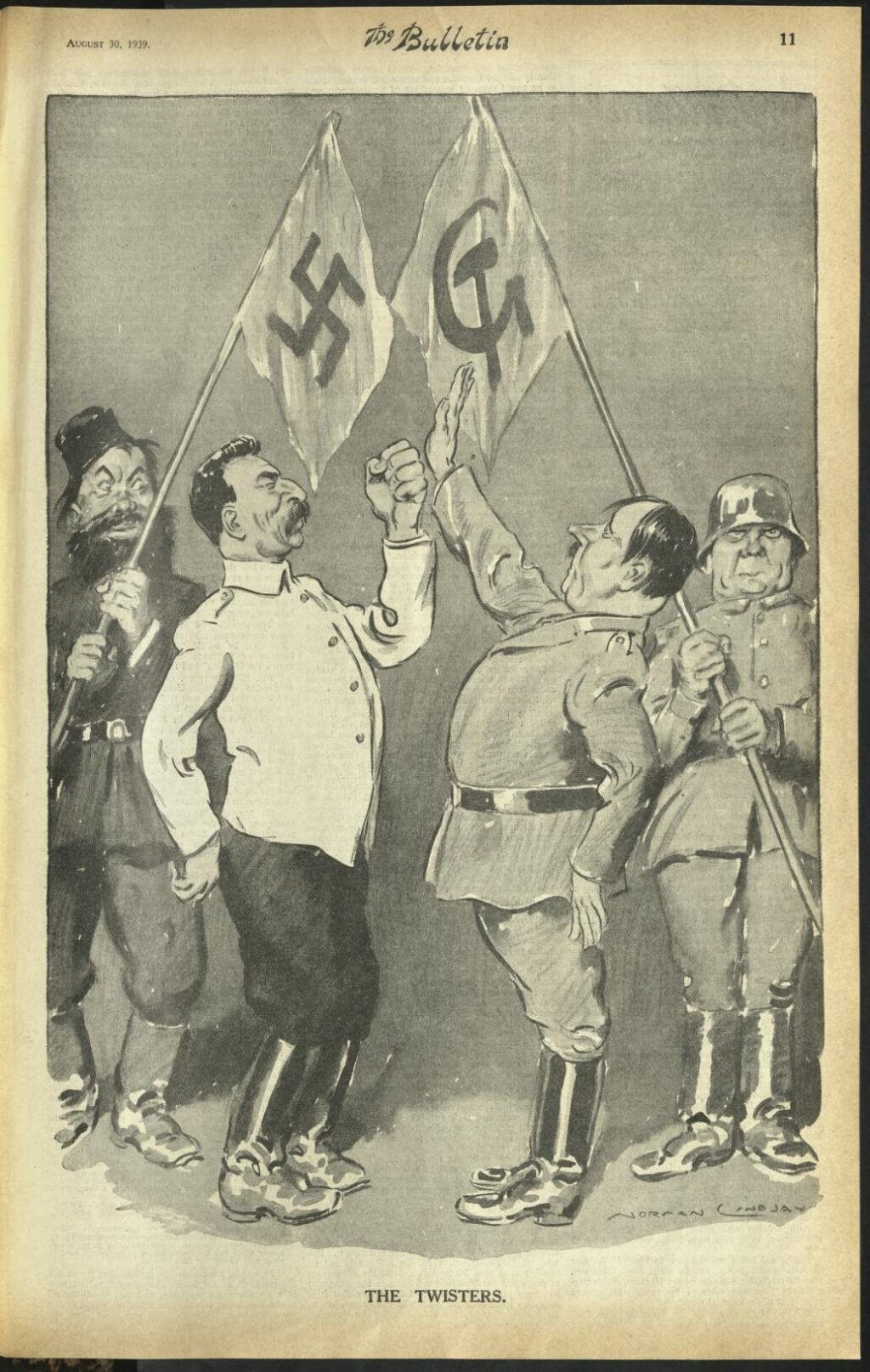

On this day, 23 August 1939, late edition Australian newspapers report the shocking news that Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union had signed a non-aggression pact. The pact indicated that Germany would now be free to invade Poland knowing that in the event of a Second World War the Allies would be robbed of the Russian assistance they had enjoyed from 1914-March 1918. Secretly, the pact indicated something even more sinister; that the governments of Hitler and Stalin had signed a supplementary protocol dividing up Eastern Europe between themselves, and that the USSR would actively assist the Nazi’s by invading Poland from the East.

Prime Minister Robert Menzies was stunned by the sudden turn of events, telling reporters:

‘The news is unexpected. In the absence of precise official information it is not possible to state the effect of the reported pact or the reason for its adoption. It is difficult to reconcile the report with the fact that negotiations between Britain and France and the Soviet Union are actually on foot, and have made considerable progress. If the reported pact is more than a genuine agreement against aggression, and foreshadows a close association between Germany and Russia, it is impossible to reconcile it with Herr Hitler’s repeated claim to be Europe’s bulwark against Russian communism, about which he has spoken so much, or with Germany’s inclusion of Japan in an anti-Comintern pact [an alliance signed between Germany and Japan in November 1936 explicitly to combat communism]. Japan may well wonder just where she is. It will also be well for Russia to remember that in 1934 Hitler made a 10-years’ non-aggression pact with Poland, which he recently cancelled, and that in September last at Munich he made, in effect, a pact of peace with Great Britain.’

Menzies’s statement reflected the fact that Russia and Japan had been fighting a border war near Manchuria, however by 15 September they had arranged a ceasefire which helped to facilitate the Soviet invasion of Poland on 17 September. The Soviets justified their move as an attempt to protect Russians living in Poland, leading Menzies to circumspectly tell Parliament:

‘Last week the Soviet Government mobilized very large forces along the western frontier of Russia. The purpose of this became evident when, on the 17th September, Russian troops crossed the Soviet-Polish frontier at points along its whole length, and proceeded to occupy Polish territory in the face of resistance. According to the official explanation given out in Moscow, this act did not mean that Russia had abandoned its neutrality in the war. It signified only the determination of the Soviet Government to protect from the consequences of the military collapse of the Polish State, the White Russian and Ukrainian populations which had previously belonged to Russia.

A final opinion, either on the Russian motive or on the limits of the action undertaken, is not yet possible; but, even as it stands, the Soviet action is hard to justify by the arguments put forward in Moscow. It has been suggested in some unofficial quarters that Soviet occupation of the eastern territories of Poland may be the price to which Germany agreed for the German-Soviet Pact of nonaggression. It has also been suggested that the Soviet action may be the measure of Russian fears of what might follow from the precipitate German eastward advance.

However this may be, there is nothing as yet to show whether or not this move portends any wider Soviet intervention in the war. On the other hand, and although the news initially presents disquieting features, there are some factors about the Russian act which should not be overlooked.

It is impossible to feel that Germany and Russia, between whom a deep-seated enmity and mutual suspicion has existed for many years can at a moment’s notice compose their hereditary differences and satisfy their own people. A common frontier may well accentuate differences of outlook and policy, and it seems probable that, until the Russian intentions are clarified, Germany will be forced to maintain substantial forces in the east which would otherwise be available for operations on the western front.’

While the Soviet Union never officially joined the Axis powers, it did go rogue, using the opportunity provided by the war to invade Finland on 30 November 1939. Following the Soviet lead, Australian communists would vehemently resist assisting the Allied war effort, leading to chronic industrial strikes which lasted until the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was destroyed by Operation Barbarossa in June 1941. It was in these circumstances that Robert Menzies would first ban the Communist Party in June 1940 – along with a number of fascist groups. As Menzies would later describe in his Forgotten People radio broadcasts, he saw fascism and communism as two sides of the same authoritarian coin, and that the real choice was ‘between Communism or Fascism on the one hand, and an enlightened Liberal system on the other.’

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.