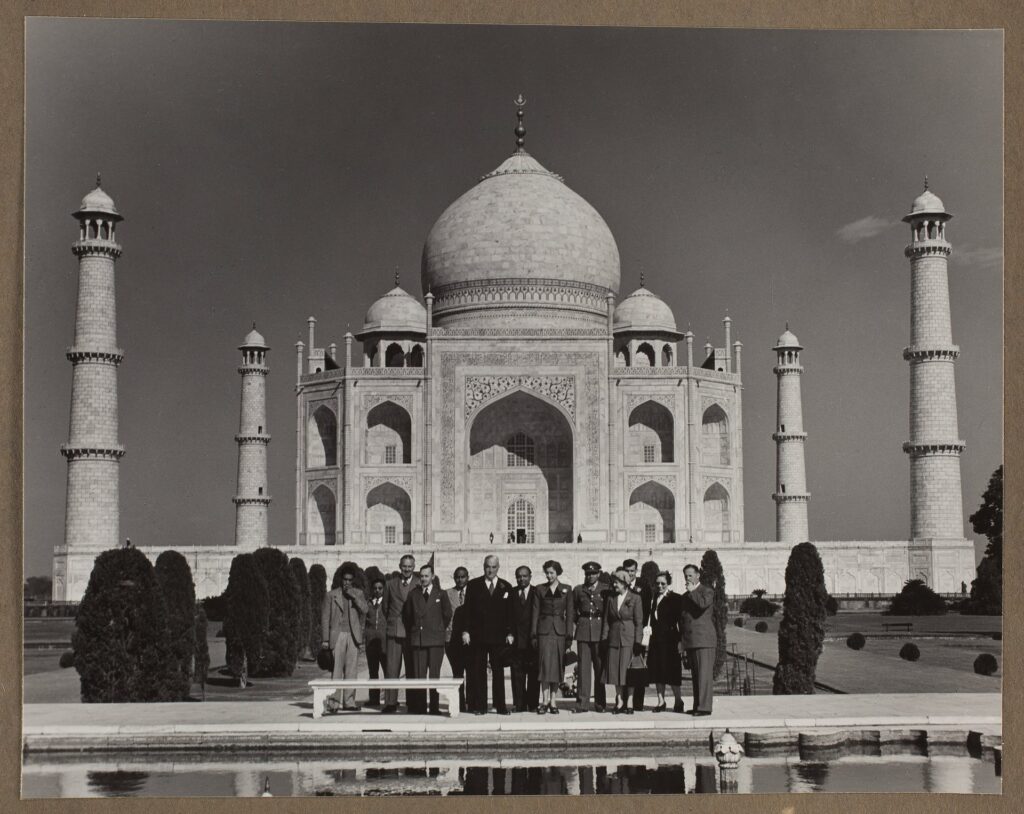

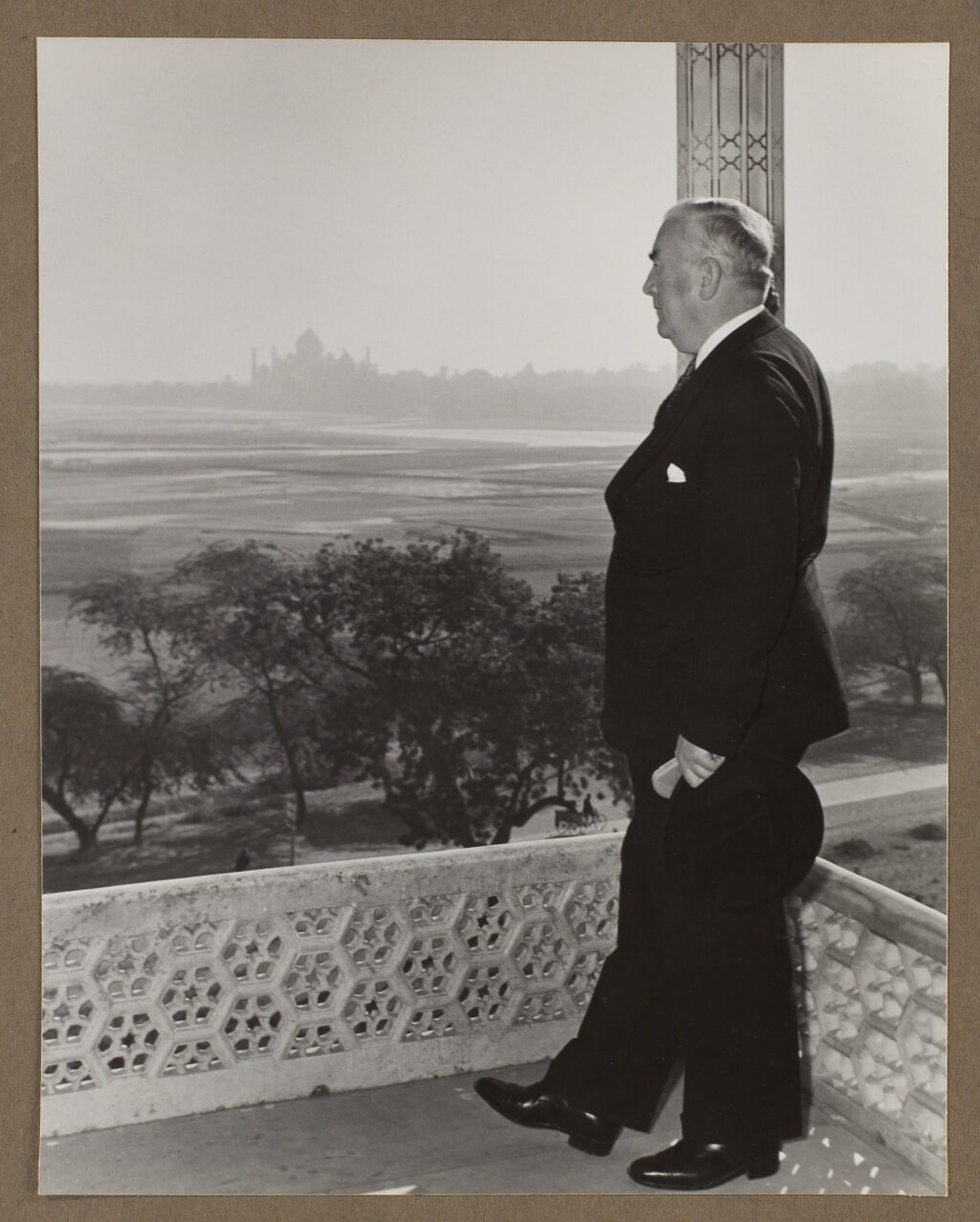

On this day, 28 December 1950, Robert Menzies delivers a landmark address over Indian radio, as he becomes the first Australian prime minister to visit the newly independent republic.

Menzies’s relationship with India was admittedly somewhat fraught. He had been one of many who warned against a rushed transition to becoming an independent democracy, believing that ‘the art of self-government cannot be learned in a day’ and that there were large obstacles to be overcome if an independent India were to prove a success – while reiterating that ‘I have always sympathised profoundly with those highly-educated and forward-looking people of modern India in their impatience for full sell-government’. In March 1942 Menzies had delivered a broadcast on ‘The problem of India’ as part of his forgotten people series, and in it he warned that ‘the problem of how and by what stages you confer self-government of the Dominion type upon scores of millions of people of various races and religions and with a still high percentage of illiteracy is not a simple one’. As the ‘dominion’ reference indicated, Menzies would end up very disappointed to see India become a republic, as opposed to self-governing under the Crown in the manner of Australia. This was because he was a fierce believer in the potential of the Commonwealth to act as a force for global good, and thought that a common allegiance to the Crown was vital in tying the Commonwealth together.

Partly as a consequence of these views, historian Meg Gurry has accused Menzies of showing ‘a lack of interest in India’ and failing ‘to develop a relationship of any substance with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’. Sybil Nolan has given added credence to this perspective, by pointing out how Menzies’s personal gifted copy of Nehru’s The Discovery of India appears to have gone completely unread. There is little doubt that Menzies, who appreciated the good the British had done for Australia in laying the foundations for our system of parliamentary democracy and common law, was somewhat uncomfortable with Nehru’s emphasis on the harm the British had done to India. But he was far more uncomfortable with Nehru’s positioning of India as a ‘nonaligned’ country amidst the ideological bifurcation of the Cold War. In these circumstances, not only was India explicitly not Australia’s ally, but its opposing views actively worked to undermine the unity of the Commonwealth (which it remained a part of despite eschewing the Crown), and therefore greatly weakened the multinational association’s influence.

Because of all of these limitations, Menzies is generally given little credit for what he did do to foster closer ties, such as spearheading the adoption of the Colombo Plan aid package to fund regional development and helping to train large numbers of Indian students. Above all this pivotal moment in 1950 has been all but forgotten:

‘I am grateful for this opportunity, through All India Radio, of speaking for a few minutes to the people of India. Of necessity my visit here has been a short one – far too short… I have of course met you prime minister and other leaders of your country; I have glimpsed a little of this historic capital; and I think I have been helped to know a little more, and understand a little more – or, if I may put it this way, I have been helped to tune-in a little more finely to your great country.

I should have liked to visit India at a time of more leisure and less anxiety – for the present is a time when there undoubtedly is a feeling of anxiety throughout the world, with us in Australia no less than with you in India. We Australians are enthusiasts for peace, as you are. We have been doing, and will continue to do our utmost to preserve it. At the same time, I was convinced when my Government came into office a year ago, and I am more than ever convinced now, that we must be well prepared, in case we are unable, despite all the efforts of peace loving nations, to preserve that peace. I am glad, therefore, of the opportunity of again meeting our Commonwealth colleagues in London, and of visiting India on the way. This surely is a time when we must co-operate with one another to the fullest, pool our experience and whatever wisdom we may have, in an all-out effort to preserve those things which we are agreed in regarding as of basic and essential value.

This is my first visit to the capital of India, but because of those basic values which I have in mind – freedom, democratic right and the rule of law – I can hardly feel myself a stranger in this country. There is something refreshingly familiar in much that I have heard and seen and talked about here; there is even something familiar in speaking to you on the radio like this, as I regularly do to my own countrymen. In short, there are common principles, ideals and methods which we share, quite irrespectively of the obvious differences in our historic and cultural backgrounds. For the Australian visiting India there is much common ground to be found; it is pleasing to us, and I believe pleasing to you.

But apart from these broad impressions, it is a fact that in recent times we in Australia have come to learn a good deal more about India than we did a generation ago. For more than a decade now we have had governmental relations with India, first in the trade sphere and later in the political and diplomatic spheres. Nowadays in Australia we have many visitors from India, businessmen, students, officials, tourists, and not least, sportsmen. I think you will agree that even if we had no other link our mutual enthusiasm for cricket would tend to draw us together. Only since the last war have students from India and other Asian countries thought of coming to Australia for their studies. They are more than welcome, as any who have gone there will tell you. Apart from those students who have gone privately to Australian universities or technical colleges, we are glad to have been able to offer for 1951 fifty fellowships and scholarships to Indian students for technical training as part of the Colombo Plan for technical assistance in South East Asia.

This trend, I feel sure, is one of the most valuable in promoting greater knowledge and closer understanding as between our two countries. For it is the hands of the younger generation, obviously, that the future of both our countries and of international relationships ultimately lies. A fact which strikes even the casual visitor to India is the great numbers of young people among you. This, I believe, is due to the fact that the expectation of life in India is tragically short. Nevertheless, it does mean that youth looms large in your population, and this is something of which I think India should take full advantage, by making every effort to train her youth to enter skilled trades and professions, and particularly to encourage her youth to enter public life. As a neighbour of India and a fellow member of the Commonwealth, Australia, within the limits of her resources, will gladly do all she can to assist India in training her immense manpower in the effort to raise her living standard.

I uses the expression “neighbour” because the time has long passed when Australia was a remote and isolated colony, building up her own economy with little or no consciousness of the Asian countries which were her nearest neighbours. The concept of regionalism, envisaged in the Charter of the United Nations, is a comparatively recent one. We in Australia are convinced that it is a most useful and progressive concept in the modern world. Already it has encouraged nations to cultivate one another more, gradually to build up a common pool of experience and resources, to assist one another in solving common problems. Already in the South East Asian Region more than one international meeting in Delhi has proved the usefulness and effectiveness of regional thinking. An even more recent example of the same trend was the Colombo Plan for the economic advancement of South East Asia.

It strikes me that here in India you may perhaps have developed some sort of regionalism in the integration of your states. As I understand it, instead of states operating as separate and possibly rather isolated entities, they have grouped themselves together in mutual interest and have so facilitated their integration into the whole united India. That achievement is a remarkable and historic one. It is a matter of regret and sorrow that I was not destined to make the acquaintance of the architect of that great scheme, Sardar Patel. Indeed, it may well be that the integration of the states and provinces into One India may provide some sort of pattern upon which a regionally conscious human race will one day merge itself into something like One World.

We in Australia in recent years have followed events in India with much interest and sympathy. Without, I must admit, being closely familiar with many of the detailed issues, we admired the long struggle of Mahatma Gandhi in his crusade for nationhood. There were – perhaps there still are – a few people who talk in antique terms of “the loss of India”. I would prefer to speak of the “gain of India” — the gain of a freely-choosing India by the Commonwealth to which, as you well know, we in Australia are deeply devoted.

We followed with interest the building of India’s constitution, and we have seen the heartening spectacle of a modern democracy flourishing in a land of age-old culture. In building her constitution India consulted the constitutions and drew on the experience of other democracies, including, I am proud to say, our own.

We watched with dismay and sympathy the tragedy enacted in Northern India following so closely on the celebration of your independence. And we admired the resoluteness and the success with which your leaders, then so recently in command, met the challenge of lawlessness and averted what might have been an irreparable disaster.

And now we shall follow with no less interest your next important step, when many millions of your countrymen will go to the polls next year to record what I think will be the largest democratic vote ever cast in history.

My visit to Delhi as I said has been all too short, but I am pleased to have had even this opportunity of glimpsing the ancient-cum-modern city which, if it is not India, is after all the heart of the new India. It is well that when Indians and Australians meet, whether at United Nations gatherings or at Commonwealth Conferences, they should have had the additional advantage of having met one another on their own home ground. I am deeply grateful to the Government and people of India for the hospitality and courtesy shown to me here, and I sincerely hope there will come a time when it will be possible for your Prime Minister, Pandit Nehru, to pay a visit to Australia.

To all listeners, and to all the people of India, I send on behalf of myself and the Australian people, warmest wishes for a happy, prosperous and peaceful year in 1951.’

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.