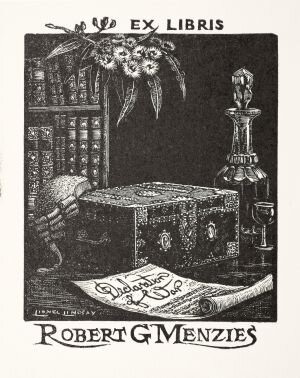

On this day, 3 September 1939, Prime Minister Robert Menzies tells the Australian people that they are at war with Nazi Germany, plunging the nation into a new global conflict scarcely two decades after the previous one had ended. At 9.15pm, broadcast on every national and commercial radio station in Australia, Menzies sombrely addressed his audience of ‘Fellow Australians, it is my melancholy duty to inform you officially that, in consequence of the persistence of Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her, and that, as a result, Australia is also at war.’

Menzies’s choice of words were deliberate. Earlier in the year there had been a debate in the House of Representatives as to whether Britain declaring war meant that Australia was automatically at war, and Menzies held the view that this was the case as the British sovereign was indivisible. This view was contested by certain other ‘Dominions’, namely Canada and South Africa, who had more fully ratified the Statute of Westminster.

Menzies went on to say ‘No harder task can fall to the lot of a democratic leader than to make such an announcement’. Menzies was understandably reluctant, more than 60,000 Australians had lost their lives in the Great War, and nearly 40,00 would die in the new war that his speech was ushering in.

Born out of a deep-seated compassion for humanity and an appreciation for the direct responsibility political leaders must take for their decisions, this reluctance has subsequently given fuel to accusations that Menzies was an ‘appeaser’ and more fallaciously a Nazi sympathiser. The first is not so much inaccurate as it is quite anachronistic. Anyone who had lived through the horrors of the First World War would want to avoid a repetition as long as they still glimpsed even a small possibility of an alternative. Menzies himself had not served in the AIF, but his brothers had and many of the members of his Cabinet had. Both Menzies’s predecessor Joseph Lyons and his Labor successor John Curtin were equally determined to see Australia escape such a fate, even if there were debates over how much money the Government should spend preparing for the possibility that it could not be avoided, with Labor frequently criticising the UAP for increasing the defence budget and making preparations for national service. The attitude now dubbed ‘appeasement’ was all but pervasive in Australian politics.

That is not to say that there was nobody who saw that Hitler was not a man who could be negotiated with, and who urged that military resistance be employed at an earlier stage. The obvious example is Winston Churchill, and he should be praised for his foresight. However, the fact that Churchill only became Prime Minister once his prophecies had proven true is telling. In the political climate of the late 1930s it was the electorate, as much as the political leaders, who insisted on avoiding war at practically all costs. As late as November 1940, after Hitler had already conquered much of Europe, Theodore Roosevelt won an election landslide in the United States explicitly promising to keep his country out of the conflict.

In a wartime radio broadcast made in early 1942, when Japanese troops were rapidly thrusting towards Australia and everyone was looking to point fingers of blame, Menzies pointed out the honest truth that society as a whole had been wrong on the issue. In an address titled ‘Why Aren’t There More Aeroplanes In The Far East?’ he argued that the nation had to hold collective responsibility for not facing up to the likelihood of war earlier, saying that in:

‘1935 a Defence Budget, not of £250m. as in this year, but of £20m. would have been regarded as a piece of war-mongering hysteria. Why on earth shouldn’t we be honest with ourselves about these matters?’

In the early 2000s much was made of the ‘discovery’ of a letter Menzies had written to his High Commissioner in London Stanley Bruce which showed that as late as the 11th of September 1939 Menzies still entertained the possibility of negotiating with Hitler to avoid a prolonged struggle ‘in which Germany’s defensive position is incredibly strong, in which in the long run millions of British and French lives would be lost’. He thought that the war might sap the western powers to such a degree that law and order would breakdown, hence democracy might be destroyed through internal threats rather than external. Menzies also said that his views needed qualification and that he was essentially thinking out loud to a friend, but this aspect of the letter was inevitably downplayed by those who wished to claim its significance. The media discussion prompted Menzies’s biographer A.W. Martin to write an essay explaining why he had omitted the letter from his book. His argument was that all the letter did was prove what we already knew; that the lives of the Australians Menzies was committing to the war were weighing heavily on him. For a leader in such a position to have no doubts would surely be monstrous in itself. By the time Poland fell in early October, Menzies wrote to Bruce saying that the war must go on.

The accusation that Menzies was a Nazi sympathiser relies on privileging a few wayward sentences in a letter to his sister, written during a semi-official trip to scope out Germany in 1938, over literally thousands of public and private descriptions of his disgust at what the Nazis stood for (including ones made before and during 1938), and even other letters from the same trip that are far more negative. In the letter in question, Menzies wrote that while he would be ‘glad to escape’ from its ‘somewhat queer atmosphere’, ‘it must be said that this modern abandonment by the Germans of individual liberty and of the easy and pleasant things of life has something rather magnificent about it. The Germans may be pulling down the churches, but they have erected the State, with Hitler as its head, into a sort of religion which produces spiritual exaltation that one cannot but admire and some small portion of which would do no harm among our somewhat irresponsible populations’.

These are certainly uncomfortable words to read, but it must be emphasised that what Menzies was ‘admiring’ was the strange phenomena of the German people’s apparent enthusiasm for fascism, rather than ever going so far as to express support for its tenets. Menzies was not someone who supported the ‘abandonment’ of individual liberty, his entire career testifies to that. As a man whose religious convictions were personal and outwardly subdued, the idea of worshipping the state was likewise incongruous. In 1938 he was writing at a time when democracy seemed to be assailed by extremist threats from both the left and the right, and he ultimately concluded that democracy needed to find a way to replicate some of the enthusiasm elicited from fascism in order to preserve those very liberties that differentiated democracy from fascism. Just three days after the letter in question, he was recorded in The Times as saying that ‘if our democracy is to survive and flourish, and the liberty which is its lifeblood is to remain pure and strong’ there needed to be a greater ‘willingness to serve the community’. Menzies did not want to create an Australia from which he would be ‘glad to escape’ and once it became clear that Hitler presented a serious threat to the continued existence of parliamentary democracy not just in Poland but throughout the world, Menzies never flinched in his resolve to see him defeated.

You can listen to Menzies’s fateful speech here: https://www.nfsa.gov.au/collection/curated/menzies-speech-declaration-war

Further Reading:

A.W. Martin, ‘Menzies and Appeasement: Understanding Provenance in Reading Historical Documents’, in The ‘Whig’ View of Australian History And Other Essays (Melbourne University Press, 2007).

A.W. Martin, Robert Menzies, A Life: Volume 1 1894-1943 (Melbourne University Press, 1993).

Troy Bramston, Robert Menzies: The Art of Politics (Scribe Publications, 2019).

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.