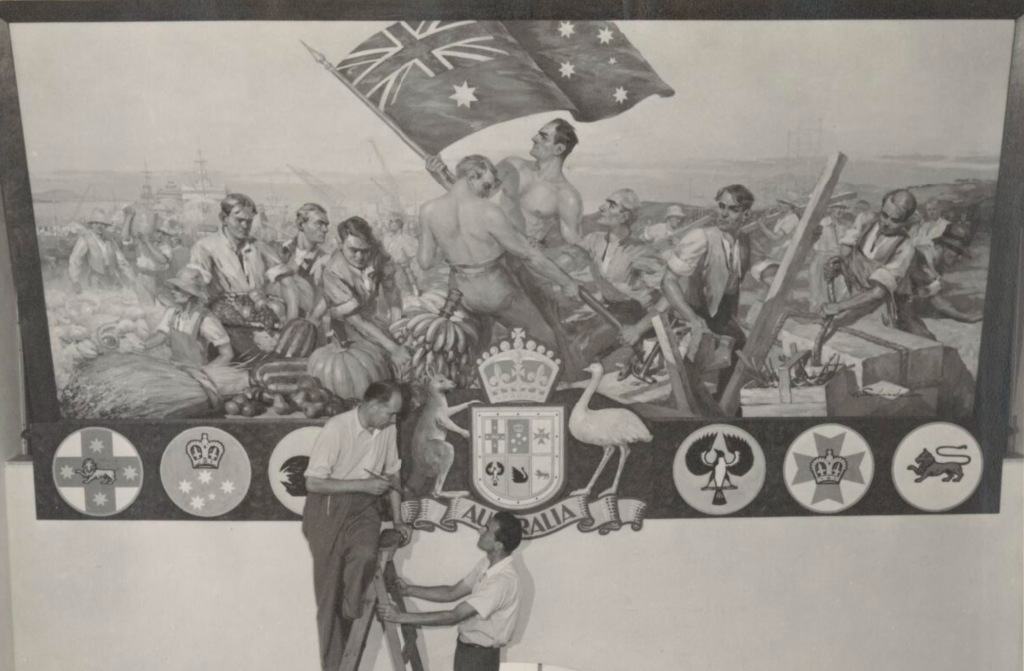

On this day, 23 January 1950, Robert Menzies opens the first Australian Citizenship Convention to discuss plans for how to successfully integrate the 200,000 migrants who had arrived in Australia during the previous five years. Over 200 delegates from church groups, voluntary bodies, employer and employee organisations, state governments, and the media gathered in Canberra to develop ‘ways and means of stimulating a love of citizenship among the population’. Proceedings spanned five days, and included an exhibition in which recent migrants were encouraged to produce artworks celebrating Australian life.

These Conventions would go on to become an annual event and mainstay of the Menzies era, which saw high levels of immigration go hand in hand with the maintenance of social cohesion. They encouraged the entire Australian community to become active in helping migrants to settle, a goal which would be put into practice by what was dubbed the ‘Good Neighbour Movement’.

Menzies’s 1950 keynote preached both the need for tolerance and the great contribution that recent migrants were making to Australia’s national development, telling his audience that:

‘Australians should strike down the insular conception of objecting to a man because of his race or religion. Prejudice against a man because of his origin or beliefs was a sign not of pride but of stupidity.’

While Australia is predominantly an immigrant nation, the issue of immigration has always been politically vexed throughout our history. From an early date, Australians were blessed with high wages and levels of prosperity that were the envy of the European countries from whence they had come. In part due to the combination of a scarcity of workers and the profitability of export enterprises like the wool trade. Hence, there was often resistance to the arrival of new migrants who might offer competition and thereby undercut wages. Australian democracy was arguably birthed in the campaigns to end convict transportation, and convicts were seen as a particularly pernicious form of labour competition since they did not have to be paid. During the gold rush, a similar desire to hoard Australia’s wealth resulted in a number of outbursts against people of Chinese descent.

These xenophobic attitudes led to the introduction of the White Australia Policy, which was in part based on the premise that white immigrants would demand higher wages and therefore were less of an economic threat to Australia’s working class than non-white migrants. However, there was a competing pro-immigration imperative to grow Australia’s population so that the economy could expand and we would be better placed to defend ourselves in the event of war. And relying almost exclusively on migrants from the British Isles greatly restricted our ability to expand in such a fashion.

It was the trauma of World War II which made the drawbacks of narrowing our immigration intake very clear, as Australia faced the threat of invasion by the Japanese and would not have had the manpower to fight them off without the huge assistance provided by the United States. Moreover, the war devastated Britain’s young male population and birthrate, meaning that there were clearly going to be less British migrants available once the war was over.

Menzies realised the need to broaden Australia’s migration. But he also realised that this might be politically very unpopular, hence he felt the need to use one of his Forgotten People radio broadcasts to sell the idea:

‘The greatest guarantee, not only of the safety of Australia but of its future material prosperity, would be a population of at least twenty million. If we are to rely on natural increase, this goal cannot be achieved for a century or two – and with our present population we may not hope to last so long as an independent people. The inevitable deduction from this is that we must have a positive, active and vigorous encouragement of migration. Yet, if you turn your minds back you will recall that for fifteen years before this war there was an attitude of mild hostility on migration into Australia. Are we proposing to resume this outlook when the war is over? Are we going to be timid about the temporary effect, social and industrial, of large migration, or are we to see in it a real source of strength? It is curious that a race so mixed as our own, which derives its strength and resilience from its mixture of English, Irish, Scots, Welsh, Cornish and, going back further, the Celt, the Angle, the Saxon, the Norman, should have become recently so sensitive about the purity of its blood. Migration into Australia, particularly from Northern European counties, will in the long run bring to us nothing but vigour and advantage.’

By the close of the war, there was bipartisan agreement on the need to let in a broader range of migrants, in a manner that was begun under the Chifley Government and would be maintained and in some cases expanded by Menzies once he came to power in 1949. But while both major parties agreed on the necessity of migration, it was still an issue on which the Australian public had to be courted and convinced.

Hence the introduction of the elaborate and expensive Citizenship Conventions, which would be held around Australia Day each year. When the first one was held in 1950, the entire concept of Australian Citizenship was only a year old. Having been introduced by the Nationality and Citizenship Act which came into effect on 26 January 1949. Prior to that, Australians had simply been considered British subjects, largely interchangeable with someone in Canada or New Zealand. Indeed, it was Canada that had set the precedent of creating its own distinctive citizenship, hence the Chifley Government’s decision to follow suit was made to deal with this changed circumstance, rather than being a self-conscious move towards greater independence. Nevertheless, Australia Day was a popular holiday on which Australian values were celebrated, and it made sense to use the day to try to inculcate migrants with those values, and reassure the general public that they would uphold them.

The latter was initially the main aim of the Conventions, which has led to them being criticised for failing to meet or even properly consider the needs of migrants, who back then had far less support services than they do today. But despite this drawback, the Conventions were very successful in subduing anti-immigrant feeling, which is the main reason why the government was willing to spend large amounts of money on them. In 1952 the Federal Treasurer Arthur Fadden tried to cut the Citizenship Convention from the budget, only to be told by Immigration Minister Harold Holt that there was quote ‘still too much anti-immigration and anti-alien sentiment to abandon the best weapon we have yet found to combat it’.

As the decade wore on, the Australian public became more accepting of so-called ‘new Australians’, a shift which was helped in no small part by the prosperity and full employment the Menzies Government was able to achieve. The Citizenship Conventions themselves came to reflect this new and more positive reality. By the late 1950s they talked less about being British and more about simply being Australian. They likewise started to have migrant groups directly represented in their proceedings, who were thus given a platform to tell the government directly what they wanted or needed.

Perhaps most importantly, by 1959 the Conventions stopped talking about a goal of complete assimilation and instead spoke of the milder ‘integration’, i.e. that migrants would have to become part of one Australian community but they could also keep much of their heritage and identity. For this reason, historians have argued that you can use the Conventions to track how the policy of assimilation was gradually eroded. Leading to an Australia that is far more open to other cultures and ways of life.

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.