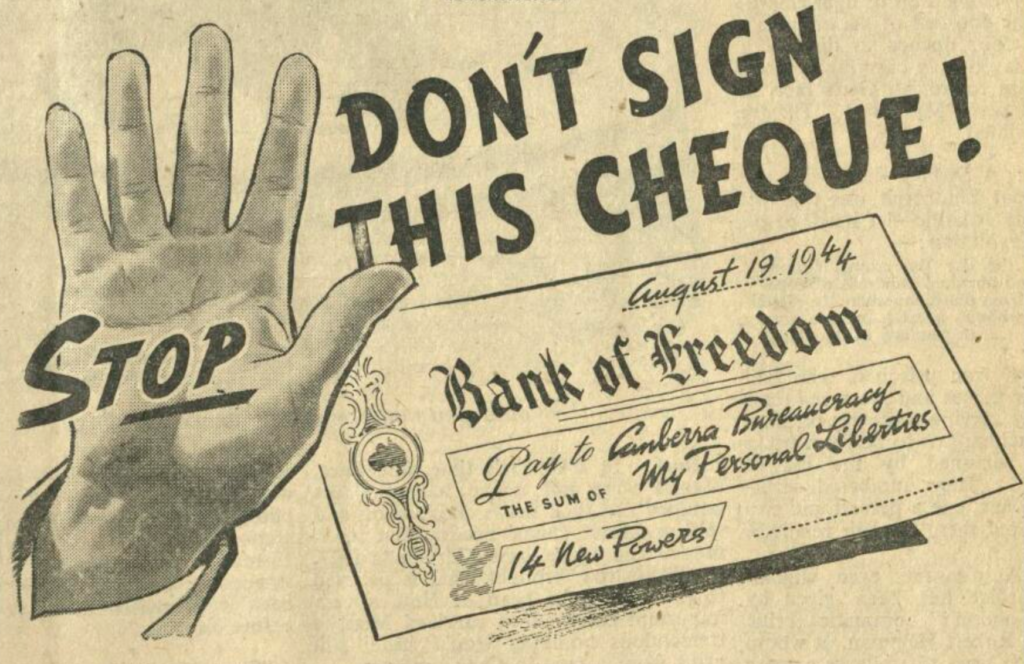

On this day, 19 August 1944, the Curtin Government’s ‘14 powers’ referendum is defeated with a 54.01% ‘No’ vote. The event marks the first tangible victory for Opposition Leader Robert Menzies since taking over the UAP leadership in the wake of the devastating 1943 election defeat, and will provide crucial momentum leading into the founding of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Menzies had presaged forming a new party to champion the principles of Australian liberalism in the immediate aftermath of the 1943 poll, but at the time there was little reason to expect success. After all, numerous new parties of the centre-right were being formed at this time, such as the Queensland People’s Party or NSW’s Liberal Democratic Party – but this fracturing was precisely one of the main problems that had led to the electoral wipeout. In order for Menzies to have any hope of fairing better than the others, he needed to first get on the political front foot, so that liberal and conservative Australians could be inspired behind the idea that they were backing a winner.

In this sense, Menzies was very lucky that the extent of Labor’s victory had given it the confidence to push ahead with the most ambitious program of constitutional change ever attempted in Australia. Wiser heads may have urged caution given that up until this point only 3 of 18 attempts at amending Australia’s constitution had ever succeeded, and no attempt ever introduced by a Labor government had gotten up.

As the ‘14 powers’ label implied, what was officially dubbed the ‘Post-war Reconstruction and Democratic Rights’ referendum sought to give the Commonwealth Government a full 14 new powers over:

i) repatriation of returned soldiers ; ii) employment and unemployment ; (iii) organised marketing of commodities ; (iv) companies, but so that any such law shall be uniform throughout the Commonwealth ; (v) trusts, combines and monopolies; (vi) profiteering and prices (but not including prices or rates charged by State or semi-governmental or local governing bodies for goods or services); (vii) the production and distribution of goods, but so that, (a) no law made under this paragraph with respect to primary production shall have effect in a State until approved by the Governor in Council of that State; and (b) no law made under this paragraph shall discriminate between States or parts of States; (viii) the control of overseas exchange and overseas investment; and the regulation of the raising of money in accordance with such plans as are approved by a majority of members of the Australian Loan Council ; (ix) air transport; (x) uniformity of railway gauges ; (xi) national works, but so that, before any such work is undertaken in a State, the consent of the Governor in Council of that State shall be obtained and so that any such work so undertaken shall be carried out in co-operation with the State; (xii) national health in co-operation with the States or any of them; (xiii) family allowances; and (xiv) the people of the aboriginal race.

Remarkably, all 14 powers were being asked in a single ‘take it or leave it’ question, allowing no option for the Australian people to discern between the merits of each. This was not a new tactic for the ALP; they had done the same thing in the 1911 Legislative Powers Referendum, in which the Commonwealth sought powers over ‘trade, commerce, the control of corporations, labour and employment, including wages and conditions; and the settling of disputes; and combinations and monopolies’ – all at once. When this attempt was heavily defeated with a ‘No’ vote of over 60%, the Fisher Government had reluctantly decided to split up the questions and ask again in 1913 – this time achieving a series of far more respectable and narrow defeats.

Curtin, and particularly his ambitious Attorney General HV Evatt, were thus trying to defy a considerable amount of history. They thought they could succeed in large part because they were so politically ascendent, but also because they had backed down from even more wide-sweeping centralisation. As first proposed by Evatt in 1942 (in a speech in which he largely condemned Australia’s existing constitution in its entirety), the referendum would have asked that ‘the power of the Parliament shall extend to all measures which, in the declared opinion of the Parliament, will tend to achieve economic security and social justice’; and all the new powers were to be exercisable ‘notwithstanding anything contained elsewhere in this Constitution’.

In the face of fierce Opposition backlash, at a time when Curtin was still navigating the perils of minority government, Labor agreed to a Constitutional Convention in which changes became more specified and restricted to a ‘temporary’ period of five years. There was also an attempt to do away with the necessity of a referendum all together, by getting State governments to voluntarily hand over the powers to the Commonwealth. Two ALP State governments passed legislation to that effect, but since the proposal essentially required unanimity to succeed, it was largely an exercise in allowing the Commonwealth Government to argue that it had at least tried to avoid a divisive and hyper politicised referendum in the middle of a war requiring the maintenance of national unity.

The referendum was also given the added sweetener of providing constitutional ‘guarantees’ of freedom of speech and freedom of religion. Pointing out that freedom of speech only appeared to need protection because of the government’s own censorship program, Menzies slapped down this attempt to introduce an abbreviated Bill of Rights. He emotively argued that:

‘this Constitution is our Constitution. We as a self-governing community made it. We are, without any subtraction, the makers of our own laws and the creators of our own executives. If free speech or a free press is to be destroyed, it can only be because we, through our Parliaments, have authorised or permitted it.

What an astonishing thing that a completely self-governing community should so distrust itself that it finds it necessary to write into its own Constitution an admonition that it is not to make a law abridging the freedom of speech or of the press!…

In the last resort it will be found that the only real assurance of freedom of speech or of the press will be a real spirit of freedom in the minds of the people. But if the people at any time became so carried away as to seek to destroy these freedoms, which are of our life blood, no pretty little form of words in the Constitution which they themselves made would prevent them from doing it’.

As for the 14 powers themselves, Menzies divided them into three categories: powers that the Commonwealth already had (e.g. repatriation and uniform gauges, powers which he opposed and believed were formulated with an intent to introduce socialism (employment, unemployment, and the production and distribution of goods), and powers he saw merit in, had the Australian people been asked to judge them on their individual merit (e.g. family allowance and national health). Notably Menzies would help to pass a referendum relating to these ‘social services’ powers in 1946.

As Opposition Leader, Menzies would throw himself whole-heartedly into the ‘No’ campaign, even winding up his long-running series of Friday night ‘Forgotten People’ broadcasts to concentrate on touring the nation to speak on the subject. After having divided into a myriad of smaller parties, the centre-right found considerable unity in the Australian Constitutional League/Union, a highly effective organisation set up to coordinate the ‘No’ campaign.

On the back of the ‘No’ victory, Menzies invited various centre-right bodies to a Unity Conference to be held in Canberra in two months after the vote had been held. ACL delegates from three States would be in attendance, as in a serendipitous coincidence, it would be exactly 14 organisations which came together to form the Liberal Party of Australia.

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.