| Entry type: Book | Call Number: 955 | Barcode: 31290035203090 |

-

Author

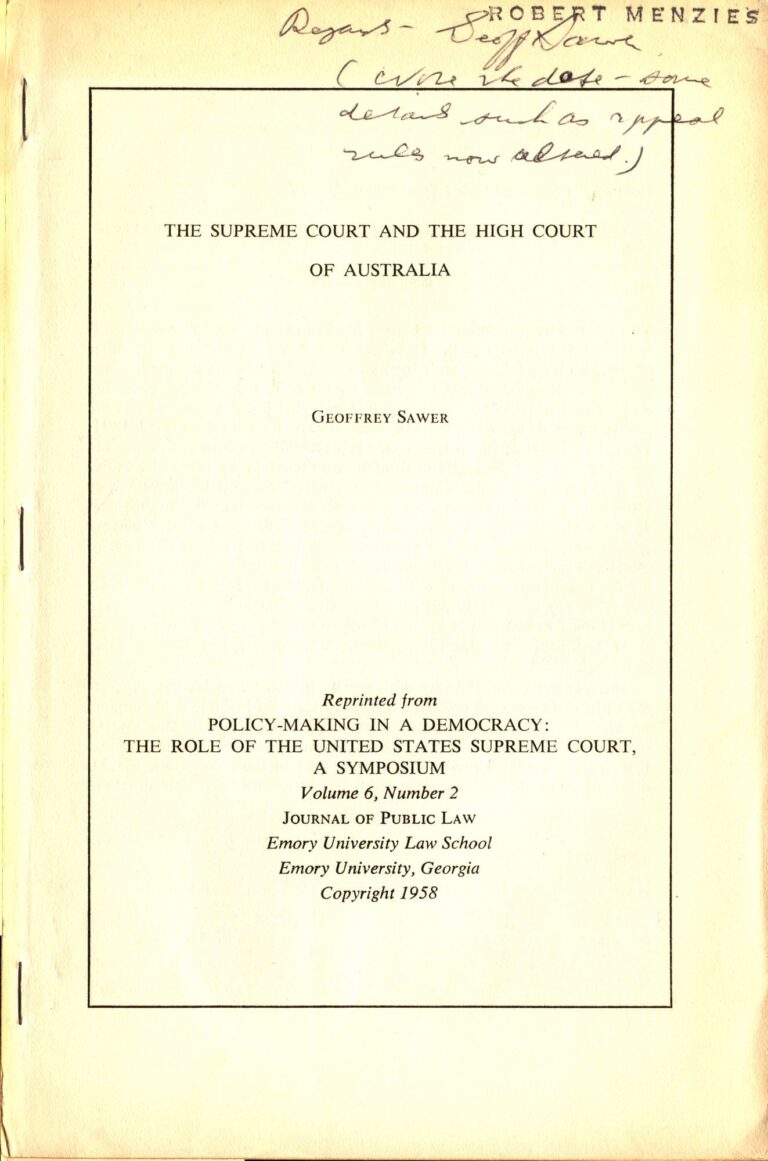

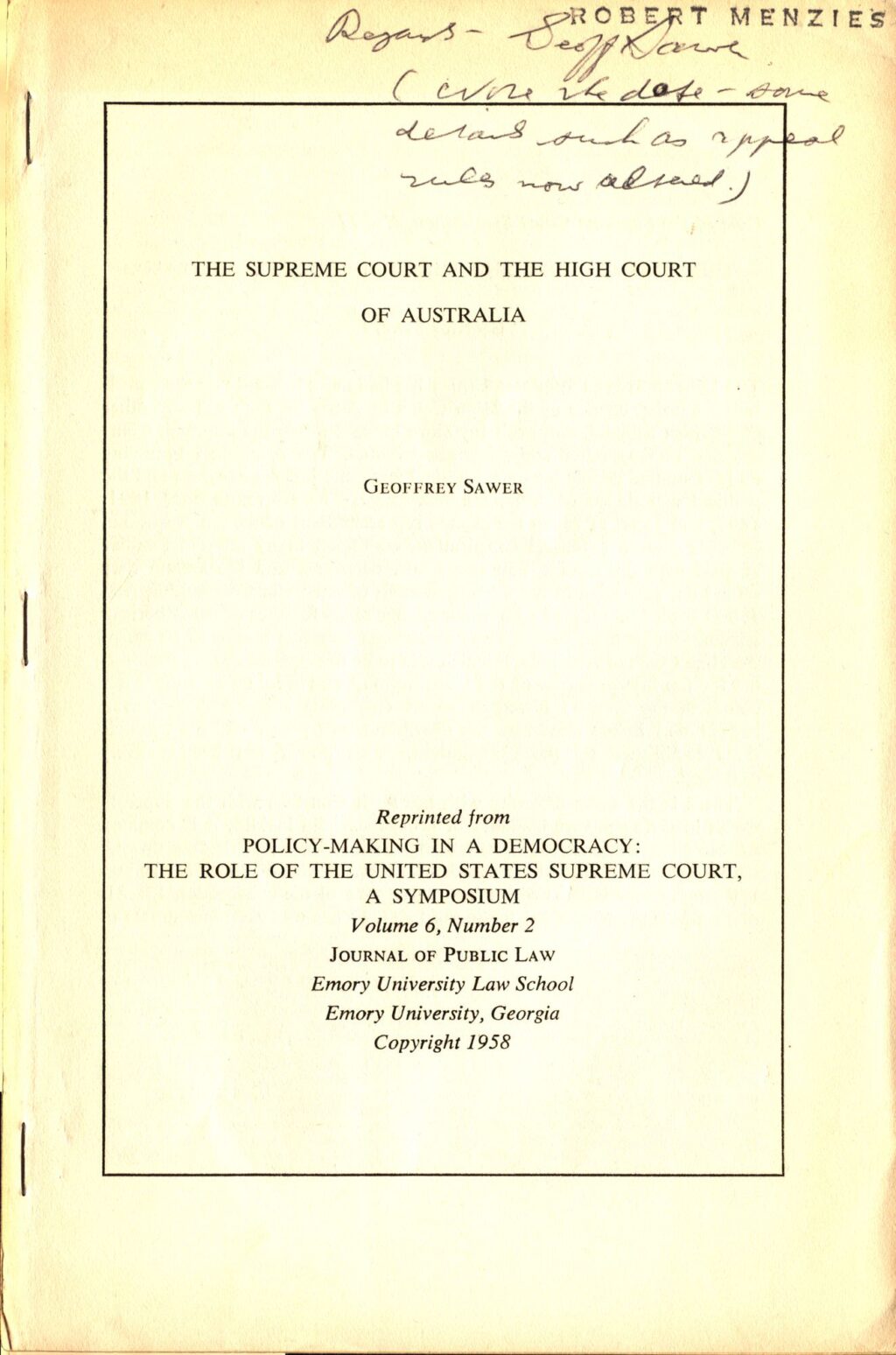

Sawer, Geoffrey

-

Publication Date

195[8]?

-

Place of Publication

Georgia

-

Book-plate

Yes

-

Edition

Reprint

-

Number of Pages

26

-

Publication Info

pamphlet

Copy specific notes

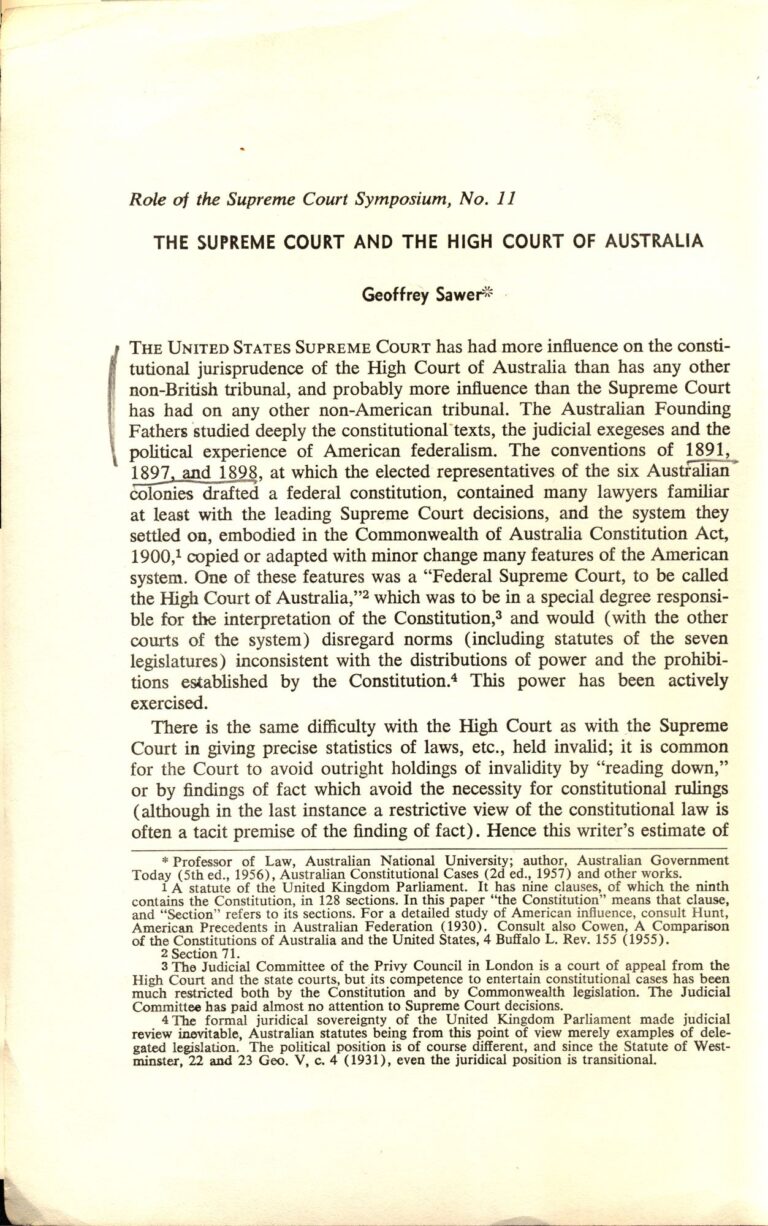

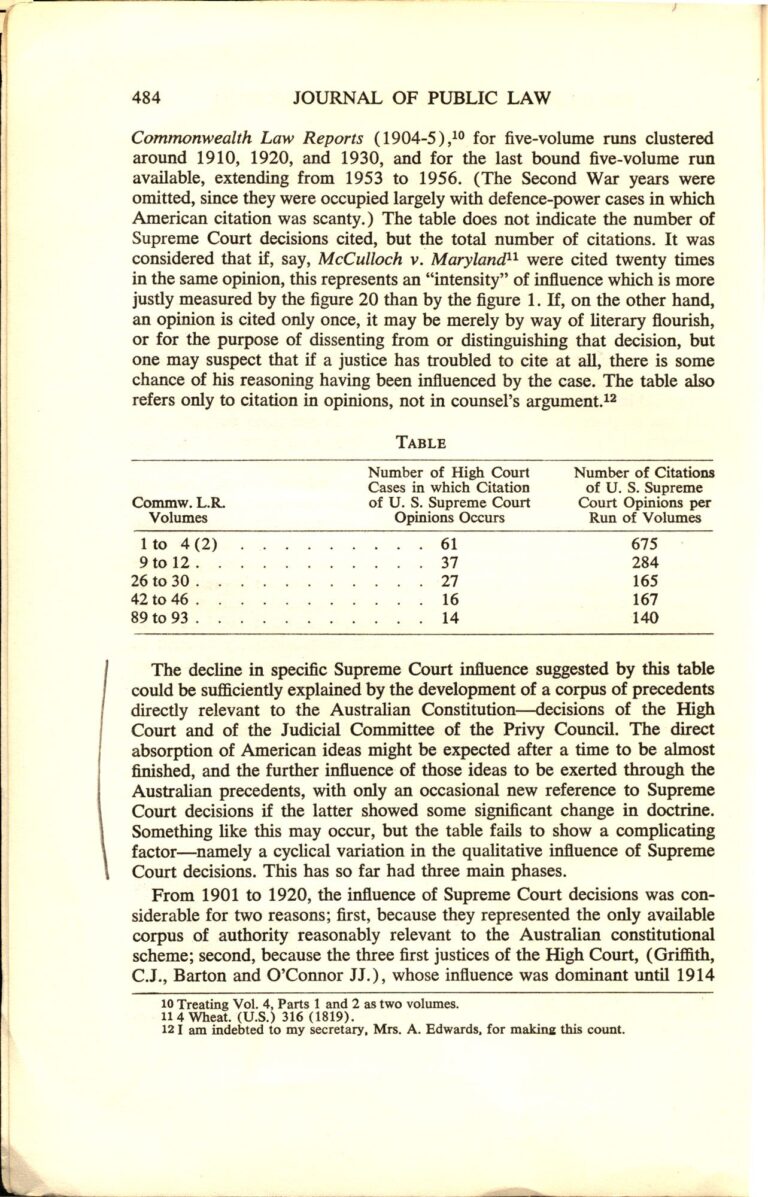

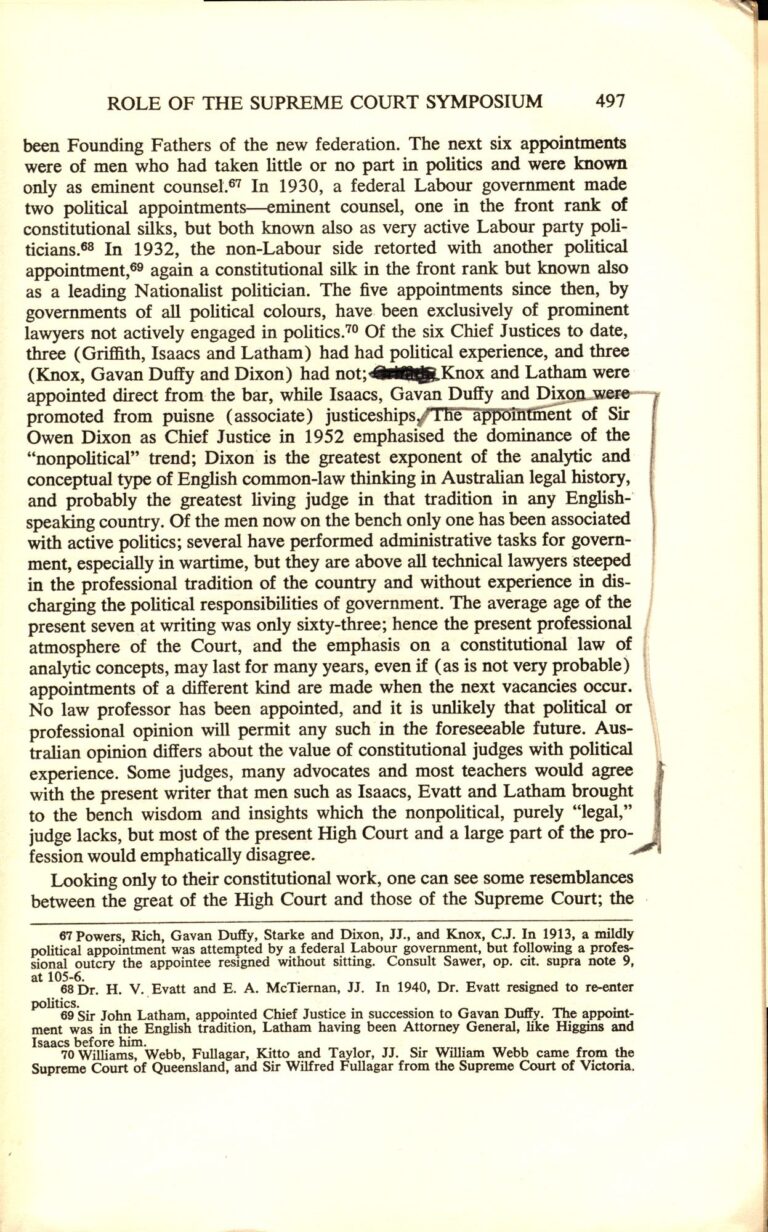

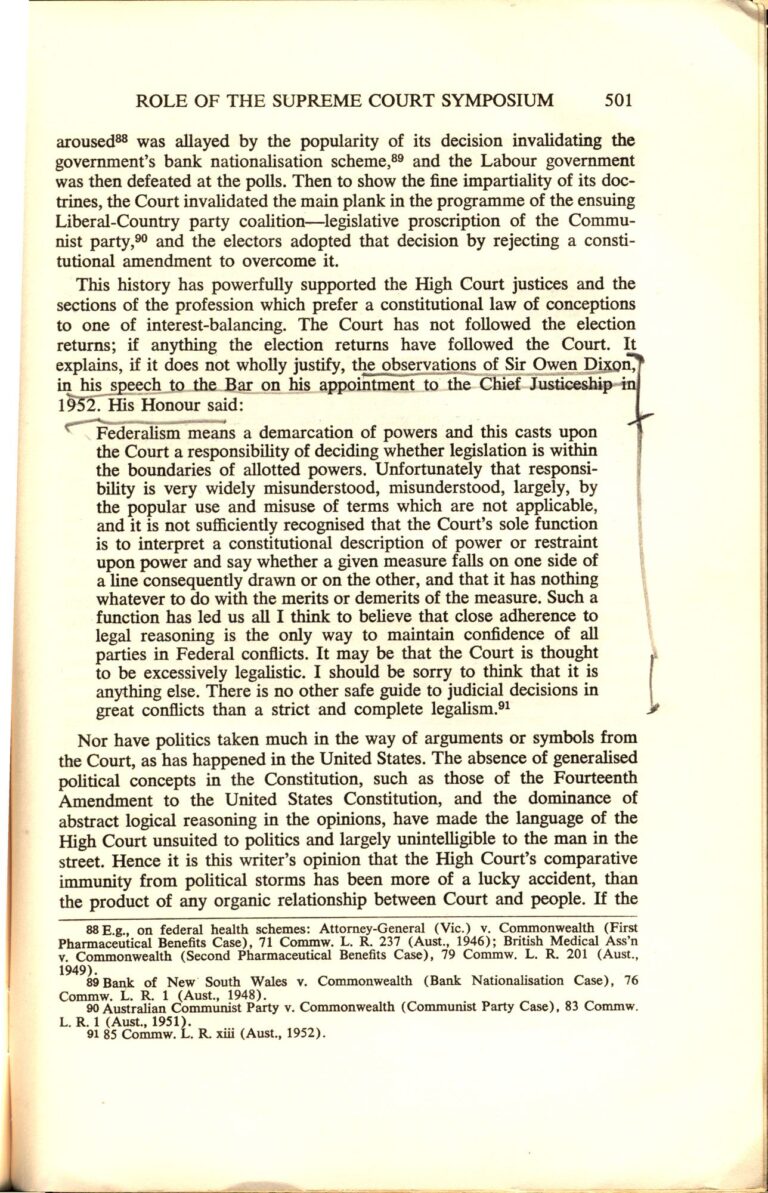

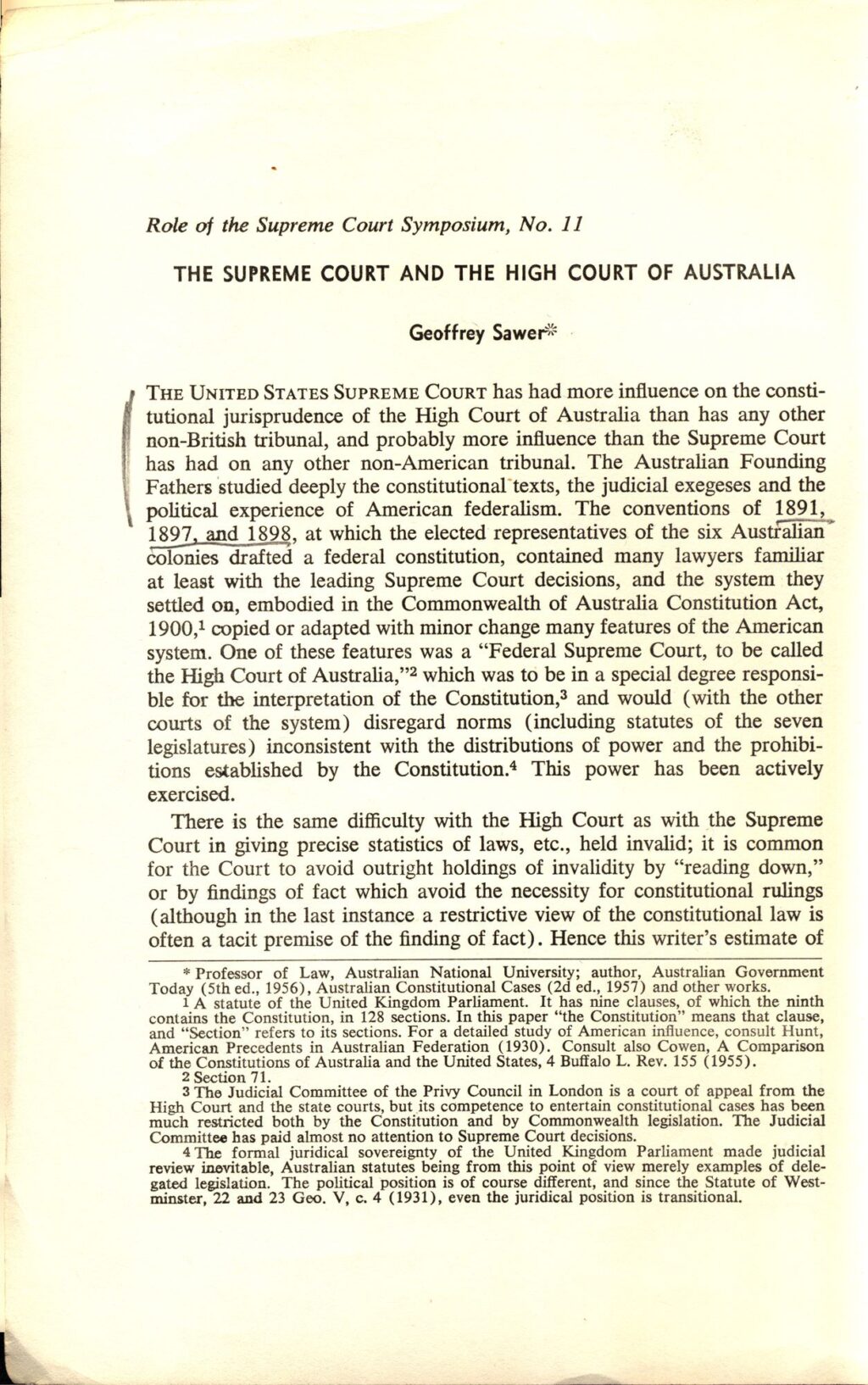

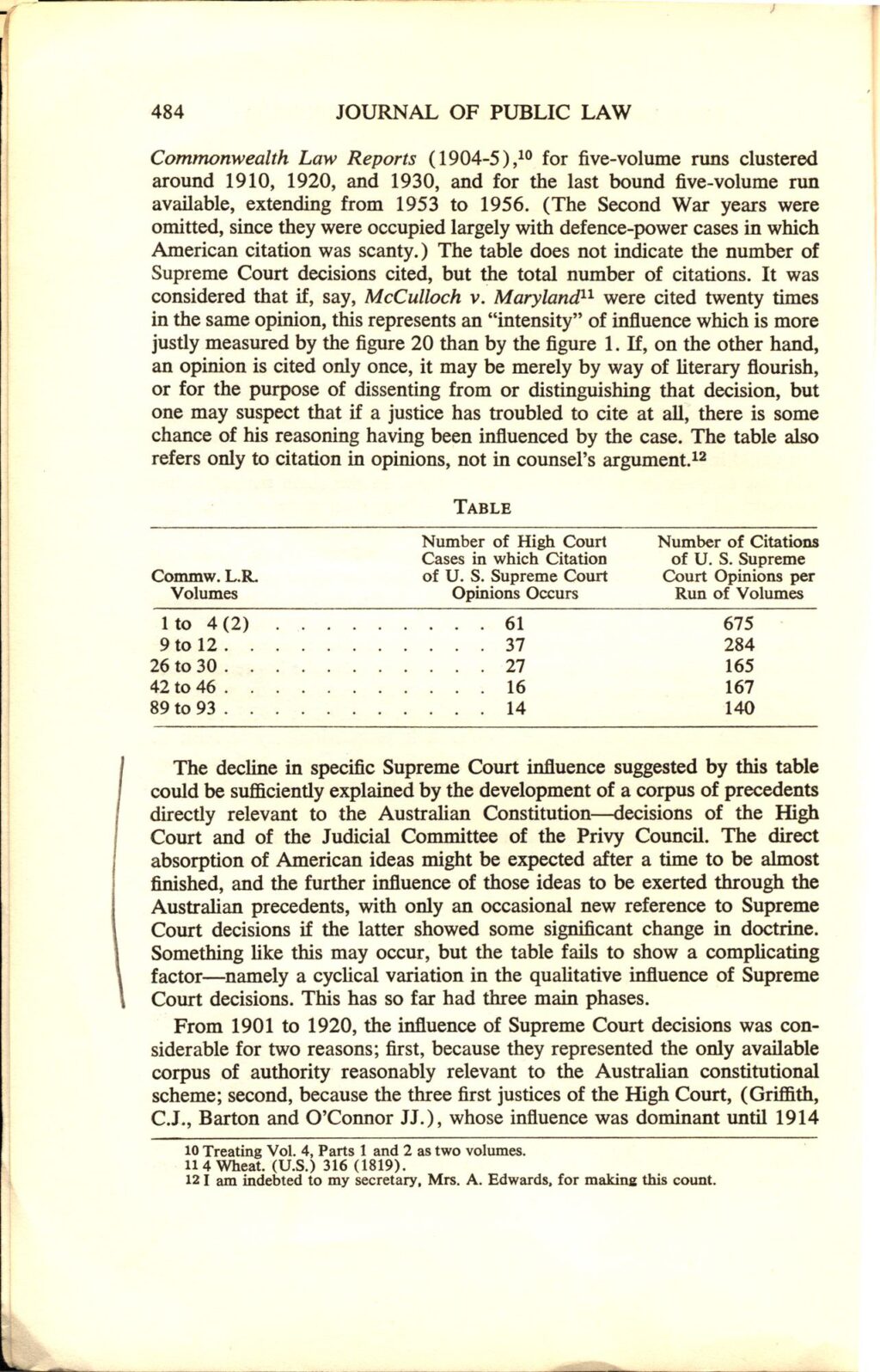

“Robert Menzies” stamp on front cover; inscribed in black ink: “Regards … (was the date – some details such as appeal rules now abscond.).” Text highlighted by Menzies includes: “The United States Supreme Court has had more influence on the constitutional jurisprudence of the High Court of Australia than has any other non-British Tribunal, and probably more influence on the Supreme Court has had on any other non-American tribunal. The Australian Founding Fathers studied deeply the constitutional texts, the judicial exegeses and the political experience of American federalism. The conventions of 1891, 1897, and 1898, at which the elected representatives of the six Australian colonies drafted a federal constitution, contained many lawyers familiar at least with the leading Supreme Court decisions, and the system they settled on, embodied in the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900, copied or adapted with minor change many features of the American System.” [p. 482]; “The decline in specific Supreme Court influence suggested by this table could be sufficiently explained by the development of a corpus of precedents directly relevant to the Australian Constitution – decisions of the High Court and of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. The Direct absorption of American ideas might be expected after a time to be almost finished, and the further influence of those ideas to be exerted through the Court decisions if the latter showed some significant change in doctrine. Something like this may occur, but the table fails to show a complicating factor – namely a cyclical variation in the qualitative influence of Supreme Court decisions. This has so far had three main phases.” [p. 484]; “The appointment of Sir Owen Dixon as Chief Justice in 1952 emphasised the dominance of the “nonpolitical” trend; Dixon is the greatest exponent of the analytic and conceptual of English common-law thinking in Australian legal history, and probably the greatest living judge in that tradition in any English-speaking country. Of the men now on the bench only one has been associated with active politics; several have performed administrative tasks for government, especially in wartime, but they are above all technical lawyers steeped in the professional tradition of the country and without experience in discharging the political responsibilities of government. The average age of the present seven at writing was only sixty three; hence the present professional atmosphere of the Court, and the emphasis on a constitutional law of analytic concepts, may last for many years, even if (as is not very probable) appointments of a different kind are made when the next vacancies occur. No law professor has been appointed, and it unlikely that political or professional opinion will permit any such in the foreseeable future. Australian opinion differs about the value of constitutional judges with political experience. Some judges, many advocates and most teachers would agree with the present writer that men such as Isaacs, Evatt and Latham brought to the bench wisdom and insights which the nonpolitical, purely “legal” judge lacks, but most of the present High Court and a large part of the profession would emphatically disagree.” [p. 497]; “the observations of Sir Owen Dixon, in his speech to the Bar on his appointment to the Chief Justiceship in 1952. His Honour said: “Federalism means a demarcation of powers and this casts upon the Court a responsibility of deciding whether legislation is within the boundaries of allotted power. Unfortunately that responsibility is widely misunderstood, misunderstood, largely, the popular use and misuse of terms which are not applicable, and it is not sufficiently recognised that the Court’s sole function is to interpret a constitutional description of power or restraint upon power and say whether a given measure falls on one side of a line consequently drawn or on the other, and that it has nothing whatever to do with the merits or demerits of the measure. Such a function had led us all I think to believe that close adherence to legal reasoning is the only way to maintain confidence of all parties in Federal conflicts. It may be that the Court is thought to be excessively legalistic. I should be sorry to think that it is anything else. There is no other safe guide to judicial decisions in great conflicts than a strict and complete legalism.” [p. 501]; p. 504 earmarked.

Related entries

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.