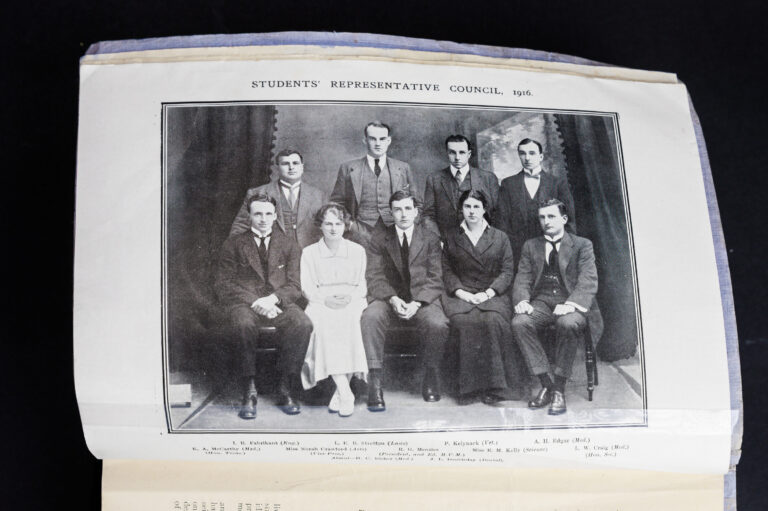

| Entry type: Book | Call Number: 1342 AX | Barcode: 31290030400980 |

-

Author

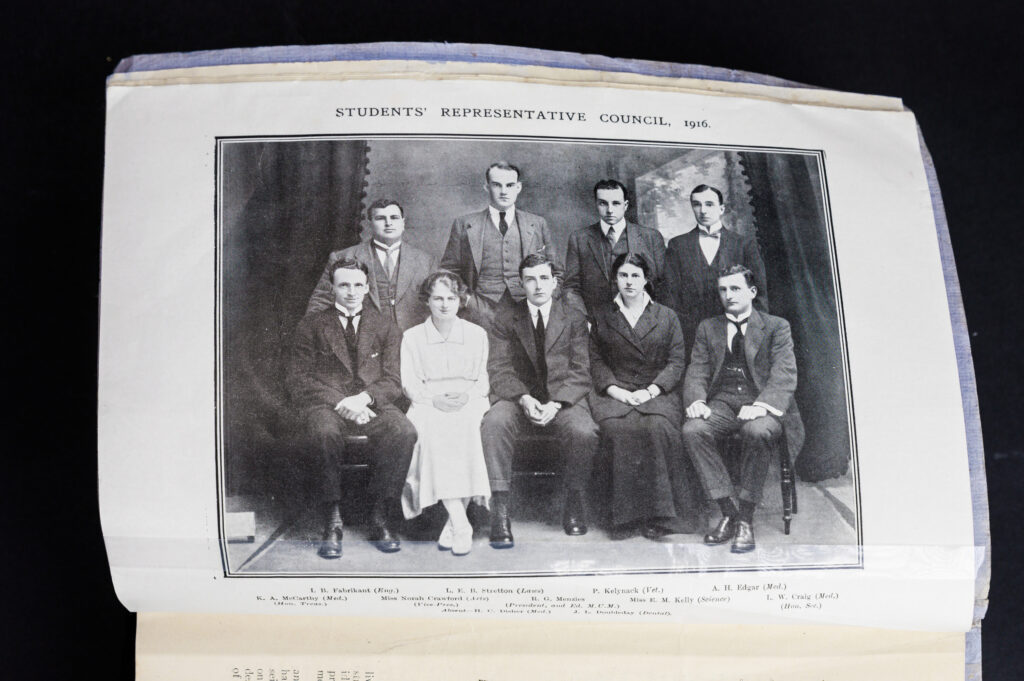

Melbourne University Students' Representative Council; Menzies, Robert Gordon (contr.)

-

Publication Date

1916

-

Place of Publication

Melbourne

-

Book-plate

Yes

-

Edition

First

-

Number of Pages

73 - 109

-

Publication Info

magazine

Copy specific notes

Includes poem by Robert Gordon Menzies “Frater Ave atque Vale” [p. 15]: “Hail and farewell, my brother – aye farewell! Darkness has come, to touch me on the cheek And whisper shuddering fears, and murm’ring tell The anguished fancies that I dare not speak. War – did it seem an awful thing to me? Did its dread music strike my soul? Or was it but the thundering of the sea, With a majestic cadence in its roll? Now, let the world pass by! For me has come Always a song, insistent in my ears – Bugles of Death, and wild barbaric drum, Fierce shouts of conflict – broken-hearted tears! Praise whoso list the pageantry of war: Hollow its triumphs when a nation weeps; Faded its laurels if, for evermore, Sorrow, enthroned, a sad dominion keeps! [/] Yet, let the word be Hail, and not Farewell! Let the bright sunlight pierce the cumbering cloud That dulls the vision, like some witch’s spell Drooping the head that else were high and proud! Proud with the ancient pride of blood and race, And duty done, and valour for the right: So have you gone, God’s glory on your face, And in your heart, calm courage for the fight.” Also includes article by Robert Gordon Menzies: “”The Shakespeare Tercentenary”: The Shakespeare Tercentenary.

The three-hundredth anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare finds the world still reading him, criticis-ing him, speculating upon him. A Chicago court has even recently decided that Shakespeare was Bacon; and this decision, colossal and farcical stupidity though it may be, is not without its significance. It is at least proof that in everything save appreciation of his unrivalled genius, opinion on Shakespeare is almost as diverse as the critics are numerous.

Three hundred years have passed, and through their almost impenetrable mists we see but little of the physi-cal man Shakespeare. A deer-stealing escapade or two on the lands of “lousy Lucy,” something of a romantic love, and then a glimpse at Elizabethan stage; very little more is vouchsafed to us. But not the passage of three thousand years can dim the splendours of the great series of dramatic achievements which commence possibly with “Love’s Labour Lost,” and end in the serene mastery of the “Tempest,” and a ”Winter’s Tale”. These are to us the spiritual man Shakespeare; more than that, they are the spiritual England in which he dwelt, and the priceless treasure of the England of centuries to come

For three hundred years Shakespeare has been scrutinised with the critic’s infallible eye; his political views have been delved for in many stray corners; most of the professions and many of the trades have claimed him for their own. But he survives all critics, bust as he baffles all description. To measure such a mountain by the literary foot rules that are too often applied to him can be nothing else but grotesque; possibly nobody would be more surprised than Shakespeare himself at some of the wonderful fabrics that have been built up on his obscurest sentences.

But of this we can be sure – that Shakespeare is the superbest genius of our literature – indefinable, constant-ly yielding fresh glories to him who seeks, speaking to all as if with “a gift of tongues,” and yet doing all this with such consummate ease and sureness that we forget the poet in the man and pass without an effort from the drama of the players to the human episodes of the world about us.

We respect and cherish our Milton, but we read our Shakespeare. It is surely not too much to say that for one who has listened to the sonorous and majestic story of the Almighty Power “Hurl’d headlong flaming from the ethereal sky,” there are a dozen to whom Shakespeare is something more than a name. The reason seems to lie in this – that Shakespeare was above all things a man speaking to men. All-comprehensive though his imag-ination was, he did not lose himself in its fogs. The world of men was his study, and just as one, gazing from a window upon a crowded street, might, looking deep enough, read many a tragedy and many comedy in the sea of faces, so does our Shakespeare, going to and fro in his sixteenth century world, make record of what he finds.

One doubts whether there was ever genius less consciously strove to win himself a lasting fame in the world of letters. Conceivably the dramatist might, had the subject been suggested, have said with Lowell – “It may be glorious to write

Thoughts that shall glad the two or three

High souls, like those far stars that come in sight

Once in a century.

But far better far it is to speak

One simple word, which now and then

Shall waken their free nature in the weak

And friendless sons of men.”

In short, Shakespeare wrote for the stage – for the many and not for the chosen few. And yet to-day, the few and the many vie with each other in doing to honour to him who has expressed the thoughts of all.

Shakespeare is our great practical poet. Dowden has well expressed this characteristic in these words: – “Dan-te – filled with keen political passion as he was – finds his [p.28] subjects of highest imaginative interest not in the life of Florence, and Pisa, and Verona, but in circles of Hell, and the mount of Purgatory, and the rose of beautiful spirits. Human love ceases to be adequate for the needs of his adult heart; the woman who was dearest to him ceases to be a woman, and is sublimed into the supernatural wisdom of theology. . . . But, with his ever present sense of truth, his realisation of fact, especially of that great fact, a moral order of the uni-verse, we cannot think of Shakespeare among the men of pleasure, scepticism, and irony. Neither can we pic-ture to ourselves an ascetic Shakespeare, suppressing his desire of knowledge, transforming his hearty sense of natural enjoyment into curiosities of mystic joy, exhaling his strength . . . in tender lamentations over the vanity of human love and human grief.”

Shakespeare may or may not merit the criticism levelled at him in Melbourne a few days ago, that “he was anti-democratic, and therefore a pollical menace.” His politics may be what they may be, Liberal or Conserva-tive, advanced or out-of-date; we in this century only know that in his pages we find passion and calmness, sorrow and joy, shadow and shine; a tune for our every mood: a great storehouse of sustenance for both mind and spirit, from which we may take and be satisfied.

R.G.M. [pp. 27 – 28]”; also includes contribution: “An Autumn Reverie” [pp. 58 – 59].

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.