| Entry type: Book | Call Number: 3777 | Barcode: 31290036144905 |

-

Author

Morgan, Charles

-

Publication Date

1951

-

Place of Publication

London

-

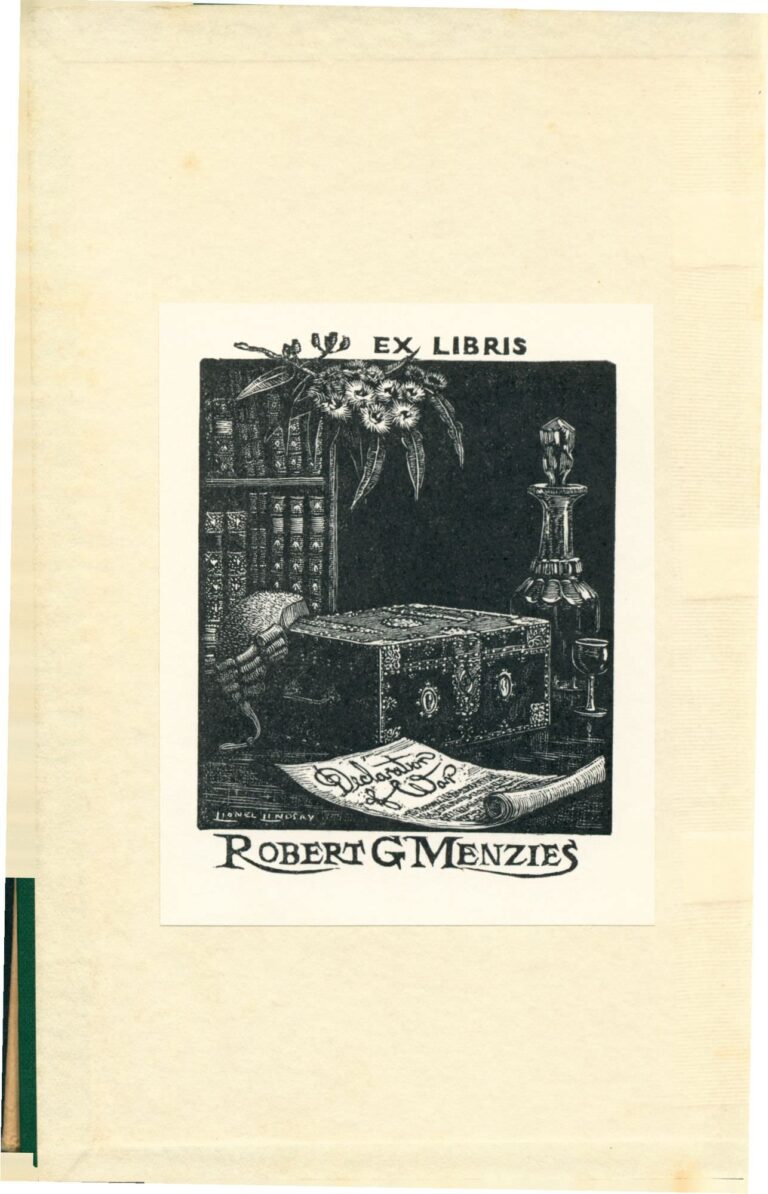

Book-plate

No

-

Summary

Inscription: 6 June 1951.

-

Edition

First

-

Number of Pages

252

-

Publication Info

hardcover

Copy specific notes

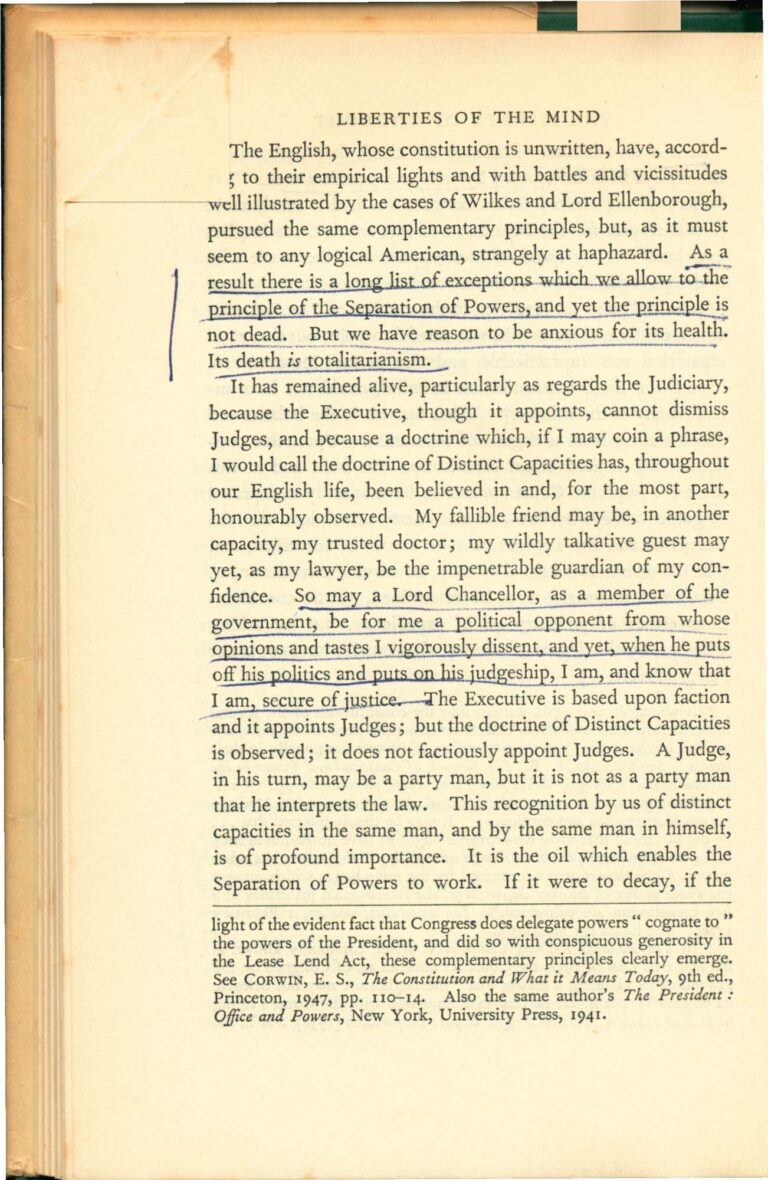

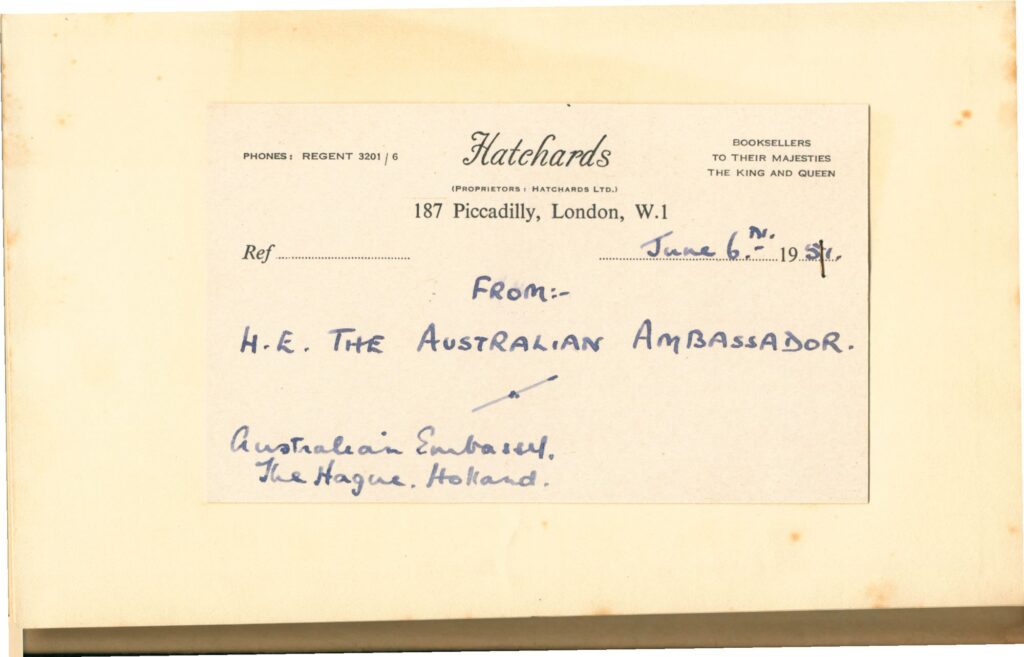

Bookplate inserted; card of Hatchards, Booksellers, 187 Piccadilly, London, W1, affixed to front endpaper and inscribed in blue ink: “June 6th, 1951. FROM H.E. THE AUSTRALIAN AMBASSADOR [Alfred Stirling]. Australian Embassy, The Hague. Holland.” Pp. 23, 25, 42, 66, 72, 221 earmarked; various passages of text underlined and highlights of text made in margin with pencil, including: “There is effect but no virtue in numbers. The earth was not the less round because everyone said that it was flat.” [p. 34]; “The second source of distress – its source in numerical thinking – is less understood, but even this has begun to declare itself. It is seen as inescapably true that, as votes increase in number, each vote diminishes in effect; the democratic currency is debased. An elector who weighs his choice and honestly tries to make it bear upon long-term policy is discouraged by knowing that his vote is cancellable by any one of millions of votes thoughtlessly cast. Even a vehement party-man or the most frivolous of self-seekers is aware of an extravagant contrast between the intensely personal quality of his needs or his hopes or his hatred and his electoral resemblance to a grain of sand on a gusty day. By having been pressed to an extreme, the doctrine of numbers has become an incubus of which the burden is felt even by the least discerning. Events external to the English-speaking peoples have brought the numerical development of their democracies into the field of criticism. Abroad, they have seen fully exemplified the old Aristotelean teaching of that cycle of human affairs in which extreme democracy leads to tyranny as certainly as one season follows another. In England, where this has already been made possible, the destructive cycle is not yet complete, but it is far advanced. Every constitutional barrier against tyranny has been removed. If an effective Second Chamber is not re-created, the Executive has to take but one step to dictatorship. This is beginning to be understood. A reconstructive measure of constitutional and electoral reform is a prime necessity and not so far out of reach as it was. [Everything, including democracy, is destroyed by its own extremes: personal rule by absolutism; oligarchy, or bureaucracy, by closeness, rigidity and centralization; plutocracy by avarice;] democracy by a watering of it its only valid currency of self-discipline and self-respect.” [pp. 41 – 42]; “The damage is done by averaging and habit. No form of censorship is a remedy for it. If the young went to films rarely and selectively there would be little harm, but there is bitter and destructive harm in their going – and, indeed, in anyone’s going – trice or three times a week to a programme selected for them. This not chiefly for the reason commonly given that they may learn gangsterism at this source or that when virtue triumphs on the screen it so often does so for the wrong reasons and is crowned with valueless rewards, but because film-going is habitual acceptance of ready-made imagining, designed to require a minimum effort of the receiver. No kind of fiction so consistently demands so little of its audience. The evil of its regular use is much less in the corruptive energy of particular exhibitions of violence than in the films’ collective, habit-making power to satisfy imaginative hunger “out of a can” and so to discourage the secret, individual imagination from following its own quarry.” [p. 50]; [concerning the “inward corruption of liberty”] “A principal sign of it is a respect for uniformity. There are, Montesquieu says, certain ideas of uniformity “which infallibly appeal to little minds. They find in them a kind of perfection.”” [p. 66]; “Education and true leisure enable men to exercise judgement; propaganda and mass-entertainment persuade them to surrender it.” [p. 67]; “[Western nations must vindicate their own principle of freedom, and, together and severally, set their house in order. For that purpose, not only may they have to resist new attempts to undermine their fortress, they may have by great measures of alliance abroad and of repeal and codification at home, to undo harm already done.] What is the final and unmistakable signal of that necessity? Montesquieu’s answer is clear: the concentration of powers in one set of hands. Personal liberty cannot survive without constitutional liberty, and for Montesquieu constitutional liberty rests upon the doctrine of his which is called the Separation of Powers.” [pp. 68 – 69]; [quoting G. M. Trevelyan’s criticism of Montesquieu] “The English in those days”, he said, “were better politicians than political theorists. They permitted the French philosopher, Montesquieu, to report to the world in his Esprit des lois that the secret of British freedom was the separation of executive and legislative, whereas the opposite was much nearer the truth”” [p. 70]; “I cannot help thinking that Montesquieu would have been better understood if his ruling doctrine had been called, not the Separation of Powers, but the Balance of Powers. “To prevent the abuse of power”, he says, “it is necessary that, by the disposition of things, power check power . . . il faut que, par la disposition des choses, le pouvoir arrête le pouvoir.” That, and not separation pedantically insisted upon, is the heart of his teaching. It is as an advocate of balance and check that Montesquieu has always been interpreted by wise and practical men.” [pp. 70 – 71]; “[The English, whose constitution is unwritten, have, according to their empirical lights and with battles and vicissitudes well illustrated by the cases of Wilkes and Lord Ellenborough, pursued the same complementary principles, but, as it must seem to any logical American, strangely at haphazard.] As a result there is a long list of exceptions which we allow to the principle of the Separation of Powers, and yet the principle is not dead. But we have reason to be anxious for its health. Its death is totalitarianism.” [p. 72]; [footnote related to sentence: “The incorporation of the Courts is of little avail if executive regulations have the force of law are so many”] “The Lord Chief Justice, giving judgement in Harding v. Price, said that “in these days, when offences were multiplied by regulations and orders to an extent which made it difficult for the most law-abiding subjects to avoid offending against the law, it was more important than ever to adhere to the principle (see Brend v. Woof, [1946], T.L.R. 462, p. 463) that, unless a statue clearly ruled out mens rea as a constituent part of a crime, the Court should not find a man guilty of an offence against the criminal law unless he had a guilty mind”. [p.73]; [concerning a fighter-pilot who dined with Morgan] “His point was this. He felt that everyone in the modern would – everyone, soldier, priest, scholar, tradesman or housemaid – was potentially, whether he knew it or not, either a Communist or a Nazi. “Potentially,” he insisted. “As yet, I’m neither myself. But I know which way I’d go if I had to choose. And that’s the question I ask myself about other people: which way would they go if they had to choose? Which side are they on?” [/] I said: “Are they necessarily on either side?” He answered: “Yes, I think they are, inside themselves. It think they must be. The world being what it is, a man can’t remain an indifferent.” That was the word I challenged. It seemed to me false to suggest that the whole area of opinion lying between the two opposed totalitarian polities was indifferent, neutral, colourless, waiting only to drift helplessly into one or other of the warring armies […] Many in Europe feel as he did. The choice has been thrust upon them. I still believe that, in the long view of history, he and they will be seen to have been wrong. I think that it is in the destiny of the English-speaking peoples and, ultimately, after many vicissitudes, of a recovered France, to prove them wrong. But the other alternative remains. The question may not yet be: “To which Authoritarianism shall we submit?” Not yet: “To which slave-master shall we surrender ourselves?” But already and urgently the question is: “Shall we be bond or free?” [pp. 84 -85]; “The greatest tribute that a writer earns from us is not that we keep our eyes fast upon his page, forgetting all else; but that sometimes, without knowing that we have ceased to read, we allow his book to rest, and look out over and beyond it with newly opened eyes, discovering all else.” [p. 95]; “from the point of view of the community, what is important in an artist is his impregnating-power, and that, from the point of view of an artist, what is important in the community is its power to be impregnated and to re-present his vision in an eternal vitality and freshness.” [p. 97]; [concerning the subjects of poetry and poems] “The fertilizing power is not the subject, but the aesthetic passion which the author pours into it; and this aesthetic passion is expressed not in subject alone or in treatment alone but in a harmony between them. Therefore we are not to say, except at the peril of an ultimate sterility: “This subject is admissible, that subject is barred,” or: “This treatment is admirable, that treatment is ruled out,” and this is precisely what the authoritarians of all ages do say.” [pp. 97 – 98]; [quoting verse of William Watson] “Great Heaven! When these with clamour shrill [/] Drift out to Lethe’s harbour bar [/] A verse of Lovelace shall be still [/] As vivid as a pulsing star.” [p. 99]; “The excellence of every art”, said Keats, “is -” What a wonderful beginning of a sentence! If the page of Keat’s manuscript had ended there and the next page had been lost, the world would have been breathless to know how the sentence continued. “The excellence of every art”, said Keats, “is-” and he did not say that it was in its subject or treatment, still less that it was in its social passion or its adherence to any ethical system of in its contemporaneousness. “The excellency of every art”, said Keats, “is its intensity.” And what did he mean by that? Fortunately he tells us. “Capable”, he continues, “of making all disagreeables evaporate from their being in close relationship with Beauty and Truth.” Do not misunderstand him. By “disagreeables” he not mean things that are unpleasant to us; he means those things which do not agree together, which clash in our immediate experience, but which harmonize when seen in the aspect of eternity.” [p. 100]; “We are wilful and enchanted children, by the grace of God […] He whom we love and remember is not he who thrusts upon us his own dusty chart of the Supreme Reality, scored over with his arguments, prejudices and opinions; nor he who will draw a map of heaven on the blackboard and chastise us with scorpions if we will not fall down and worship it; but he who will pull the curtain away from away from the classroom window and let us see our heaven with our own eyes. And this enablement of mankind, I take to be the function of true education, for the very word means a leading-out, and to lead out the spirt of man, through the wise, liberating self-discipline of learning and wonder, has been the glory of great teachers and of great Universities since civilization began to flower.” [p. 102]; “Nothing is so power in the company of men of divided mind as the influence of a whole man, selfless and dedicated.” [p. 220]; [concerning the opinion of a humanist in decision making for an industrial company] “In fact, industry does not work in a vacuum, but in a political and social atmosphere. It can no more insulate itself from the modern world, and every mind in industry fit to be called a mind is occupying itself more and more with a complex series of external and internal relationships and is trying to discern the values by which these relationships ought to be governed.” [p. 220]; “Men seek the counsel of judges on subjects unconnected with law, and in England the people will trust a judge to override their own prejudices where they will trust no one else on earth. Whenever the Executive is in doubt of an issue, and public opinion is so hot and confused that no decision by experts will quiet it, a judge of the High Court is asked to conduct an inquiry, and controversy is hushed. Why? As a man, a judge is as weak, vicious or fallible as other men are, but, as judge, there is an absolutism in him, a sacred truth, to deny which would be, for him, the impossible because the unimagined sin. It is not he that is just, but that justice of which he is the dedicated instrument.” [p. 224]. Note, in a speech in 1964 (The Universities – Some Queries. The Inaugural Wallace Wurth Memorial Lecture, 28th August, 1964) Menzies described this as a “remarkable book, and my favourite book”.

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.