| Entry type: Book | Call Number: 1847 | Barcode: 31290035256767 |

-

Author

Raleigh, Walter Alexander

-

Publication Date

1926

-

Place of Publication

London

-

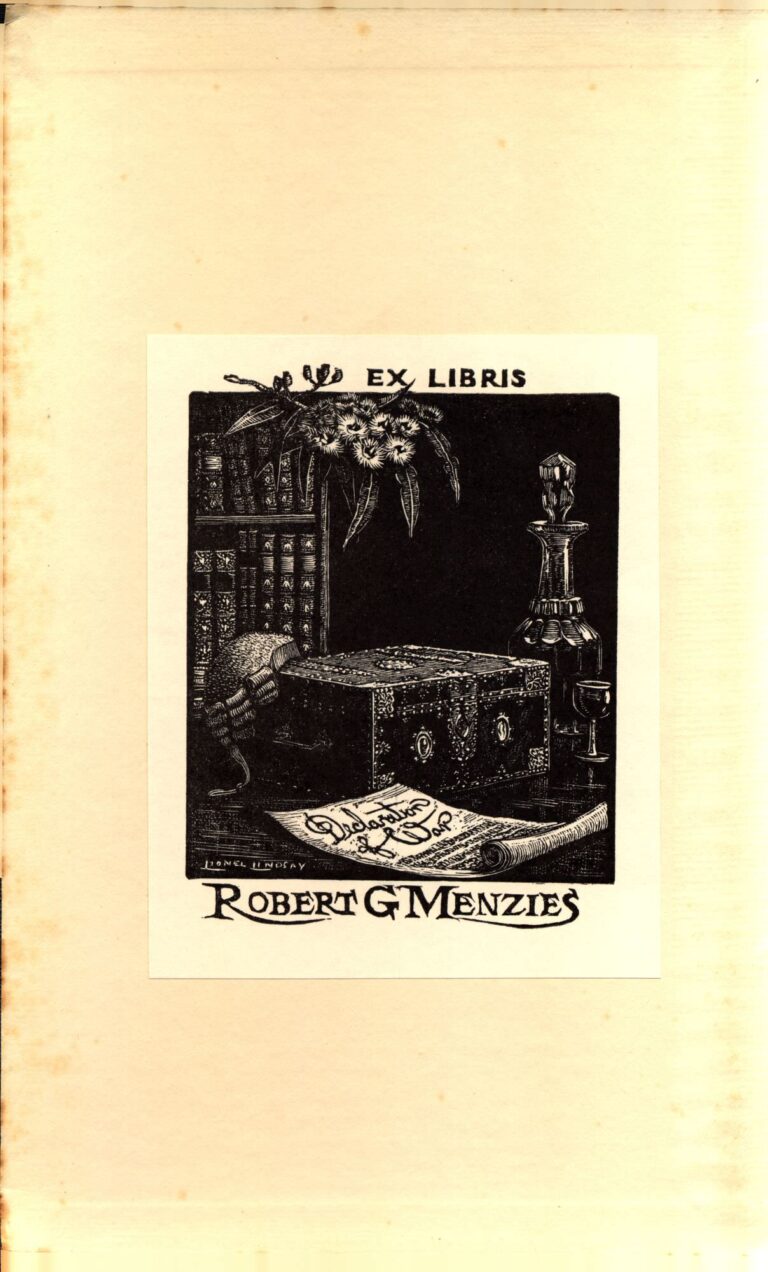

Book-plate

No

-

Summary

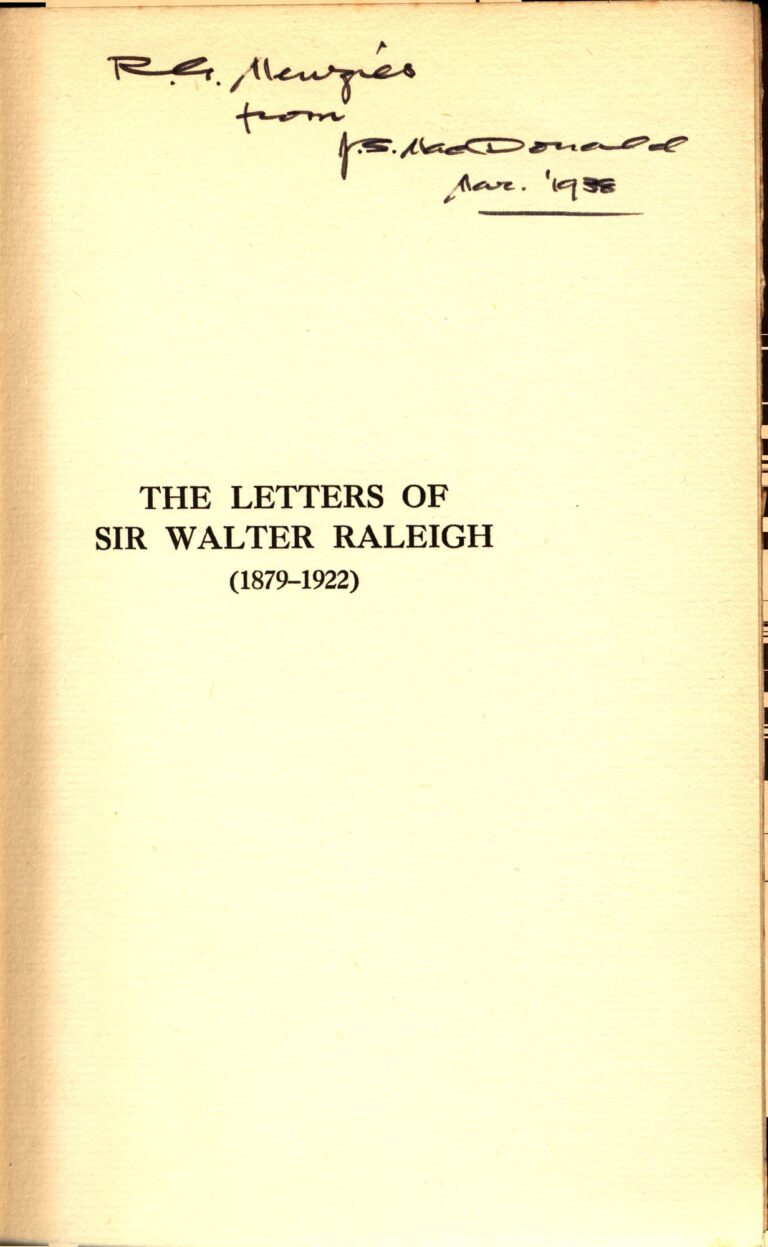

Inscription: March 1938.

-

Edition

Second edition (enlarged), first published February 1926

-

Number of Pages

272

-

Publication Info

hardcover

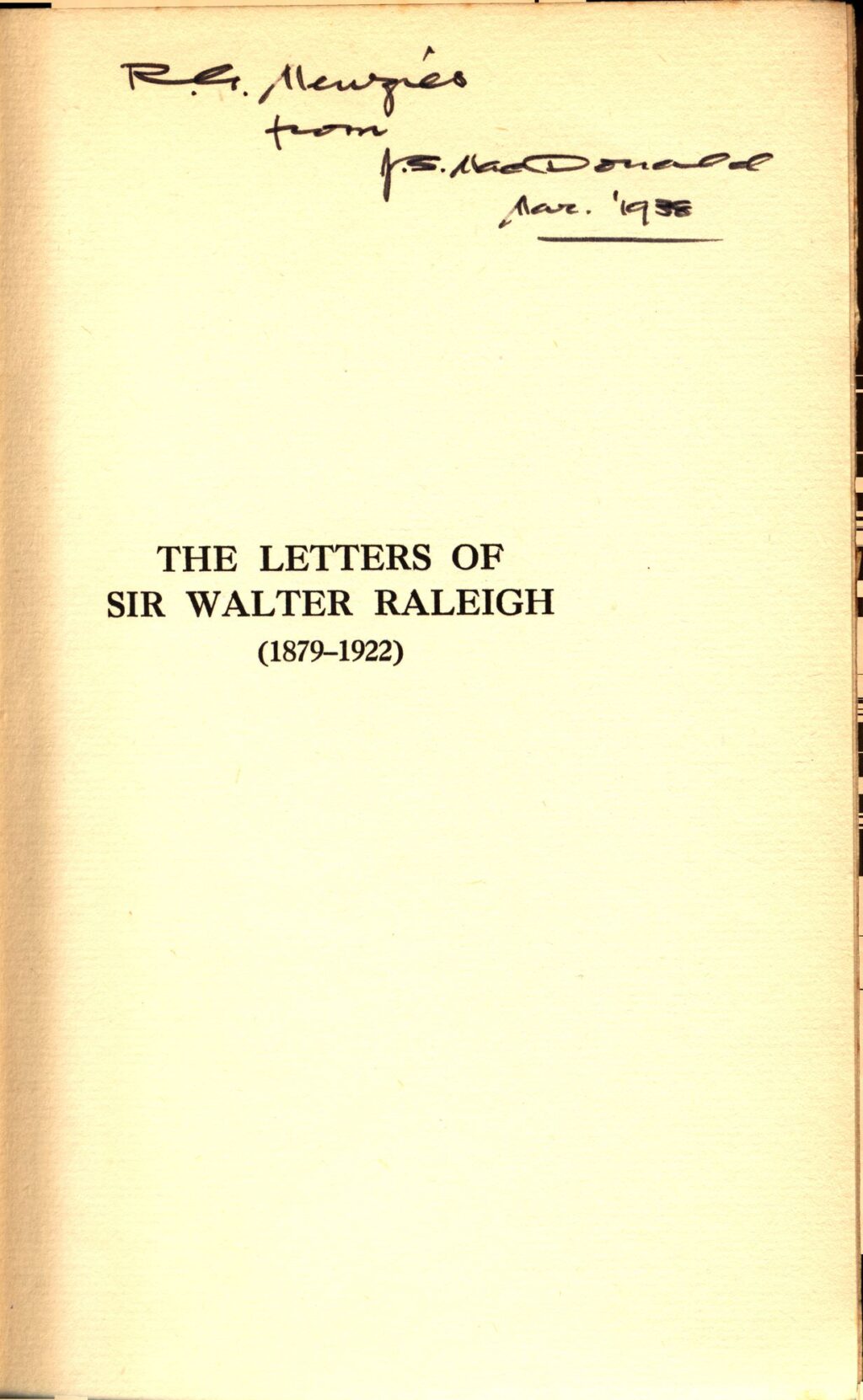

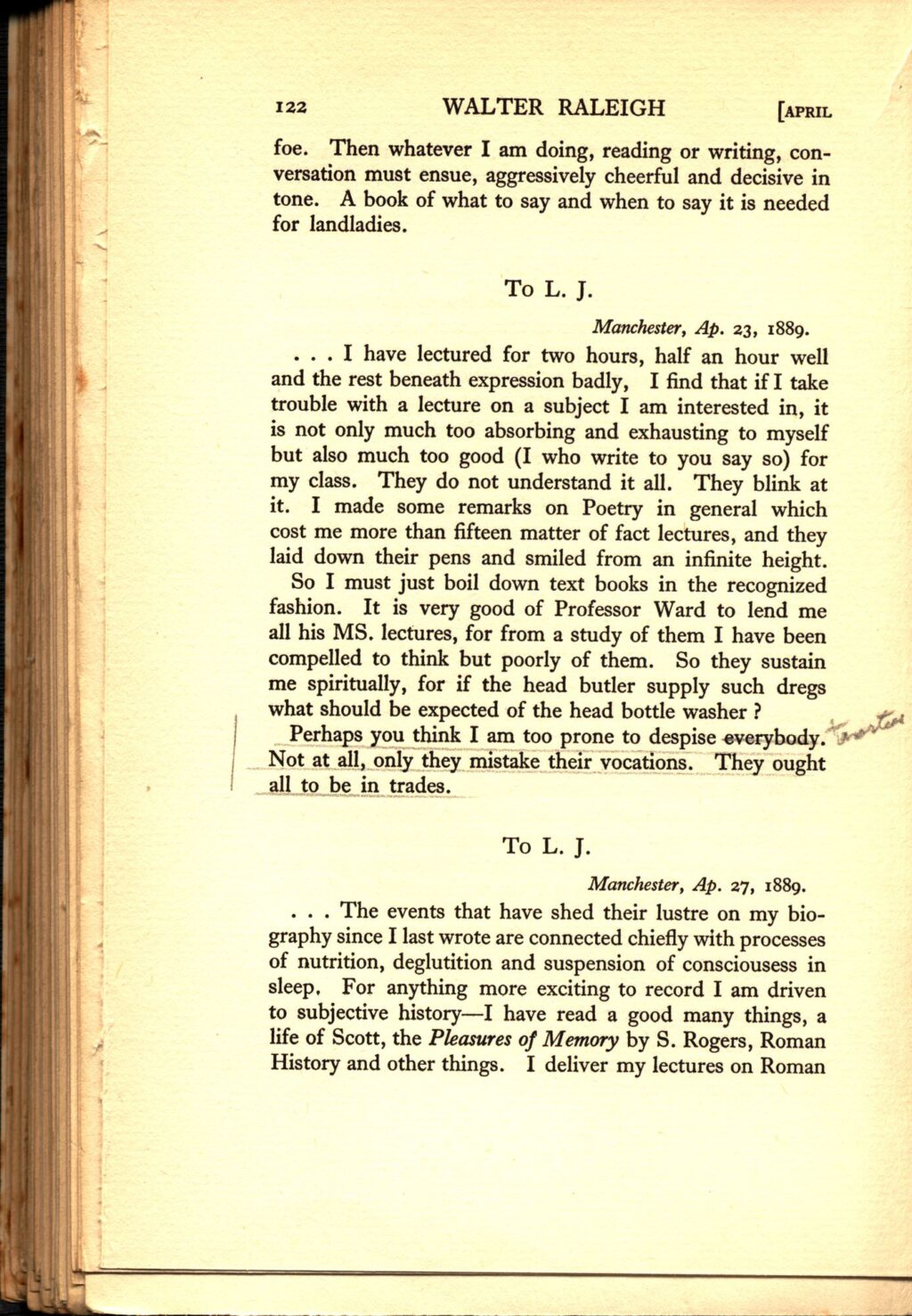

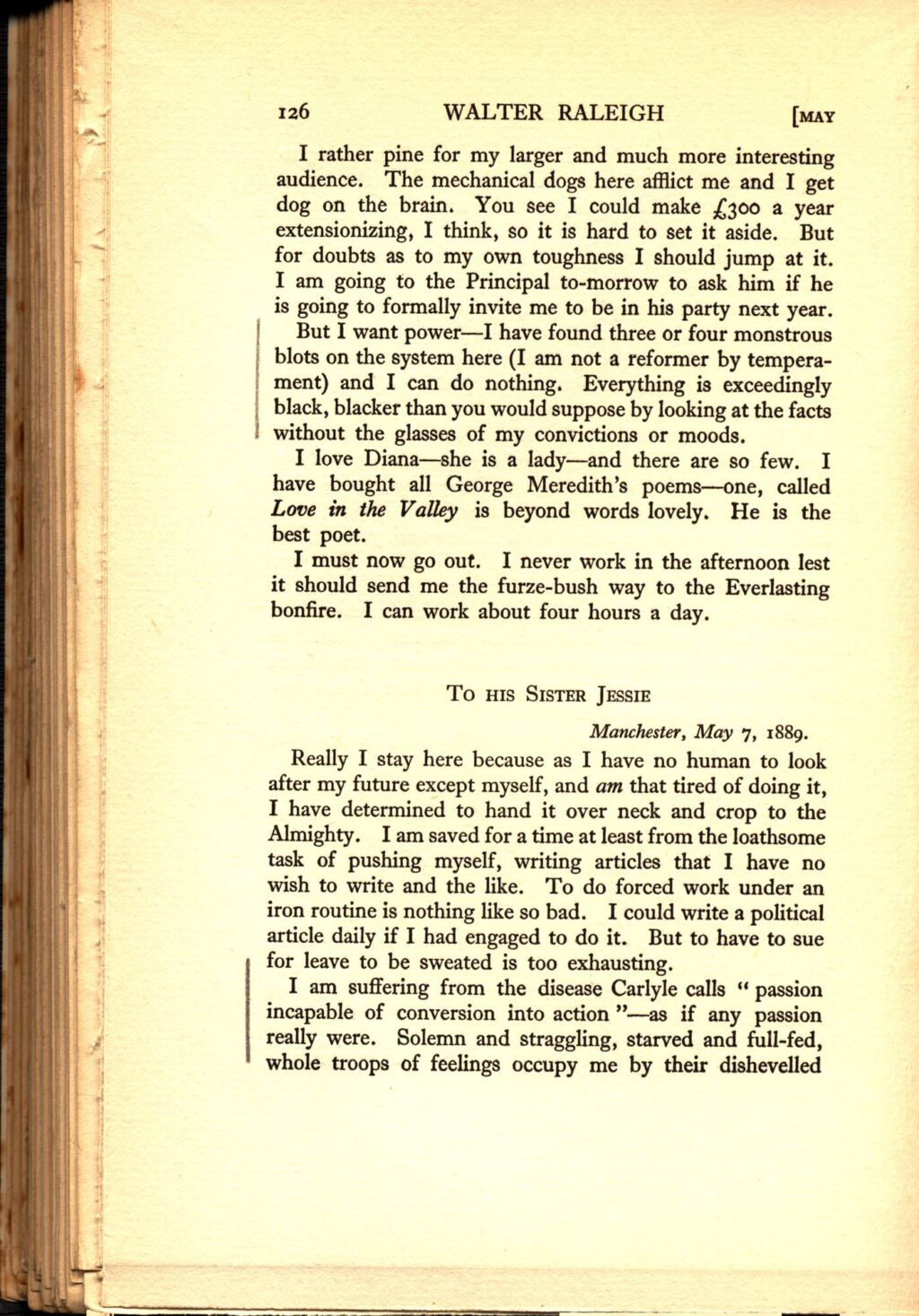

Copy specific notes

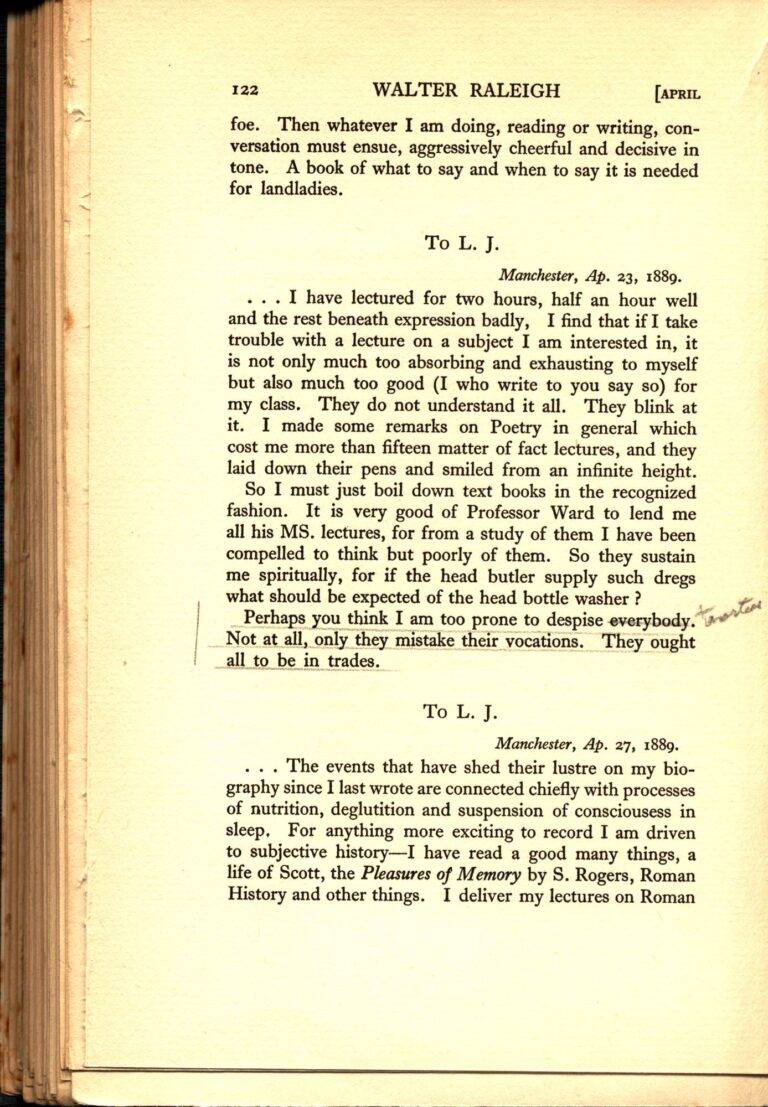

Bookplate inserted; inscribed in black ink on half title: “R.G. Menzies from J. S. MacDonald Mar. 1938.” Includes some underlining and notes in pencil, including: [p. 122, letter to L. J., Manchester, April 23, 1889] “Perhaps you think I am too prone to despise everybody [crossed out, indecipherable word in margin].”; [p. 126, letter to his sister Jessie, Manchester, April 29, 1889] “But I want power – I have found three or four monstrous blots on the system here (I am not a reformer by temperament) and I can do nothing. Everybody is exceedingly black, blacker than you would suppose by looking at the facts without the glasses of my convictions or moods.”; [p. 126, letter to his sister Jessie, Manchester, May 7, 1889] “I am suffering from the disease Carlyle calls “passion incapable of conversion into action” – as if any passion really were. Solemn and straggling, starved and full-fed, whole troops of feelings occupy me by their dishevelled [p. 127] procession through my mind, and in spite of their wailing and gibbering leave the will unawaked. I more than dread awaking it, for it would send them packing, and, having cleared the house, would contract its view and forget the world these visitants had returned to, and so set about some pitifully petty task. They do no make a happy household, they are all inexorable and some despotic; still at least I know which are phantoms and which have bodies – but my work suffers all the same.”; [p. 130, letter to Edmund Gosse, Manchester, May 16th, 1889] “I am a good deal puzzled – and the question is now a very practical one for me – to get a comfortable or permanent niche in the order of things in general for literary criticism. If it is simply tracing literary cause and effect, I do not see why a lover of literature ever should go on to it any more than I see why a lover of painting should study chemistry.”; [p. 142, letter to his sister Jessie, Liverpool, Jan, 1890] “Words could not convey an idea of the people here. Their hearts are fixed, O God, their hearts are fixed on the individual and temporal and accidental and trivial. If there is a judgment day it will have an element of grim humour. Puff – and the affairs that their eyes are large and their tongues noisy about, have shrivelled like tissue paper and gone off into smoke; and then comes the test question from the Searcher of hearts: “Look round you, and tell me if you see anything you are interested in.” And they will say “We protest, O God, that we see nothing [p. 143] we care for.” Now Heaven and Hell are for persons with ideas – a hell cannot be made out of the senses – so it is a curious problem what will become of them. But the state of mind just now, the state of mind! It is like some hideous nightmare – not humanity. Their criticisms on life are a fresh shock to me each time. . . .”; [p. 159, letter to D. S. MacCol, Liverpool, June 1, 1891] “I had a sort of drunken variant on the Influenza, with a week’s headache like a coffee mill, but that is gone. My son is well, as health goes in that strange period in his life, and so is his mother. We hope to be in London for a good part of July. I see with pleasure the great bases for eternity that you lay week by week in the Spectator. And pleasure is a rare extract from Art Criticism. I wish you would take an early occasion to explain what is the meaning of the word “literary” in the mouths of your contemporary critics. When the National Observer says “literary,” it always means, I conjecture, mawkish in sentiment, deficient in skill, wooden in presentment. Like the “Prometheus Bound” or “Macbeth” in short. Or if it means simply [p. 160] poaching on a foreign convention I wish it would unpuzzle me by explaining the precise nature and bounds of the rules under which a man with a pen works. I find, again, that a picture may be “poetic,” but it must not be “literary.” It seems to me that these gentlemen may be parroting merely. Instead of complaining of the absence of what ought to be there, they complain of the presence of what could not possibly be there (if they mean sequence in time, chiming of sense and sound, and other marks of the literary art) or else of what is common to all arts and ought to be there. Stevenson is a fine critic, but he is indirectly responsible for these bud-crowned noddies. What they try to do is build a complete artistic theory from the conditions proper to each particular art. When they allude to the more complex general conditions – associations, conditions, and the like – they do it with a delightful “of course,” as if everyone would understand religion, but the oblique muscles of the eye were stuff for a rare mind. And that is why the whole business seems to be futile except by way of elaborate treatise. I hope you are staying in London in July. I was at Manchester a day or two ago and saw Mr. and Mrs. Elton. We are trying to plan an Honours School in Literature. Tell me some things to put in, not being Anglo-Saxon, Comparative Grammar, or Moeso-Gothic.”

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.