Thomas Babington Macaulay, The History of England from the Accession of James the Second, 2 vols (1877)

Thomas Babington Macaulay was a nineteenth century politician and widely-read historian, known for espousing the ‘Whig interpretation of history’ in which the events of the past are viewed as a teleology of progress.

Born in Leicestershire in 1800, Macaulay’s father was a Presbyterian Minister who served as Governor of Sierra Leone and assisted William Wilberforce’s successful campaign to abolish slavery. The eldest of nine children, Thomas took an interest in history from a very young age, writing a ‘compendium of universal history’ at just 8 years old. He obtained a law degree from Trinity College Cambridge, but did not end up practicing. Instead, he emerged as a prominent writer, before entering Parliament in 1830.

Macaulay’s maiden speech called for the abolition of legal restrictions on Jews, and he quickly earned a reputation as an eloquent speaker during the debates over the Great Reform Act of 1832. Posted to an administrative position in India, Macaulay strove to improve education standards, ensure freedom of the press, and establish the legal equality of Indians and Europeans. Returning to England in 1838, he took up Cabinet positions as Secretary for War and Paymaster General.

However, Macaulay soon lost interest in politics, as he became caught up in the writing of his seminal History of England. Published in 1849, the book saw immediate and ‘unprecedented’ success, becoming one of the most widely read books of the age and for decades to come. The book is a triumphalist narrative of the circumstances leading up to the Glorious Revolution of 1688, in which reformers were viewed to have won Constitutional Monarchy – whereby the King would be bound to rule according to the supremacy of Parliament. The book would inspire generations of people to view Britain as a model of steady and inevitable progress, and a champion of liberal freedoms – a view which only really came into question with the onset of two world wars.

As was very typical of men of his era, Menzies read Macaulay intently, and The History of England seems to have had a significant impact on his worldview – both directly, and as a cornerstone of a culture which Menzies absorbed more broadly. The diary Menzies kept on his first visit to England in 1935 contains references to Macaulay’s work. Meanwhile, his Forgotten People essay on ‘The Achievements of Democracy’ quotes an extended extract from Macaulay to highlight how society had improved and was continuing to improve:

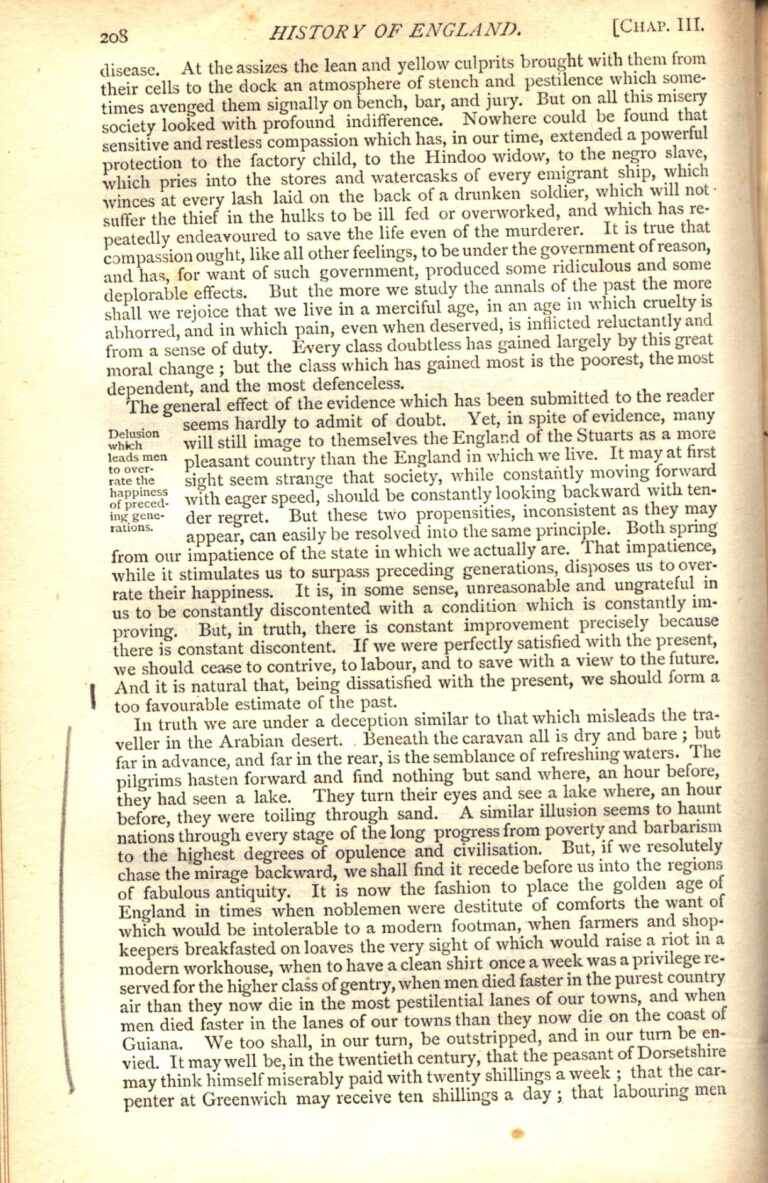

‘It is natural that, being dissatisfied with the present, we should form a too favourable estimate of the past.

In truth we are under a deception similar to that which misleads the traveller in the Arabian desert. Beneath the caravan all is dry and bare; but far in advance, and far in the rear, is the semblance of refreshing waters. The pilgrims hasten forward and find nothing but sand where, an hour before, they had seen a lake. They turn their eyes and see a lake where, an hour before, they were toiling through sand. A similar illusion seems to haunt nations through every stage of the long progress from poverty and barbarism to the highest degrees of opulence and civilisation. But, if we resolutely chase the mirage backward, we shall find it recede before us into the regions of fabulous antiquity. It is now the fashion to place the golden age of England in times when noblemen were destitute of comforts the want of which would be intolerable to a modern footman, when farmers and shopkeepers breakfasted on loaves the very sight of which would raise a riot in a modern workhouse, when to have a clean shirt once a week was a privilege reserved for the higher class of gentry, when men died faster in the purest country air than they now die in the most pestilential lanes of our towns, and when men died faster in the lanes of our towns than they now die on the coast of Guyana. We too shall, in our turn, be outstripped, and in our turn be envied. It may well be, in the twentieth century, that the peasant of Dorsetshire may think himself miserably paid with twenty shillings a week; that the carpenter at Greenwich may receive ten shillings a day; that labouring men may be as little used to dine without meat as they now are to eat rye bread; that sanitary police and medical discoveries may have added several more years to the average length of human life; that numerous comforts and luxuries which are now unknown, or confined to a few, may be within the reach of every diligent and thrifty working man. And yet it may then be the mode to assert that the increase of wealth and the progress of science have benefited the few at the expense of the many, and to talk of the reign of Queen Victoria as the time when England was truly merry England, when all classes were bound together by brotherly sympathy, when the rich did not grind the faces of the poor, and when the poor did not envy the splendour of the rich.’

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.