Henry Cockburn, Circuit Journeys (1888)

Lord Henry Cockburn was a Scottish lawyer, judge and literary figure who served as Solicitor-General for Scotland from 1830-34, and toured the country as a judge from 1837-1854.

Born in Midlothian in 1779, Cockburn was from an aristocratic Scottish family and his father, Archibald Cockburn, was a judge and ‘keen Tory’. Educated at the University of Edinburgh, Cockburn entered the ‘Faculty of Advocates’ in 1800, embarking on what would prove to be a highly successful legal career. His claim to fame was that he won the acquittal of Helen McDougal during the trial of the infamous Burke and Hare murders, in which 16 people were killed so that their bodies could be sold for dissection at anatomy lectures. Helen was Burke’s wife, who was suspected of assisting in the heinous business model.

Along with acting as a lawyer and judge, Cockburn was a talented author who wrote frequently for the Edinburgh Review. He would apply this skill at writing when keeping a diary of his time spent as a Circuit Judge, travelling around Scotland administering justice on behalf of Queen Victoria.

Published as Circuit Journeys, these diaries are a unique historical artefact which records the extent of Scottish poverty and associated crime in the 19th century, often contrasted with the wealthy upper-class world in which Cockburn otherwise lived. For example, Cockburn recorded the case of an eight-year-old boy in Glasgow who was physically compelled to sweep 38 chimneys without food or rest, dying at the end of the ordeal. In contrast to his father, Cockburn had some Whig sensitivities, and he took note of:

‘the full measure of the wretchedness of ill-housed poverty. We saw mud-hovels to-day, and beings with the outward forms of humanity within them, which I suspect the Esquimaux would shudder at. And this, as usual, close beside the great man’s gate.’

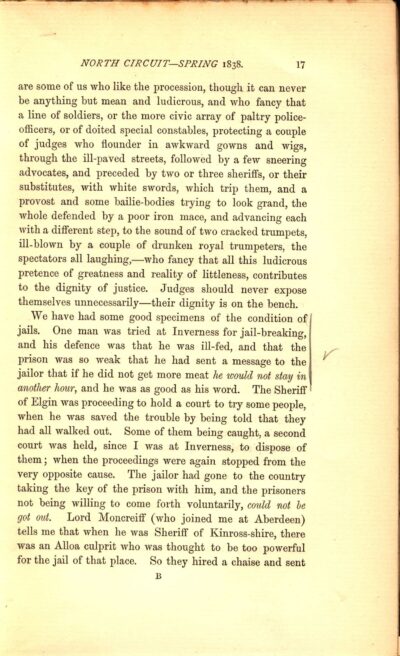

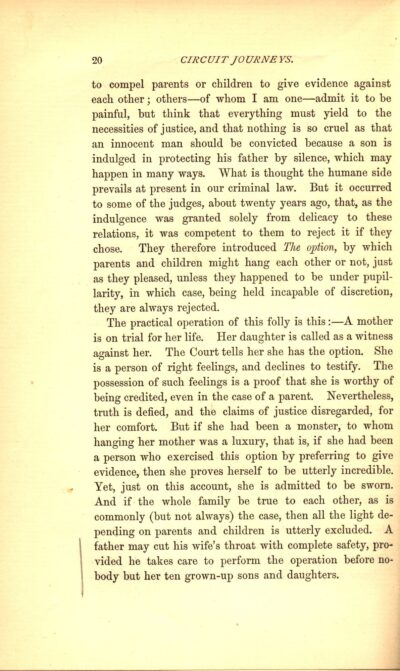

The laws themselves were often as harsh as the social conditions, as in the heyday of convict transportation, the book records how relatively minor offences saw poor Scots condemned to Australia. Cockburn seems to have almost been bored by the sheer quantity of ‘aggravated thefts, followed by seven years’ transportation, ad nauseam’. A stiffening of the laws saw even acts of bigamy produce a one-way ticket to the antipodes, while for harsher crimes a life sentence was an act of mercy.

Cockburn records people’s unique reactions to hearing the news that they were to be sent to the other side of the world. One Glasgow thief laconically replied ‘Ay! There’s a wind up for you’. Meanwhile a group of ladies prepared themselves to deliberately faint on hearing the news in an attempt to elicit sympathy, even making sure that they had someone standing behind to catch them, only to have the scheme fall apart because each of the acting incidents were so similar that the trend was quickly spotted.

Despite the dark tone of Circuit Journeys, it is easy to see why Menzies would want a copy of the book. Ultimately, it intermixes three of his greatest interests: Scotland, the Law, and Australian history – and he was not a man who wanted to see them purely through rose tinted glasses.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.