Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist: A Commentary on the Constitution of the United States (1904)

Alexander Hamilton was one of the ‘Founding Fathers’ of the United States of America.

Born in the West Indies in 1755 or 1757, Hamilton’s parents were unmarried and his father abandoned him at an early age. Consequently, he had to work from the age of 11 as a clerk for local merchants, showing ability and industry which saw him rise from bookkeeper to manager. Having earned some money and a reputation, he arrived in the mainland American Colonies in 1772 in the hope of receiving a formal education, and quickly found himself intwined in the political disturbances that would lead to the American Revolutionary War.

Hamilton publicly backed the Boston Tea Party, and began writing influential pamphlets supporting the Continental Congress. When conflict finally broke out, he joined the revolutionary army, demonstrating ‘conspicuous bravery’ that caught the attention of General George Washington. Employed as Washington’s personal aide-de-camp, he became the General’s right-hand man, and ultimately joined him in making the transition from military service to politics.

As a politician, Hamilton became the main force pushing for a strong central government, as opposed to a looser confederation of largely autonomous States that initially emerged from the war. The Federalist was written to advocate for a new American Constitution, which ultimately won adoption – but it was no sure thing, and protracted debates produced the American Bill of Rights which was designed to ensure that individuals were protected against the new powerful Federal Government the Constitution produced. Hamilton strongly argued against the proposal to add a Bill of Rights, insisting that ‘the constitution is itself in every rational sense, and to every useful purpose’ already a Bill of Rights.

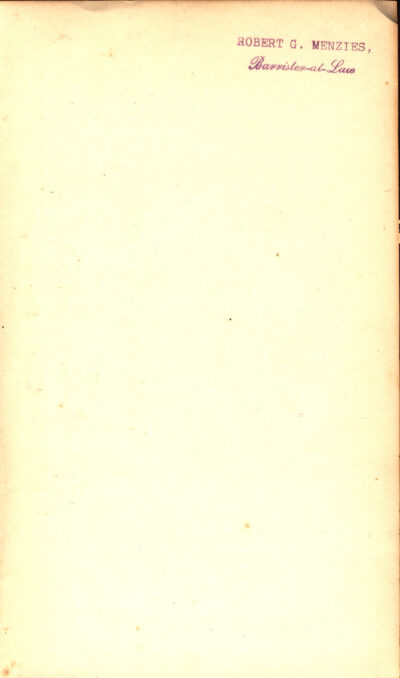

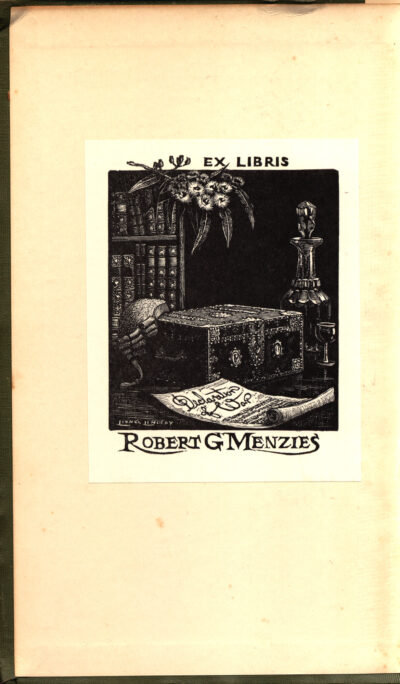

Robert Menzies likely bought his copy of The Federalist in the early 1920s when he was an up-and-coming constitutional lawyer, and he signed the book ‘Robert G. Menzies, Barrister-at-Law’. Menzies’s views on centralisation of the kind Hamilton advocated were complex. His victory in the landmark Engineers’ Case of 1920 was a major blow struck against the principles of federalism and in favour of a strong Commonwealth Government, though he likely accepted the case on the basis of the ‘cab rank’ rule and therefore its arguments and effects represented his legal rather than personal opinion on the matter.

Australian liberalism had long been a champion of State autonomy and subsidiarity (the idea that political decisions are best made at the most local level which is practicable), opposing Labor’s repeated attempts to enlarge the powers of the central government, and Menzies himself would lead the fight against several constitutional referenda during the 1940s. However, he did support the Social Services amendment and in office he would step into several fields that were traditionally the prerogative of the States, most notably education. After retirement, Menzies would even lecture in the United States on constitutional developments, and produce the book Central Power in the Australian Commonwealth.

One issue that Menzies certainly did agree with Hamilton on was opposing a Bill of Rights, which he felt was contrary to the organic evolutionary nature of the Common Law and of the British Constitution. The 1944 ‘Post-War Reconstruction and Democratic Rights referendum’ proposed to legally enshrine freedom of speech and freedom of religion, and Menzies would directly quote from The Federalist in opposing these points. During a radio broadcast on ‘Constitutional Guarantees’ delivered on 27 November 1942, Menzies said:

‘The great Alexander Hamilton opposed their inclusion [that of a Bill of Rights], using the same argument which I have already glanced at, that self-government ensures a better recognition of popular rights than carefully written guarantees. He pointed out that – “Bills of Rights are in their origin stipulations between kings and subjects, abridgements of prerogative in favour of privilege, reservations of rights not surrendered to the prince.” That was a very just observation.’

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.