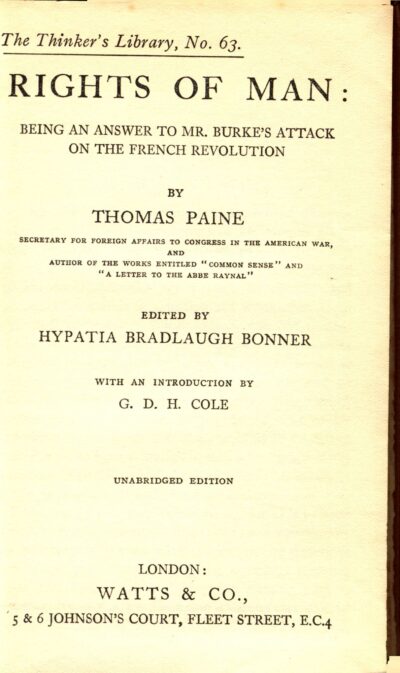

Thomas Paine, Rights of Man (1937)

Thomas Paine was a prominent political theorist and activist who was active in both the American Revolution and the French Revolution.

Born in Thetford England in 1737 as the son of a Quaker, Paine’s life was marked by a series of failures in both career and marriage, until he happened to meet Benjamin Franklin in London who encouraged him to emigrate to America. Arriving in Philadelphia in 1774 as tensions in the American Colonies were rapidly rising in the lead up to the Revolutionary War, he quickly found work editing and writing for the Pennsylvania Magazine.

In January 1776 Paine produced a landmark series of pamphlets dubbed Common Sense which advocated for America to break free from Britain and prepare ‘an asylum for all mankind’. This captured the popular imagination and within a few months sold some 150,000 copies, making it proportionate to population the best-selling work in American history – and a major factor in precipitating the Declaration of Independence.

Paine’s subsequent prominence ensured that he took up a series of jobs for the new United States Government, but from 1787 Paine was back in England observing from a distance the dramatic political events then happening in France. A utopian who believed that society should be remade from the ground-up, he published the Rights of Man as a direct rebuke of Edmund Burke’s condemnatory Reflections on the Revolution in France. Burke had actually defended the American Colonists in their quest for independence because he felt that they were fighting to defend traditional liberties to which they were entitled, but he abhorred the promethean destruction of the French which lacked such cultural roots and went out of its way to try to dismantle all existing institutions.

The book caused such a stir that Paine was charged with treason, but by the time this had happened he had already left England and been elected to France’s new National Convention. However, he was soon to feel the darker side of the political disruption when he was imprisoned by the radical supporters of Robespierre for daring to suggest that they could depose the King without actually killing him.

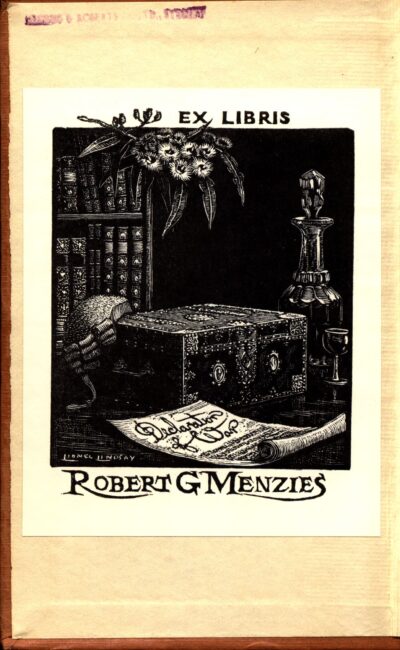

Menzies was a Burkean who always believed that steady and consolidated progress was to be preferred to trying to remake society from the ground up, but he nevertheless had some admiration for Paine’s writings and quoted from him that ‘those who expect to reap the blessings of freedom must undergo the fatigue of supporting it’. But Menzies had far more admiration for Thomas Erskine, the lawyer who defended Paine during his treason trial in absentia for the Rights of Man, and who did so by appealing to time honoured concepts developed through the cumulative evolution of the Common Law, which were the complete opposite of Paine’s ideas of trying to break free of history and precedent.

One of Menzies’s all-time favourite statements, which appears in numerous speeches and broadcasts throughout his career, came from Erskine during Paine’s trial:

‘If I were to ask you, Gentlemen of the Jury, what is the choicest fruit that grows upon the tree of English liberty, you would answer SECURITY UNDER THE LAW. If I were to ask the whole people of England the return they look for at the hands of the Government, for the burdens under which they bend to support it, I should still be answered SECURITY UNDER THE LAW.’

Menzies appreciated that the ‘tree of English liberty’, which Australia had the benefit of inheriting through its political and legal culture and institutions, had taken many centuries to grow in size and strength, and the last thing he would ever want to do was to uproot it.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.