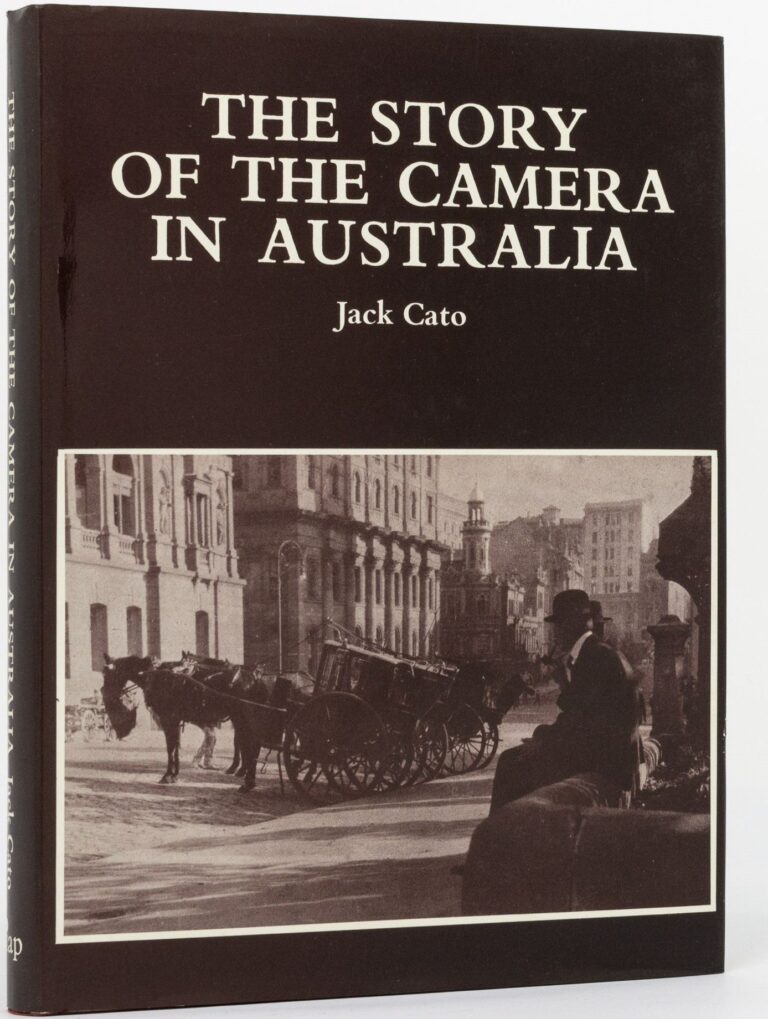

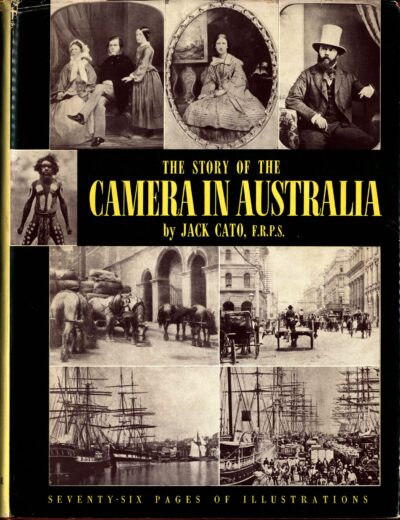

Jack Cato, The Story of the Camera in Australia (1955)

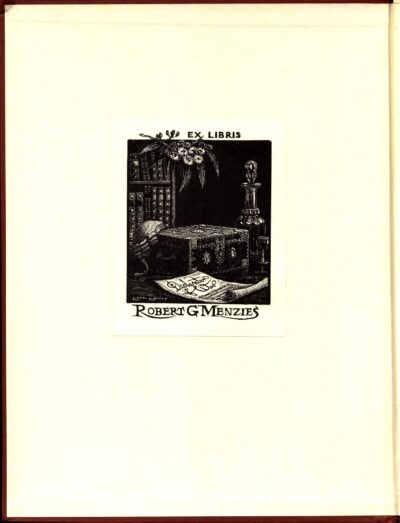

Jack Cato was a famous Australian photographer, and personal friend of Menzies whom he knew via their shared membership of the Savage Club.

Born in Launceston in 1889, Cato’s uncle was a landscape photographer who introduced Jack to the medium at the tender age of six. Jack was soon hooked, such that by 1906 he had set up his own studio in his uncle’s Hobart premises. Cato applied to be the official photographer for Douglas Mawson’s 1911 Australasian Antarctic Expedition, only to be passed up for fellow Book of the Week author Frank Hurley.

Somewhat perturbed, Cato left for England, working for several fashionable photography studios there before moving on to South Africa, where he spent six years producing stunning views and portraits which earned him a fellowship of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain.

Returning home to Australia, Cato was introduced to Melbourne’s socialites by Dame Nelly Melba (who he had met in London), and quickly became the go-to photographer for the city’s leading figures and later photography columnist for the Age.

The Story of the Camera in Australia was a personal passion project which traces the story of Australian photography from the arrival of the first ‘camera obscura’ in the earliest colonial days. With the mid-19th century invention of the daguerreotype people were finally able to permanently capture Australia’s unique landscape, people, and fauna in a far more accurate way than pen and brush allowed. The preface explains enthusiastically that:

‘This is the story of a magic process that was discovered when Australia was young, that was brought out here when it was a year old, and grew and developed side by side with the history of this country, recording every phase of the changing fashions and the life of the generations as no other medium, literary or graphic, could have done.

The bright light, the clear air, and the climate of this country were ideally suited to this process, and the men who worked it here did so with an industry and ingenuity that overcame tremendous difficulties.

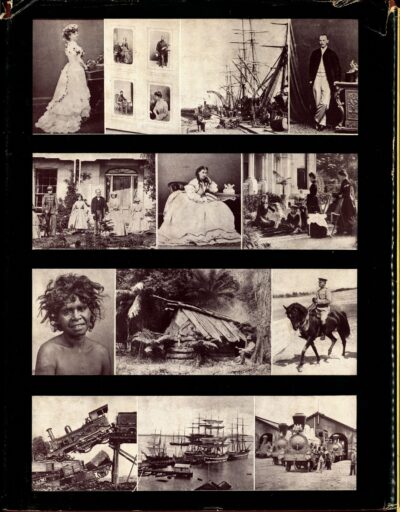

By the nature of their work these men had a front seat to the moving spectacle of a growing nation. They met and knew our famous people, our distinguished visitors, our explorers and pioneers. Often they were the first to explore and view the distant places, recording the beauty and the mysteries of an unknown continent which the bush fire and the vandal have done so much to destroy.

They have left us their records of the rough settlements as they grew into towns; as they extended, year by year, further and further into the bush, and became great cities.

They have shown us how in the crowded capitals and in the lonely settlers’ huts, our people lived and worked and played; how they dressed to stroll the lawns at the Cup, to go to church, and to walk the streets; and, sometimes, how they marched the roads as they went away to war.

They and their cameras have made the days of our years real and vivid to us beyond those of any other age.’

Menzies himself was a camera enthusiast – though primarily of the moving picture, owning one of the first colour home movie cameras in Australia which he used to capture all manner of moments from London in the Blitz to the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. One can easily imagine him enjoying a break from politics, relaxing with Cato in the Savage Club, talking about how best to use his apparatus. In his early years spent in Melbourne’s law district Menzies would frequent the club for lunch, while later as the club’s president (from 1947-62) it was one of his favourite dinner haunts, and a place where he could talk freely and jovially with men who viewed him as a fraternal equal rather than a figure of reverence (or indeed disdain).

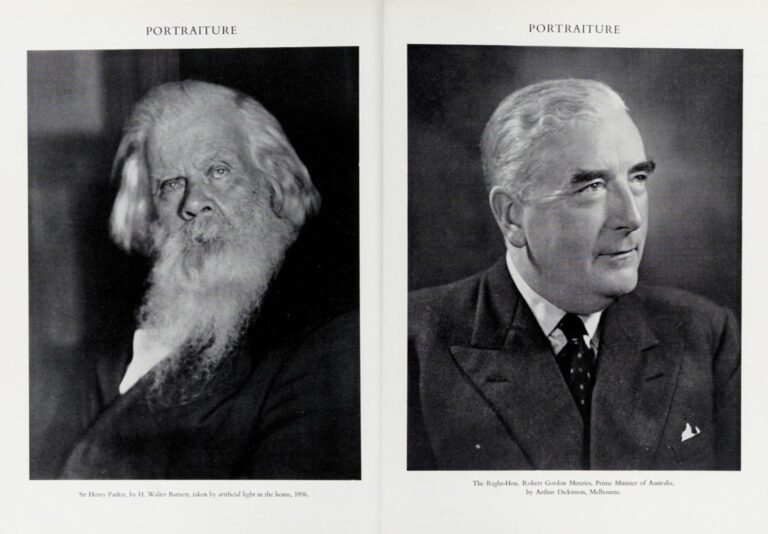

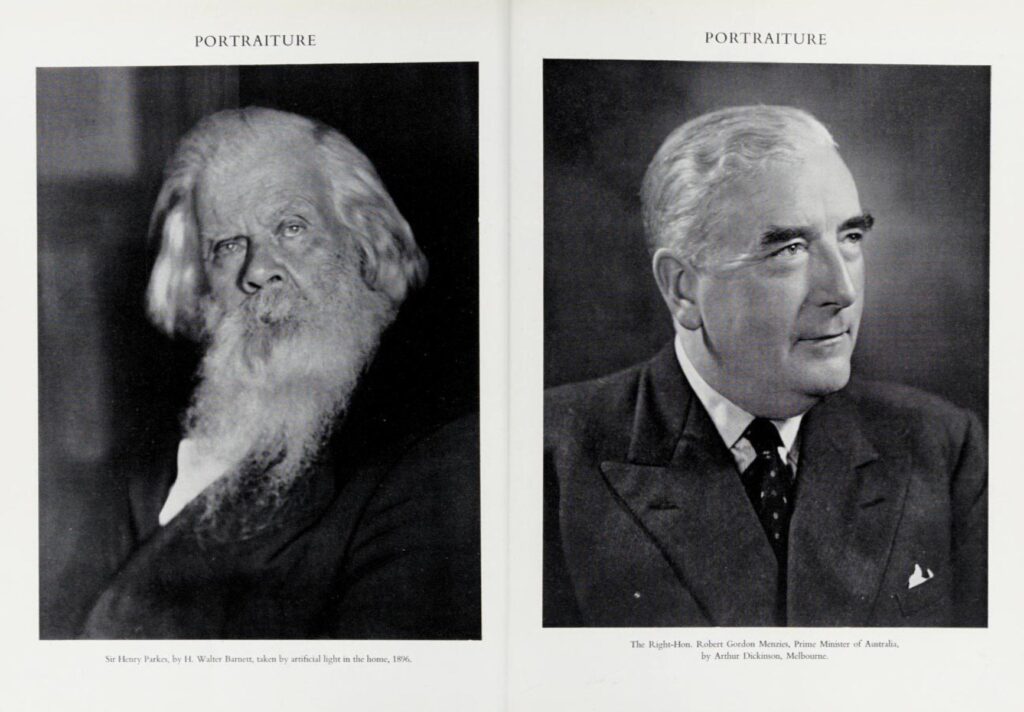

The Menzies Collection contains not only The Story of the Camera in Australia but also a copy of Cato’s autobiography I Can Take It. In the former, Cato made sure to include a photo of then Prime Minister Menzies as a pristine example of Australian portraiture – side by side with a famous photograph of Henry Parkes taken shortly before his death. Cato lauded cameraman Arthur Dickinson for capturing ‘the best’ portrait of Menzies and being ‘a tower of strength to the Salons’.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.