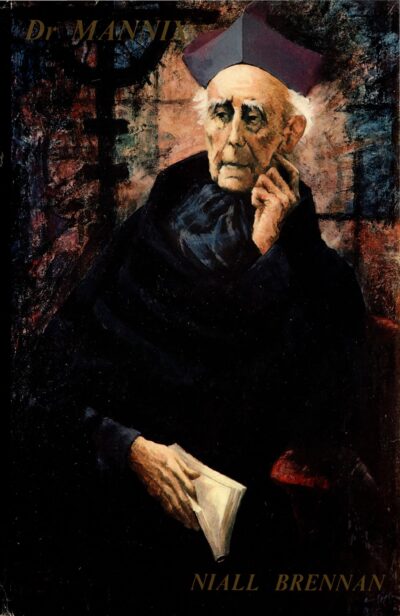

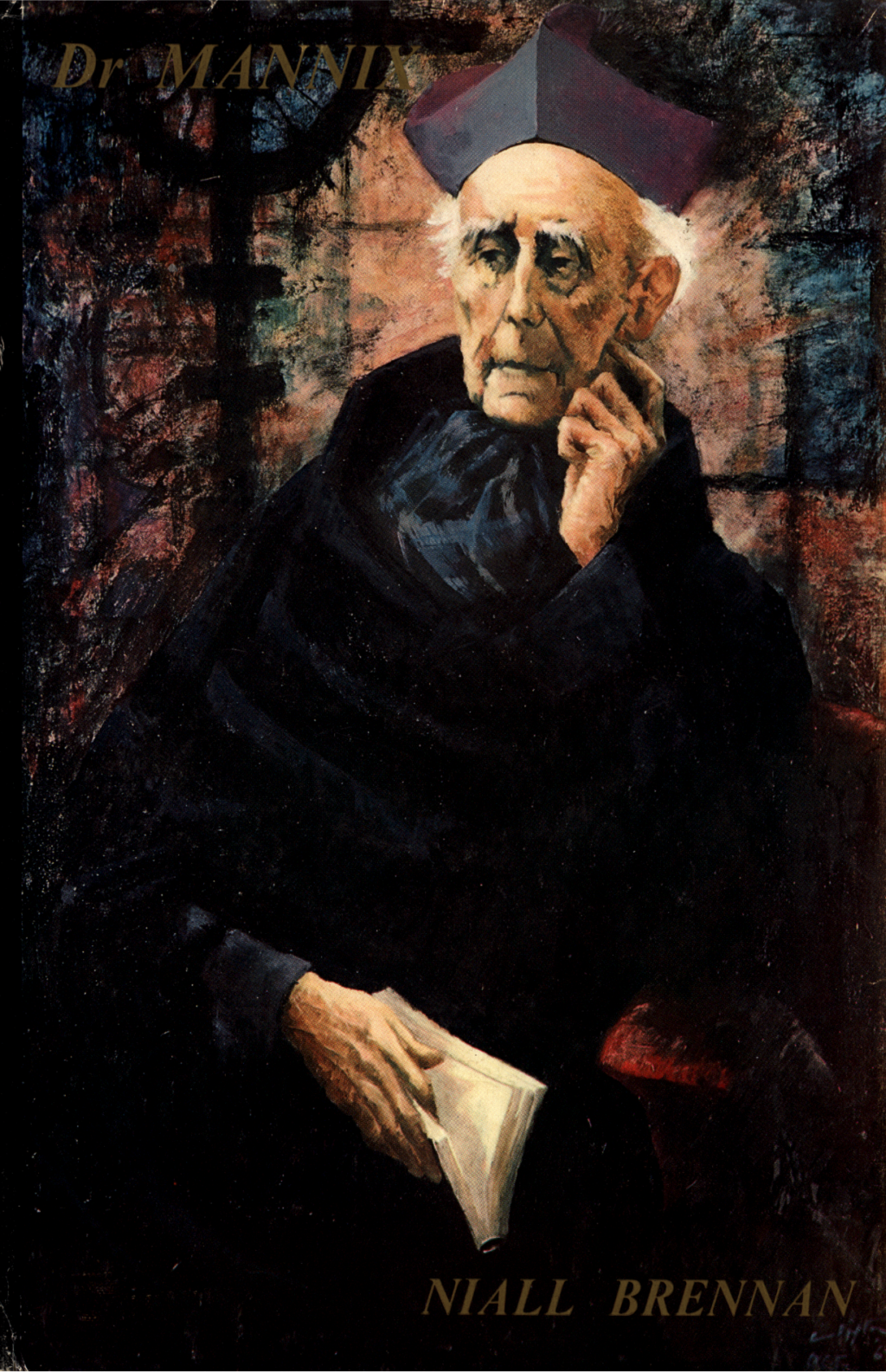

Niall Brennan, Dr Mannix (1964)

Daniel Mannix was the Catholic Archbishop of Melbourne, and a towering figure in within Australia’s Catholic community for many decades.

Born in Cork County Ireland 1864 as the son of a tenant farmer, his parents were both devout and ambitious, and encouraged him to study hard. He attained a Doctorate of Divinity from Dunboyne Establishment, and would lecture in philosophy and serve as chair of moral theology at Maynooth College. Mannix had an interest in politics, and he became the inaugural secretary for the Maynooth Union, a position from which he advocated temperance, co-operatives and housing, and free-enterprise economic nationalism. His position at Maynooth allowed him to climb up the church hierarchy, primarily by ensuring that priests were highly educated, and he was appointed to Melbourne on 1 July 1912 following instructions from Rome.

When he arrived in Australia, he was ‘hailed as a world-class theologian and educationist’ and made it clear from the outset that he would be a vocal advocate for ‘State Aid’ for Catholic schools, believing it unjust that Catholics were forced to pay taxes for schools that refused to cater to their religion. He encouraged Catholics to join the Labor Party and was overtly political, but he only spoke twice to oppose the first conscription referendum in 1916. Nevertheless, Prime Minister Billy Hughes made him a scape-goat for that referendum’s failure, despite the fact that Victoria had recorded a ‘yes’ vote.

The circumstances of the war and the 1916 Easter rising led to a major outbreak of sectarianism in Australia, and Mannix retaliated back against Hughes by speaking out against him in both the 1917 election and the second conscription referendum which followed it. He became a symbol of alleged Irish Catholic ‘disloyalty’ according to Protestant critics, particularly after he refused to remove his hat for the national anthem at the 1918 St Patrick’s Day procession in Melbourne. Herbert Brookes, son in law of Alfred Deakin, led a widespread Protestant campaign calling for Mannix’s deportation, and many others thought that he should be prosecuted for treason. When Mannix went to visit Ireland in the early 1920s, British prime Minister Lloyd George would try to bar his entry, going so far as to dispatch a warship to prevent Mannix’s landing.

During the 1930s Mannix was a major driving force behind the Catholic Action movement which would ultimately feed into the Labor Split of the 1950s. But he was initially on good terms with Evatt, whom he consulted on the need for constitutional safeguards for religion ahead of the 1944 powers referendum. Despite being a strong anti-Communist, he opposed the 1951 referendum to ban the party. After the split however, Mannix became a powerful backer of the Democratic Labour Party, and therefore in a roundabout way an ally of Menzies.

That being said, the two men had always maintained something of a cordial relationship, as Menzies tried to rise above the sectarian strife that gripped Melbourne in the aftermath of the Great War. As a Victorian state MLC in 1928, Menzies attended the opening of a local Catholic School in his East Yarra Province where he shared a platform with Mannix, for which he was bitterly scolded by his parents. In the lead up to the 1954 Royal Tour, there was a controversy surrounding the fact that the trooping of colours at Duntroon would involve Catholic soldiers in an Anglican religious ceremony, and Mannix ultimately gave Catholics special dispensation to do so.

But perhaps the most important aspect of the relationship between the two men is that it was Robert Menzies who finally broke through the sectarian barrier to allow State Aid for Catholic and non-government schools, an issue which had been the focal point of Mannix’s career in Australia. Mannix only found out three days before his death in November 1963, and he credited the DLP with forcing what was a heartening breakthrough.

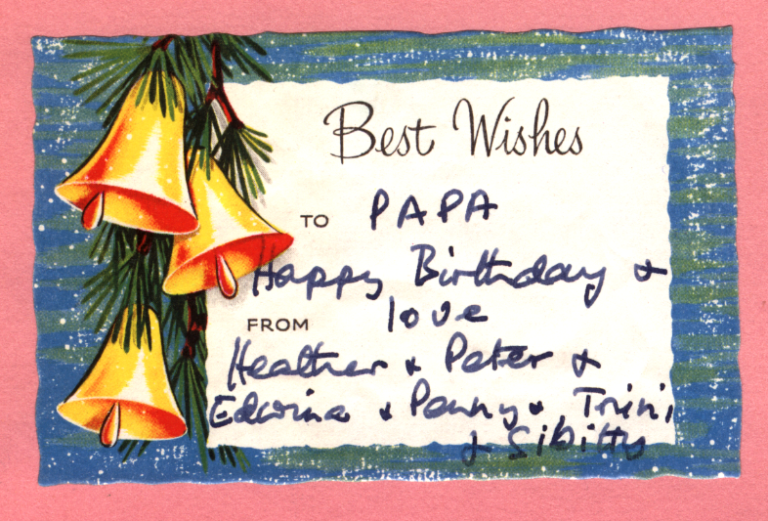

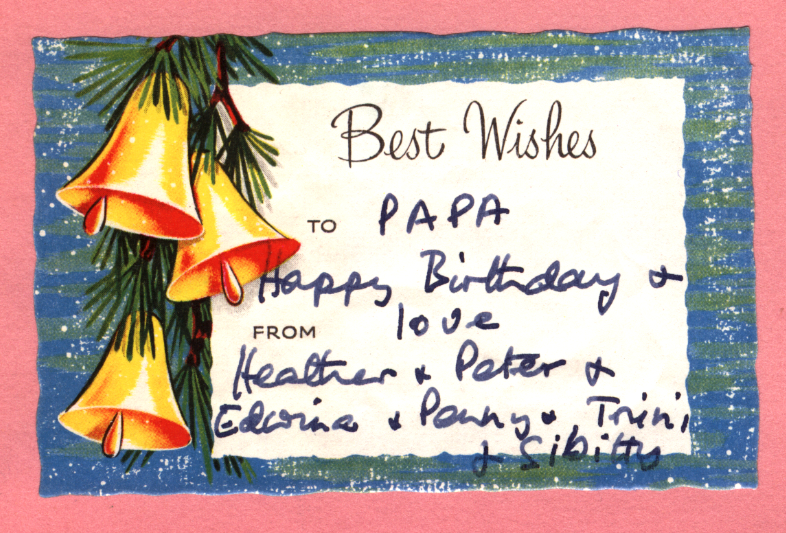

Menzies’s copy of Dr Mannix, authored by prominent pacifist Neill Brennan, was a birthday gift given to him by daughter Heather in December 1964, the year he had legislated State Aid. It says a lot about Menzies’s open attitude towards Catholics, that his intimate family thought he would like to know more about a divisive figure who had generally been reviled on Menzies’s side of politics.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.