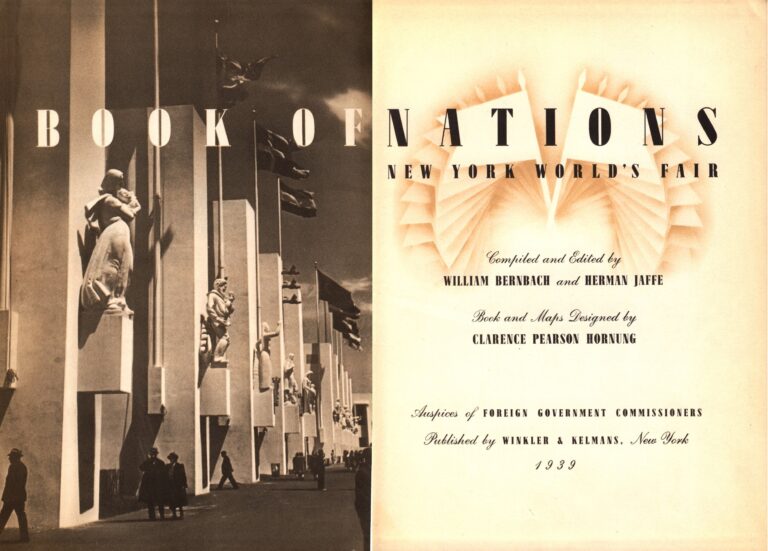

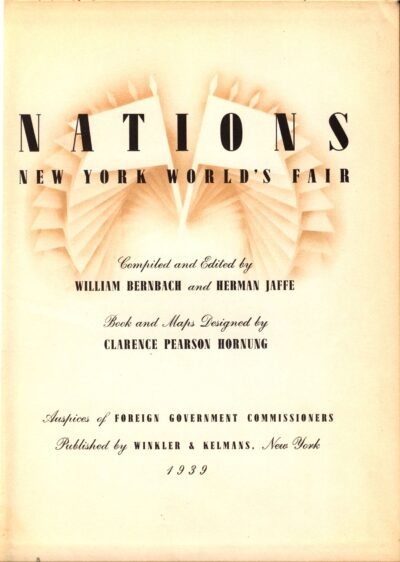

William Berbach & Herman Jaffe, Book of Nations: New York World’s Fair (1939)

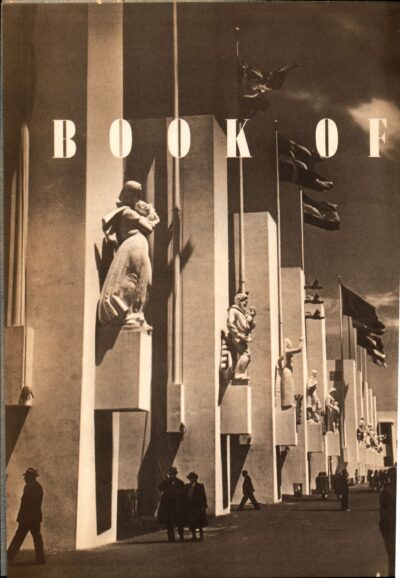

‘World’s Fairs’ are a series of international exhibitions designed to show off national achievements, promote trade, and foster cultural exchange. While they have a history that can be dated back to the 18th century, they arguably reached their peak between the late nineteenth century and the Second World War, a time in which nationalism provided a spur for displays of national pride, rapid technological change provided a wealth of new technologies to show off and promote, and this in turn attracted enormous crowds who were willing to put up with huge lines to witness the wonders of the latest advancement.

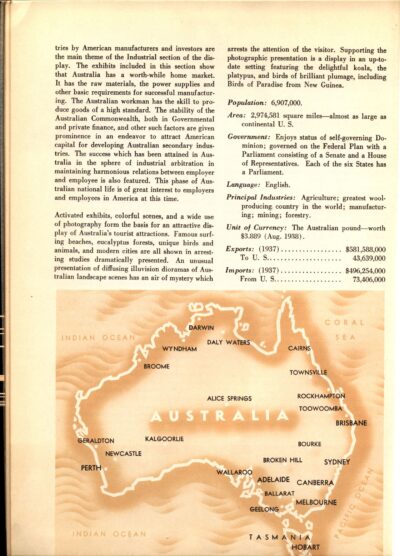

As a young nation which relied on agricultural exports to support its economy, Australia was naturally attracted to these opportunities for self-promotion, particularly in their more limited form of Empire exhibitions which had developed out Prince Albert’s famous ‘Great Exhibition’ of 1851. Before WW2 the vast majority of Australian trade was conducted within the British Commonwealth of Nations, enjoying the benefits of a favourable system of ‘imperial preference’ which involved having lower tariffs for internal empire trade while increasing customs barriers for the rest of the world, hence this targeted audience was generally the most lucrative. Nevertheless, Australia hosted its own Melbourne International Exhibition in 1880, the first internationally recognised world’s fair in the southern hemisphere, and the event for which the still standing Royal Exhibition Building was built.

The 1939 World’s Fair was a watershed moment in the history of the cultural phenomena, as it drew to a close the 1851-1938 heyday of celebrating and advancing industrialisation. In 1939, with the drums of war steadily building in the background, the focus shifted towards cultural themes and social progress. The aim was to promote international harmony, precisely at the moment when any such harmony was rapidly deteriorating.

Australia put together an innovative pavilion, designed by Sydney architects, Stephenson & Turner, who worked with graphic designer Douglas Annand ‘to create a flowing, multi-level space that integrated sculpture, photography, murals and displays about flora, fauna and industry’. A novel invention called the ‘Illuvision’ featured full colour, three dimensional, mechanised dioramas which attempted to capture the majesty of the Australian landscape for those who had never witnessed it. There were eight such dioramas, including one depicting a Sydney waterside, showing off the Harbour Bridge to a New York audience appreciative of feats of engineering; while the ‘Illuvision’ screen itself was framed by Aboriginal motifs of hunting and fishing designed to emulate rock art.

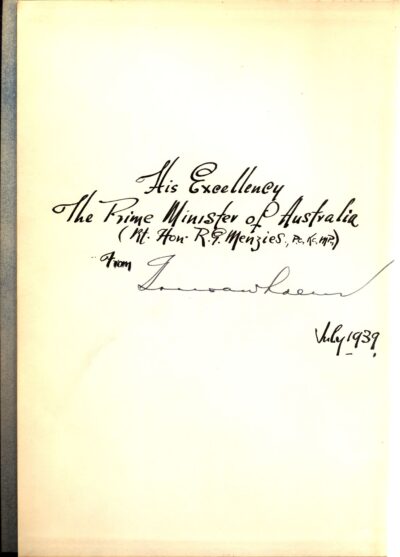

For the fair’s ‘Australia Day’ on 11 August the display even featured the voice of then Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies, who was broadcast on station WJV New York:

‘Good evening, America. Good evening, from the Commonwealth of Australia, from your friends and neighbours across the Pacific. Today is Australia Day at the New York World’s Fair. No doubt many of you have been to the fair and amongst the great national exhibits you have managed to find the Australian pavilion. Our exhibit is far more than a commercial exhibit. It is in fact intended as a graphic message of goodwill from one English speaking country to another. Whenever we meet there is an instinctive bond between us. We are both strongly democratic. We both hate formalities and distrust pomposity. We both put a high premium on the character and powers of the individual. We both have a fresh and optimistic attitude, an outlook on life and its possibilities. In short, we speak to each other in language and with ideas that the other fellow can at once understand. If I may say so, we are bound to be friends. This does not mean that there is any loosening of our ties with our mother country, Great Britain. We the British people of Australia can never fail to appreciate that there is a special link between ourselves and America.’

While the fair could do little to forestall the outbreak of hostilities, it still marked a key moment in Australia’s growing presence on the world stage, and particularly our reputation in America, which would greatly increase during WW2 when US General Douglas MacArthur stationed his headquarters here. Menzies’s copy of Nations: New York World’s Fair is therefore a notable souvenir of a final moment of optimism and hope before the declaration of war.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.