M.H. Ellis, The Garden Path: The Story of the Saturation of the Australian Labour Movement by Communism (1949)

Malcolm Henry Ellis was a conservative journalist and historian, who had a significant impact on Australian political life during the twentieth century.

Born on a remote Queensland cattle station in 1890, Ellis had a hard childhood growing up in the depression of the 1890s but nevertheless came to idolise rural life. He was lucky enough to win a bursary to attend Brisbane Grammar School, where he excelled academically and came to edit the school magazine, giving him an early taste for journalism. At the time, there was no university in Queensland, so despite his academic gifts, Ellis went straight into his trade, picking up a cadetship with the Brisbane Daily Mail.

During the First World War, Ellis tried to enlist, but he was rejected for active service because a childhood accident had blinded him in one eye. In 1918 he was appointed to the executive of a war propaganda committee, and he became a fierce critic of the Labor Party whom he believed were guilty of disloyalty, developing a close relationship with W.M. Hughes and publishing A Handbook for Nationalists.

In December 1920 Ellis joined the Daily Telegraph in Sydney as chief political correspondent, giving him access to a greater audience and consequent political influence. Boasting the ability to write a three thousand word article on any subject within 24 hours, Ellis spent much of the 1920s as a travelling reporter in Papua, New Guinea, London and India. With the onset of the Great Depression, Ellis became an early critic of Australian communism, publishing The Red Road (The Story of the Capture of the Lang Party by Communists, Instructed from Moscow). In 1933 he joined The Bulletin, and he would essentially shape the magazine in his own image for the next thirty years.

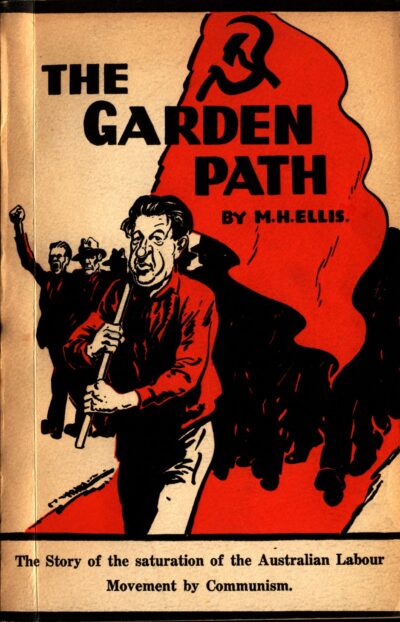

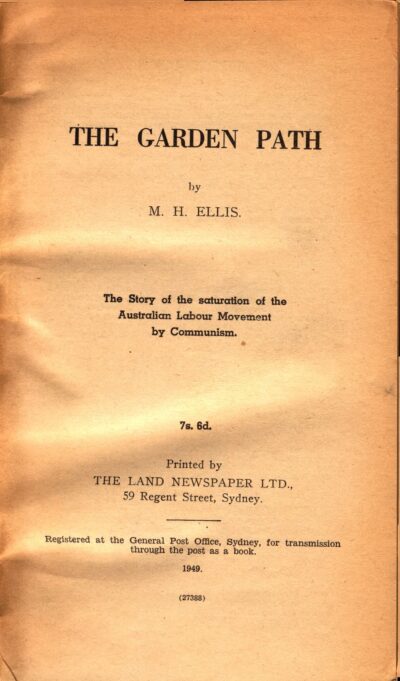

Ellis became somewhat close with Menzies, and would play an important role in the political developments of the late 1940s, both as a mastermind of the campaign against bank nationalisation, and continuing his role as a ‘whistleblower’ on the extent of communist infiltration in Australia. His 1949 book The Garden Path (a pun title alluding to Australian communist Jock Garden), built on his earlier work and tried to establish a direct link between the ALP and the communists in terms of their political objectives:

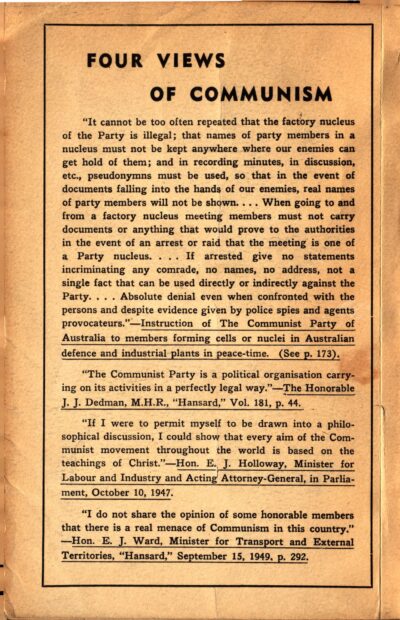

‘The present Labour objective – Socialisation, with its adjunct of a Soviet-form Supreme Economic Council – was imported straight from Russia and forced on the Labour Party by the galaxy of Communists and Communist sympathisers who formed a drafting committee of the 1921 T.U.C. Conference. Its adoption brought congratulations to the local Communists direct from Moscow. “Socialisation” means socialisation as the Communists mean it, whatever differences there are between the two parties as to how it may be achieved or how administered.’

Such was the power of the book’s message, that thie Liberal Party itself came to sell copies. Though Ellis was clearly a sensationalist, he was a meticulous evidence gatherer, and even a Labor historian has admitted that ‘Ellis’s polemical writings were usually quite sound in terms of empirical detail’. He collected so much primary material on the Communist Party of Australia that he would eventually donate it to the National Library for the benefit of future historians, and he served on the 1949 Victorian royal commission into communism as the ‘historical expert’ of Australian communism, and this received a great deal of publicity which helped to set the scene for the federal election of the same year.

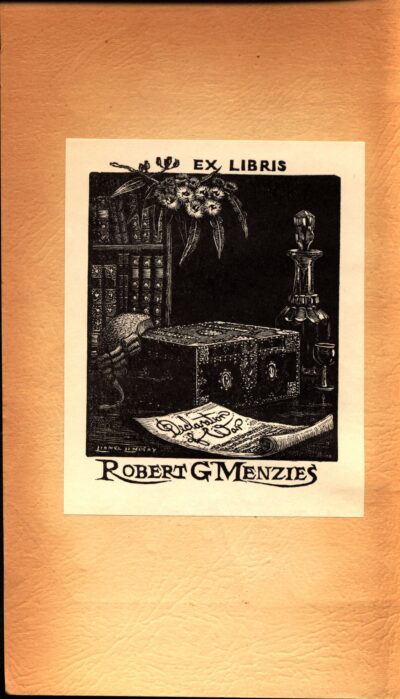

The Menzies Collection contains a large number of Ellis’s works, not just The Red Road and The Garden Path, but also more traditional histories like biographies of John Macarthur and Lachlan Macquarie, suggesting that Menzies paid close attention to Ellis’s output. As Cold War warriors, the two men had complementary worldviews and intertwined careers, but none of the books’ inscriptions suggest a truly close relationship, the most sentimental being:

‘With the sympathy of a member of a craft whose works are generally received with more genial tolerance than those of Prime Ministers; also, with an abundance of good wishes’ 1955.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.