J.T. Lang, The Great Bust: The Depression of the Thirties (1962)

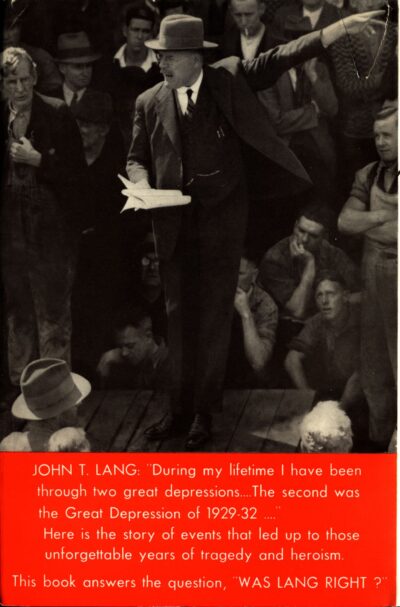

Jack Lang is one of the most controversial figures in Australian political history. The Labor Premier of New South Wales during much of the Great Depression, his call to repudiate Australia’s debts horrified middle class conservatives and threatened the financial stability of the nation. On his own side of politics, Lang was responsible for severely splitting the Labor Party, and ironically presaged the formation of the DLP through his creation of the Australian Labor (Non-Communist) Party in the 1940s. Menzies for his part described Lang as a ‘financial and political burglar’, but he said on several occasions that he respected that Lang was at least honest and upfront about his radical views, and that there was no hypocrisy about him.

In 1932 the climax of the Lang saga and a long-running dispute with Prime Minister Joseph Lyons saw Lang dismissed as Premier by NSW Governor Philip Game for instructing public servants to deliberately disobey federal law, thereby setting something of a precedent for Gough Whitlam’s later dismissal. Lang took his dismissal quite well – avoiding the sort of destabilising call for revolution that many had feared, and he would spend much of his time in retirement writing self-justifications for his political actions.

One of these self-justifications was The Great Bust – Lang’s personal account of the Great Depression. The publisher sent Menzies a copy, as he is mentioned several times throughout the book. As you would imagine, Lang is generally highly critical of Menzies, suggesting that he was ‘superficial’ whereas Country Party Leader Earle Page (with whom Menzies often clashed) was more ‘constructive’, and also accusing Menzies as a lawyer of disproportionately taking legal briefs from the big end of town. Nevertheless, the book contains a notable account Menzies and H.V. Evatt facing off in an important but now largely forgotten court case heard in 1930.

The dispute was over whether the Arbitration Court would throw out an award for railway workers which had been created before the onset of the Depression and which was now entirely out of step with market rates. This revealed one of the flaws of Australia’s heavily regulated arbitration system, which was that it was inflexible and slow to react to changes in the economy. Had the award been insisted upon (Menzies argued), not only would it have been unaffordable for State governments which were already on the brink of bankruptcy, but many more railway workers would have had to be laid off in order to keep the remaining ones on their high wages and benefits. Menzies won the day, much to Lang’s chagrin:

‘Menzies had won the first round. He had achieved the distinction of being the first advocate to get rid of an award for the employers without a strike in the industry. There was no dispute. It was a death blow to the arbitration system. All margins for skill in the Railways were lost. There was no longer guarantee of full-time employment. Superannuation was in jeopardy. Rationing of work was simply a matter of issuing the edict.’

Menzies thus helped to set an important precedent that would greatly assist Australian Governments to remain solvent, ensure the pain and sacrifices of the Depression were shared by those in secure government employment, and arguably saved a number of jobs.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.