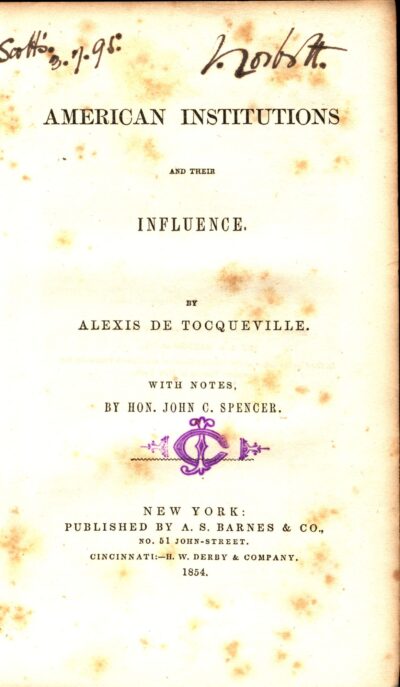

Alexis de Tocqueville, American Institutions and their Influence (1854)

Alexis de Tocqueville was a French political scientist, historian, and politician, who made a major contribution to liberal thought through his seminal Democracy in America, written after visiting a young United States during the 1830s. A member of the centre-left in French politics who thought that America’s broad democracy was a model of where European politics was heading, he nevertheless came to warn about how absolutist majority rule and the imposition of equality could pose a threat to individual freedom.

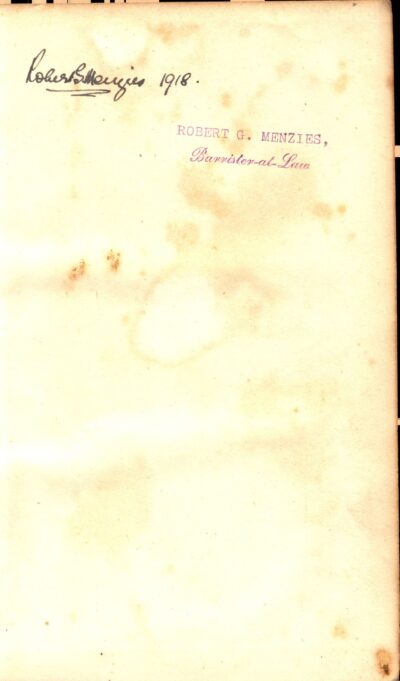

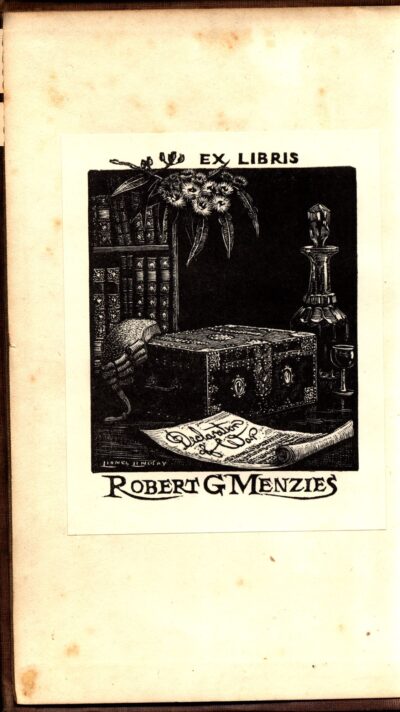

American Institutions and their Influence, which Menzies bought a copy of in 1918 around the time he began his career as a lawyer – a copy which is marked by signs of intensive use, forms the second half of Democracy in America, but it arguably contains its most notable passages including Tocqueville’s discussion of the ‘tyranny of the majority’ which could be just as devastating as the tyranny of any dictator:

‘The very essence of democratic government consists in the absolute sovereignty of the majority: for there is nothing in democratic states which is capable of resisting it…. A majority taken collectively may be regarded as a being whose opinions, and most frequently whose interests, are opposed to those of another being, which is styled a minority. If it be admitted that a man, possessing absolute power, may misuse that power by wronging his adversaries, why should a majority not be liable to the same reproach? Men are not apt to change their characters by agglomeration; nor does their patience in the presence of obstacles increase with the consciousness of their strength. And for these reasons I can never willingly invest any number of my fellow-creatures with that unlimited authority which I should refuse to any one of them…

Unlimited power is in itself a bad and dangerous thing; human beings are not competent to exercise it with discretion; and God alone can be omnipotent, because his wisdom and his justice are always equal to his power. But no power upon earth is so worthy of honour for itself, or of reverential obedience to the rights which it represents, that I would consent to admit its uncontrolled and all-predominate authority. When I see that the right and the means of absolute command are conferred on a people or upon a king, upon an aristocracy or a democracy, a monarchy or a republic, I recognise the germ of tyranny, and I journey onward to a land of more hopeful institutions.

In my opinion the main evil of the present democratic institutions of the United States does not arise, as is often asserted in Europe, from their weakness, but from their over-powering strength; and I am not so much alarmed at the excessive liberty which reigns in that country, as at the very inadequate securities which exist against tyranny.

When an individual or a party is wronged in the United States, to whom can he apply for redress? If to public opinion, public opinion constitutes the majority; if to the legislature, it represents the majority, and implicitly obeys its instructions: if to the executive power, it is appointed by the majority and is a passive tool in its hands; the public troops consist of the majority under arms; the jury is the majority invested with the right of hearing judicial cases; and in certain states even the judges are elected by the majority. However iniquitous or absurd the evil of which you complain may be, you must submit to it as well as you can.

If; on the other hand, a legislative power could be so constituted as to represent the majority without necessarily being the slave of its passions; an executive, so as to retain a certain degree of uncontrolled authority; and a judiciary, so as to remain independent of the two other powers; a government would be formed which would still be democratic, without incurring any risk of tyrannical abuse.’

This was a theme that Menzies would pick up on very strongly in his Forgotten People broadcasts, in which he said directly that ‘the despotism of a majority may be just as bad as the despotism of one man’. He went on to say that ‘it is true, as wise men have said for a hundred years, that the real test of liberty in any country is the way in which minorities are treated’, and suggested that Mussolini ‘realised that the great enemy of autocratic authority is the lively minority, and he therefore determined that minorities should not count and that the law of the majority should be a tyrant’s law’.

Menzies talked about the need for both the voting public and politicians to exercise moral independence and not be swayed by the emotions of the crowd. Indeed, he suggested that ‘the moment a man seeks moral and intellectual refuge in the emotions of a crowd, he ceases to be a human being and becomes a cipher.’ This is part of the reason why Menzies wanted a stake-holder democracy where people owned their own homes, this security would give them the ability to think about the national interest and not merely use their vote to enhance their own financial position or to curry favour with their neighbours. Menzies also warned against pressure politics, and people trying to intimidate politicians to vote how they wanted. He had a Burkean view of the role of a Parliamentarian who was not to merely be a delegate obeying the wishes of their electorate, but a free-thinking individual tasked with bringing their mature judgement to each important issue, which in effect meant representing the majority without ‘being the slave of its passions’.

Menzies saw individual brilliance as the main force behind human progress, and warned that the majority could stifle such brilliance in a manner that reflected Tocqueville’s warnings about democracy’s imposed uniformity. In a broadcast delivered in August 1942, Menzies recalled that ‘a few weeks ago I listened to a Scots Presbyterian Preacher who had some good things to say to the effect that the world’s progress had never depended upon the ideas produced by the majority but had always depended upon the burning faith of a relatively few men. That is something worth thinking about. It is perhaps not untrue to say that if in the history of the last hundred years everybody had been compelled to subscribe to what the majority thought, there would have been no progress in the world and we should have become merely a community of dumb and driven cattle’.

Menzies was overall confident in the basic premise of democracy, that the majority would ultimately make wise decisions or at least wiser decisions over the long term. But he believed that in the short term the majority was very often wrong, and that is why free speech was so important, so society could engage in the kind of rigorous debate where the majority could ultimately be persuaded of their error. Menzies famously believed that the basis of democracy was ‘the Christian conception that there is in every human soul a spark of the Divine’, but for that exact reason he did not want the majority trampling on any individual, and insisted that ‘the law’s greatest benefits are for the minority man – the individual.’

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.