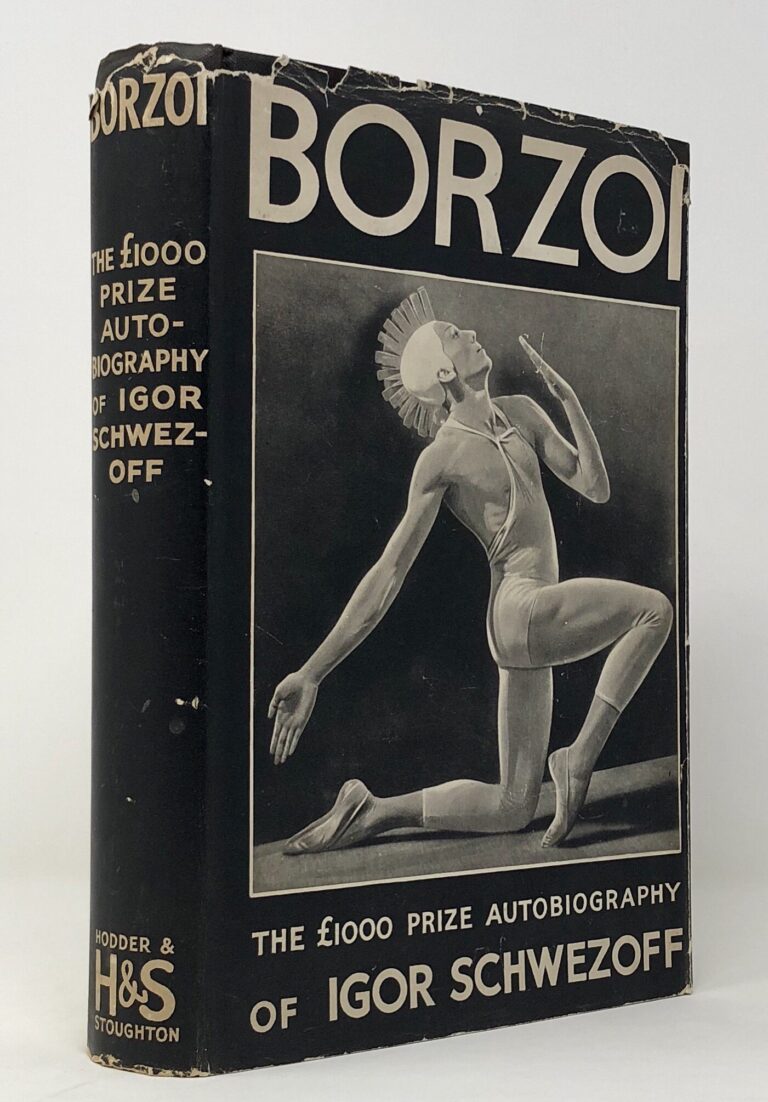

Igor Schwezoff, Borzoi (1938)

Igor Schwezoff was a famous Russian ballet dancer who experienced the horrors of the Russian Revolution, defected to the West, and went on to have a stellar career.

Born in St. Petersburg in 1904 to a well-connected military family, Schwezoff received an extensive education that included being tutored in six languages. The drawback of such luxurious beginnings was that his prosperous family were natural targets of the Bolsheviks’ anti-bourgeois campaign. Just 13 years old when they came to power, his father suffered terribly before fleeing the country and his abandoned mother soon died of ‘misery and starvation’ as the family was stripped of all its worldly possessions. Amidst this despair, Schwezoff found redemption in dance, recalling that:

‘although they mistrusted me because I was a bourgeois, although I had no clothes, little food, no money, I could live for my dancing. And I thought, stupidly, that if I could but get out of Russia and come to Europe I could teach people to love the ballet’.

Schwezoff and his younger sister lived for a time in a bathroom of a small Leningrad flat, the only place they could find to shelter them from the harsh Russian winter. However, his talent was undeniable, such that he soon found work performing propagandist dances which sought to glorify the regime. Believing that ‘a communist artist is actually a contradiction of terms’ because art was ultimately about freedom of individual expression, he toured the USSR as part of a state-sanctioned ballet company and bided his time waiting for a chance to escape.

In 1930 a trip to Vladivostok on the eastern edge of the Soviet Union provided an opportunity, and Schwezoff seized it, walking on foot for three days in only ballet shoes to cross the Chinese border to the city of Harbin in Manchuria, which had a large ethnically Russian population and was a town through which many fled the Soviet Union. Schwezoff recalled waiting anxiously, nursing his swollen and wounded feet, as the Chinese officials scrutinised his papers and finally granted him asylum.

Several months later Schwezoff arrived in Paris, and quickly found work with the Original Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. He then went to Argentina, dancing in the National Theatre of Buenos Aires under the direction of famed Russian choreographer Michael Fokine, before returning to Europe. By the mid 1930s he was touring internationally with the Ballet Russe, and in late 1939 he arrived in Australia for a wartime series of performances that garnered rave reviews from critics.

This was at a time during which the Soviets had been fighting essentially alongside the Nazis, and on arriving in the country Schwezoff told pressmen how the success of the Finns against the ongoing Russian invasion of their homeland showcased the determination and skill of the ‘white Russians’ like his family. Highly sympathetic towards Poland which was being ravished simultaneously by the forces of Nazism and Communism, during his visit Schwezoff held midnight concerts raising money for the Polish Relief Fund.

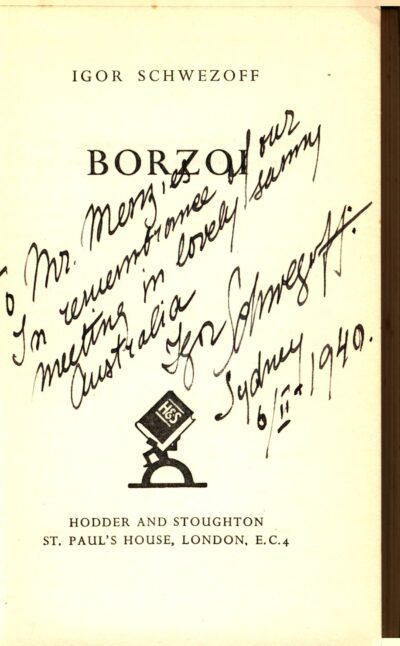

It was during this time that Schwezoff met and enjoyed an evening with Prime Minister Robert Menzies, giving him a copy of Borzoi signed ‘To Mr Menzies, In remembrance of our meeting in lovely sunny Australia, Igor Schwezoff, Sydney, 6/II/1940’. The book was an award winning and best-selling autobiography documenting Borzoi’s life and struggle for freedom. Its title came from a rather deprecating nickname of Schwezoff’s, whose friends believed that he resembled the dog-breed, partly on account of his lanky dancer’s frame.

Such personal accounts of fleeing Soviet totalitarianism would become very prominent during the Cold War, but as an early example the book may have been influential in shaping Menzies’s attitudes towards the USSR. Indeed, given the book’s popularity, the number of Australian newspaper reviews of it documented in Trove, and the fame Schwezoff garnered from his Australian performances, the book may more firmly be said to have helped inform the broader Australian public’s opinion on Russia in the period before it became an ally (and thus was temporarily showered with praise).

By the time of his death in the early 1980s, Schwezoff had spent decades working as one of the world’s leading ballet teachers in New York, Washington and Tokyo. He continued to harbour dreams of visiting his homeland, but dared not go back while the communists remained in power. An artist until the end, he said that:

‘I do not believe in art that does not convey to one some feeling. Art is not something nice, sweet or pretty. It is more than that. Art is something vital. It may be beautiful or even hideous, but it must be deep and strong in its expression. Art is not, and should not be mechanical. It must always be alive.’

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.