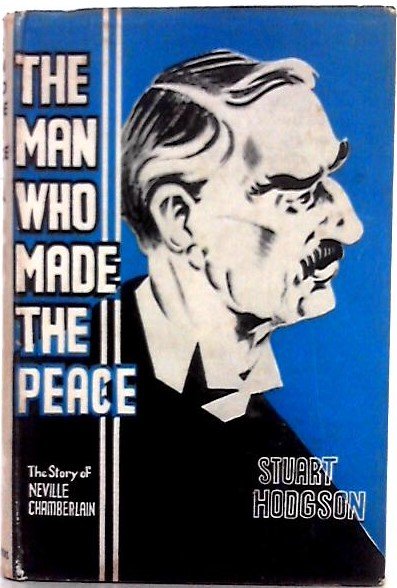

Stuart Hodgson, The Man Who Made The Peace: The Story of Neville Chamberlain (1938)

John Stuart Hodgson (1877-1950) was a journalist and author best known for working as the editor of the left-leaning Daily News newspaper. He authored three books The Liberal Policy for Industry (1928), Portraits and Reflections (1929), and The Man Who Made The Peace: The Story of Neville Chamberlain (1938). The latter was a quickly-produced biography, outlining the life of Britain’s then Prime Minister from his early days in Birmingham (where he served twice as mayor), his entrance to the House of Commons in 1919, and subsequent rise up the ministerial ranks of the British Liberal Party.

Despite owning a copy, Robert Menzies always had always expressed great contempt for such rushed and ill-researched contemporary political histories. In his introduction to his memoir Afternoon Light he explained that:

‘I have no great faith in it [contemporary history]. What is the source material? All too frequently, in my experience, it consists of newspaper material (almost all of which is slanted one way or another), and does not stop short of the gossip column.’

This was certainly true of The Man Who Made The Peace, which amounted to little more than a hagiography trying to cash in on Chamberlain’s then sky-high popularity after he had allegedly secured ‘Peace for our time’ at the Munich Conference in which Hitler was gifted much of Czechoslovakia. The book would be of little note, were it not for its tragically ironic title and the way in which it serves as an artefact attesting to the widespread support for what is known as ‘appeasement’.

Menzies is often accused of being an ‘appeaser’ but his views were quite unremarkable at the time and indeed the United Australia Party repeatedly tried to increase Australia’s defence spending during the 1930s in preparation for a potential conflict, only to be rebuffed by the Labor Party whose leader John Curtin referred quite conspiratorially to ‘a class that has a vested interest in war and war-making’. Notably Hodgson lauded Chamberlain’s apparent ‘victory’ for peace in similar class-based terms:

‘The fact is, that for the first time in history the voice of the common people of all countries, as the horrible shadow of war darkened their homes, made itself heard, and decisively. A man was found to give it expression, and it prevailed — prevailed even at that eleventh hour, when the issue had almost passed out of the hands of politicians and the military machines in all countries had started on their daily course. And what has been done once may, and will be, done again. The people know their power now. The politicians know that it is possible to mobilise opinion for peace as well as for war; and that he who does so effectively is assured of a triumph such as no military conqueror can win, be his victories never so great. There may be other wars and rumours of war. The shadows may darken again the homes of countless thousands of perfectly innocent people. But next time there will be the same reaction; and next time it will be easier to organise it. That knowledge is the great prize which has been won; and the man to whom the world owes it, and knows that it owes it, is Neville Chamberlain.’

Menzies naturally came to regret appeasement, but he was quite upfront about how universal its support had once been and how many people tended to treat their previous stance with deliberate amnesia. During his Forgotten People series of radio broadcasts he lamented that during the mid 1930s a high military budget ‘would have been regarded as a piece of war-mongering hysteria’.

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.