Sir Thomas Smith, De Republica Anglorum: A Discourse on the Commonwealth of England (1906)

Sir Thomas Smith was an English scholar, parliamentarian and diplomat who served in the court of Queen Elizabeth I. He is now best remembered as an important political theorist, who captured the essence of the unwritten British Constitution at an important time in its development.

Born in Essex in 1513, Smith came from an aristocratic background and attended Queens’ College, Cambridge, before studying in France and Italy and taking a degree in law at the University of Padua. An early convert to Protestantism, Smith rose to prominence during the reign of Edward VI, becoming Secretary of State and taking charge of an important diplomatic mission to Brussels. When the Catholic Mary became Queen he lost all his offices, but he survived her reign and returned to power with the ascent of Queen Elizabeth, who appointed Smith Ambassador to France.

It was while living in France that Smith wrote De Republica Anglorum, a piece of political theory which sought to describe the British Commonwealth in favourable terms that contrasted with France’s alleged despotism. The book described England as having a mixed constitution, in which the monarch, nobility and the people all shared power via the institution of Parliament. The book is most notable for its enduring definition of the supreme role of Parliament, which shows that certain customs like reading a Bill three times had already established themselves in the 16th century:

‘The most high and absolute power of the realm of England, consists in the Parliament. For as in war where the King himself in person, the nobility, the rest of the gentility, and the yeomanry are, is the force and power of England: so in peace and consultation where the Prince is to give life, and the last and highest commandment, the Barony for the nobility and higher, the knights, esquires, gentlemen and commons for the lower part of the commonwealth, the bishops for the clergy be present to advertise, consult and show what is good and necessary for the commonwealth, and to consult together, and upon mature deliberation every bill or law being thrice read and disputed upon in either house, the other two parts first each apart, and after the Prince himself in presence of both the parties doeth consent unto and allow. That is the Prince’s and whole realm’s deed: whereupon justly no man can complain, but must accommodate himself to find it good and obey it.

That which is done by this consent is called firm, stable, and sanctum, and is taken for law. The Parliament abrogates old laws, makes new ones, giveth orders for things past, and for things hereafter to be followed, changes rights, and possessions of private men, legitimates bastards, establishes forms of religion, alters weights and measures, giveth forms of succession to the crown, defines of doubtful rights, whereof is no law already made, appoints subsidies, tails, taxes, and impositions, giveth most free pardons and absolutions, restoreth in blood and name as the highest court, condemns or absolves them whom the Prince will put to that trial: And to be short, all that ever the people of Rome might do either in Centuriatis comitis or tributis, the same may be done by the Parliament of England, which represents and hath the power of the whole realm both the head and the body. For every Englishman is intended to be there present, either in person or by procuration and attorneys, of what preeminence, state, dignity, or quality soever he be, from the Prince (be he King or Queen) to the lowest person of England. And the consent of the Parliament is taken to be every man’s consent.’

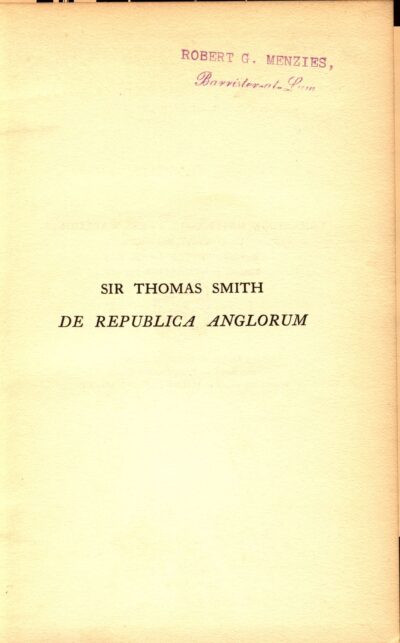

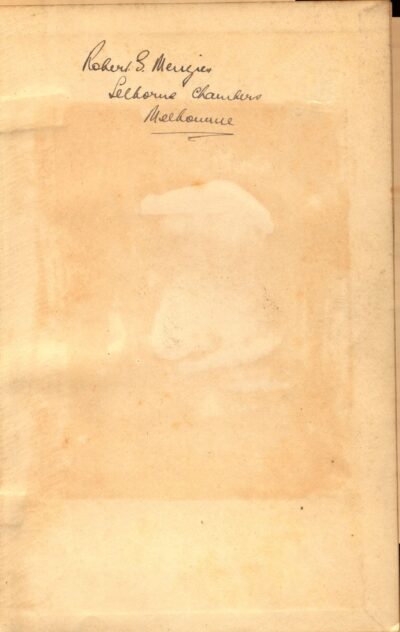

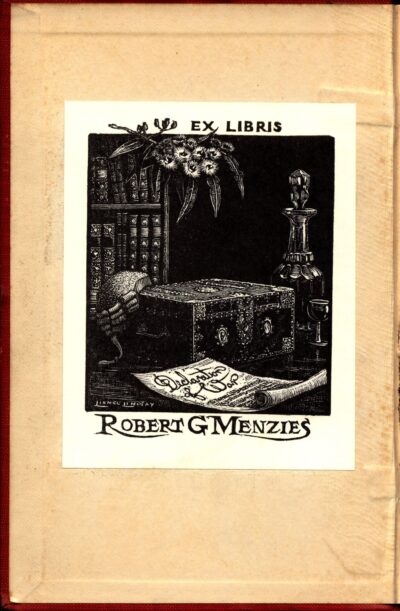

The inscription on Menzies’s copy of De Republica Anglorum indicates that he purchased the book while working as a Barrister-at-Law in Selbourne Chambers. The book deals with important legal matters, particularly as in Smith’s day Parliament functioned as the highest court in England. However, considering the book’s emphasis on political processes, we might imagine that Menzies may have been inspired to acquire a copy shortly before or after he was elected to Victorian Parliament for the first time in 1928 (Menzies deliberately ran for the Legislative Council at the beginning of his political career, because it was then only a part-time commitment that allowed him to keep up his legal practice). In that case, the book is an artefact of the lengths to which Menzies went to understand parliamentary institutions and forms from their historical roots. This study would pay off in Menzies’s great mastery of parliamentary procedure and tradition, and also be reflected in the immense respect he developed for the institution.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.