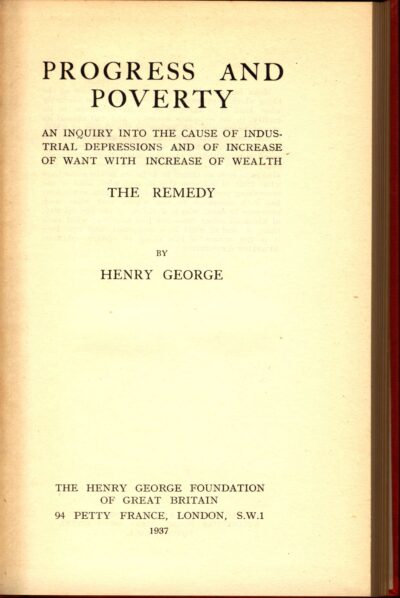

Henry George, Progress and Poverty: The Remedy (1937)

Henry George was a notable American social reformer and political economist who was once highly influential in Australian politics. Touring Australia in 1890, his political theories had a major impact on the early Labor Party and the contemporary Free Trade movement. For a time, his books outsold those of better remembered political thinkers like John Stuart Mill.

George was born on 2 September 1839 in Philadelphia. Brought up in a puritanical family George received a solid education but left high school after five months to become a messenger boy and then a clerk. Becoming a foremast boy at age 15, in 1855 he sailed for Melbourne in the crew of the Hindoo, went on to India and then back to America in April 1856. He finally settled in San Francisco where tried his hand at gold-prospecting and then worked as a typesetter. He joined the Methodists and on 3 December 1861 married Annie Corsina, who had been born in Sydney. Irregular employment kept the couple in relative poverty until George became managing editor of the San Francisco Times in 1866, using the platform to take on major social issues.

Originally published in 1879, Progress and Poverty was George’s seminal work, and it sought to explain why the great material progress the United States had experienced during the 19th century had failed to dramatically raise living standards for ordinary people. His conclusion was that most of the newly created wealth had been syphoned off by landowners, who increased the price of land faster than wealth was produced, and that this process was particularly acute in rapidly industrialising cities.

The book offered a utopian solution to the entrenched wealth and privilege of property owners through the implementation of a ‘single tax’ on the unimproved value of land. This tax was meant to replace all other forms of taxation, and would attack institutionalised wealth while leaving others free from the burden of the costs of government. The fact that the tax was on the ‘unimproved’ value was meant to encourage people to continue to develop their land while punishing those who lived off the ‘unearned increment’ that was derived through ownership and inflation rather than work. The tax was therefore meant to curb land speculation and tax city properties, whose value was derived from their location, more than rural farm properties whose value was derived from what was produced on them. George wanted to use the tax to ‘appropriate rent’; hence land taxation was a roundabout way of achieving a pseudo nationalisation of land – something which George admitted would be politically impossible to achieve in a direct fashion.

At face value, George’s philosophy sounds socialist and revolutionary, however there were elements of the ‘single tax’ which attracted some classical liberals. These included having a somewhat restrained overall level of taxation and therefore scope for government, and encouraging free enterprise and individual initiative by never penalising the improvement of land or any form of profit creation that was not based on land. George was not an opponent of capitalism, and wanted to ‘increase the earnings of capital’ and ‘afford free scope to human powers’. George was against all forms of tariffs as they increased the costs for consumers and particularly the poor.

While George’s influence in Australia peaked during the 1890s depression, it never truly died, and in 2022 a Melbourne based organisation is hosting what it claims to be the 131st ‘Annual Henry George Commemorative Dinner and Adress’.

In the Menzies Era, George’s theories were the inspiration behind the Henry George Justice Party. This was a significant minor party which contested Senate elections in Victoria in 1949 and throughout the 1950s, and its emergence seems to have been tied to the introduction of proportional representation which has since seen a large number of minor parties enter the Senate. The party was thus a notable trailblazer and while their candidates never won a seat, they often received near 1% of the vote and their opinions received significant newspaper coverage.

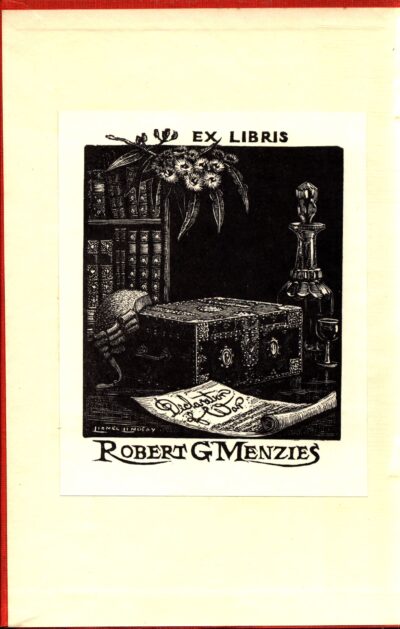

Menzies’s copy of Progress and Poverty shows that he took them seriously enough to try to understand their arguments. It also serves as an artefact of a rather eccentric but enduring strand in Australian political history.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.