Edmund Burke, Selections from His Political Writings and Speeches [n.d.]

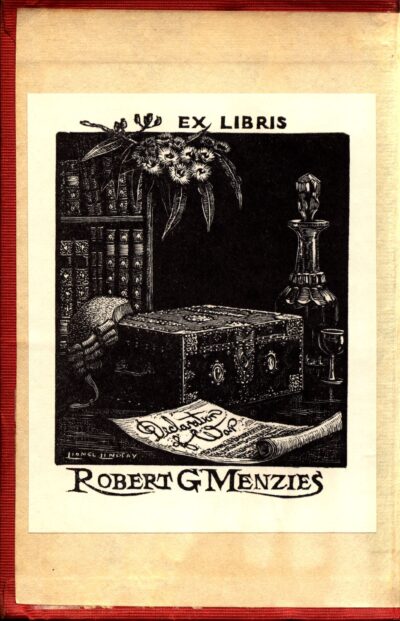

Edmund Burke was an eighteenth-century British statesman, parliamentarian and political theorist whose writings remain central to modern political conservatism (though notably Burke was a Whig rather than a Tory, and it was often freedom which he sought to safeguard through respect for tradition). For Robert Menzies Burke was a central intellectual influence, whom he described as ‘the greatest of all practical philosophers’.

Born in Dublin in 1729 as the son of a solicitor, Burke attended Trinity College before going to study law at Middle Temple. Burke lost interest in pursuing a legal career however, and would effectively drop out, spending some years in obscurity wandering around England and France before producing his first written work A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful.

Once he had developed a reputation as a writer, Burke was able to lean on connections with a number of leading Whig figures to enter Parliament in 1765. He was soon weighing in on the constitutional controversy which was then raging over George III’s attempt to choose his ministry. Believing the King was betraying the spirit of Britain’s unwritten Constitution, Burke advocated for Parliamentary control of the ministry, a key component of what is known as Responsible Government. This led to the publication of ‘Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents’ which contained Burke’s famous definition of a political party, which Menzies would quote on multiple occasions to justify both the party system (as opposed to voting for independents) and the formation of the Liberal Party:

‘Party is a body of men united for promoting by their joint endeavours the national interest, upon some particular principle in which they are all agreed… Men thinking freely, will, in particular instances, think differently. But still as the greater part of the measures which arise in the course of public business are related to, or dependent on, some great, leading general principles in government, a man must be peculiarly unfortunate in the choice of his political company if he does not agree with them at least nine times in ten.’

For Menzies, party was the mechanism through which the people could directly influence policy by choosing the government. Likewise, Menzies adopted Burke’s conception of the role of a Member of Parliament, who was not to be a mere delegate bowing to every whim of their electorate, but was instead tasked with independent thinking and bringing their ‘matured judgment’ to each individual issue.

Burke was a leading commentator on two of the greatest political developments of his time, the American Revolution and the French Revolution. Burke supported the former, because he believed the Americans were fighting for tangible British rights to which history and inheritance entitled them, but he rejected the latter because it attempted to wipe the slate clean and destroy all existing institutions in the name of a utopian new beginning. To Burke this was an anathema, because historical institutions carried with them the wisdom of multiple generations which was greater than what one individual could reason from first principles:

‘The very idea of the fabrication of a new government is enough to fill us with disgust and horror. We wished at the period of the [Glorious] Revolution, and do now wish, to derive all we possess as an inheritance from our forefathers.’

Menzies likewise greatly admired the historical roots of British democracy, which provided ballast and allowed for ongoing success. He was sceptical of the idea that democracy could be imposed upon a country without this cultural element, and while he believed in progress, he saw that it was the historical continuity of the parliamentary system which allowed reform to be consolidated. Echoing Burke’s description of a partnership between the living, the dead and those who are yet to be born, Menzies would say that ‘It’s only when we realise that we are part of a great procession, that we’re not just here today and gone tomorrow, that we draw strength from the past and we may transmit some strength to the future’.

All of these issues are covered in Selections from His Political Writings and Speeches, which is made up of three sections: ‘The Governance of Britain’, ‘America and the Colonies’, and ‘The French Revolution’. Beyond this book, Burke features heavily in the Menzies Collection as part of books of collected prose and quotations, in which his passages are frequently underlined. For example, in Men and Affairs Menzies has noted Burke saying:

‘Men are qualified for civil liberty, in exact proportion to their disposition to put moral chains upon their appetites, in proportion as their love of justice is above their rapacity, in proportion as their soundness and sobriety of understanding is above their vanity and presumption’.

Such a passage speaks deeply to Menzies’s conception of democracy, which focused heavily on the duties of the individual, as opposed to their entitlements.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.