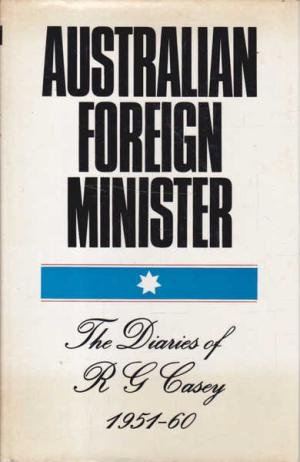

T.B. Miller (ed), Australian Foreign Minister: The Diaries of R.G. Casey 1951-1960 (1972)

Richard Gavin Gardiner Casey (also known as Lord Casey of Berwick) was an engineer, diplomat, politician, governor and governor-general, who remains the second longest-serving External Affairs/Foreign Minister in Australian Political History.

Casey was born in 1890 as the son of successful Queensland pastoralist and politician Richard Gardiner Casey. In 1893 the family moved to Melbourne, as Richard Senior took up a role as a company director and bought a mansion in South Yarra dubbed ‘Shipley House’. The younger Casey thus had a highly privileged, albeit somewhat emotionally neglectful, childhood before studying engineering at the University of Melbourne and mechanical sciences at Trinity College, Cambridge.

With the outbreak of war in 1914 Casey joined the AIF as an officer, and he had a distinguished period of service which included a posting as staff captain at Gallipoli. With the death of Richard Senior in 1919, Casey succeeded his father’s positions on several company boards and for a time envisaged himself becoming an innovative tycoon in the manner of Henry Ford. His career- path gradually shifted as Prime Minister Stanley Bruce convinced him to join the Commonwealth Public Service and go to London as Australia’s liaison officer.

With the election of a Labor Government in 1929, Casey returned home and decided to enter politics, winning the Victorian seat of Corio for the UAP. ‘An indifferent orator, shy, stiff, unmoved by parliamentary ritual…Casey was poorly equipped for politics’, but he nevertheless became Federal Treasurer and was considered a rival to Robert Menzies when it came to succeeding Joseph Lyons. In the event, Casey got less votes in the leadership ballot than the 76-year-old Billy Hughes, alienating Menzies less as a threat in his own right than for trying to convince Bruce to re-enter politics.

As Prime Minister Menzies shifted Casey from the Treasury to the new Department of Development and Supply before appointing him as Australia’s first Minister to Washington in 1940. There he displayed a flair for diplomacy, having fruitful talks with FDR on a number of occasions, and this set him down a diplomatic path that would lead to postings as British Minister of State in the Middle East and then Governor of Bengal (both appointments being made by Winston Churchill).

After the expiry of his term as Governor, Casey looked to return to Federal Politics to once again challenge Menzies for the leadership of the non-Labor forces, but failing to secure preselection in time for the 1946 election he instead became Federal President for the Liberal Party before returning to Parliament in 1949 as a member of the Menzies Government. He returned to his old post of supply and development (soon renamed national development) before Menzies decided to take advantage of Casey’s diplomatic experience by appointing him Minister for External Affairs in 1951. Considering the turbulent relationship between the two men, this position had the added benefit that Casey would often be out of the country, lessening the chance for personal friction.

Edited by ANU academic Thomas Millar, Casey’s published diaries reveal much about Australian foreign policy and the decision making that went into it during a number of key moments in the Menzies/Cold War era. For example, the book reveals that Casey had an erroneous skepticism about the economic future of Japan, and that the Government’s push for a controversial Commerce Agreement was by no means a guaranteed success. Significantly, Casey believed that ANZUS had a political importance for the Government that was perhaps more significant than its military importance as a working defence treaty. The diary also reveals that Casey held strong views in favour of recognising the Chinese Communist Government in the 1950s (almost two decades before Whitlam would do so).

A firm advocate of Australia’s engagement with Asia, while in Jakarta in 1952, Casey wrote that: ‘I am developing the feeling more and more that we, in Australia, are living in a fool’s paradise of ignorance about the East. It is extremely difficult to get a realistic discussion in Australia about affairs in the East, in matters that vitally affect Australia’s future. This is humiliating but true.’

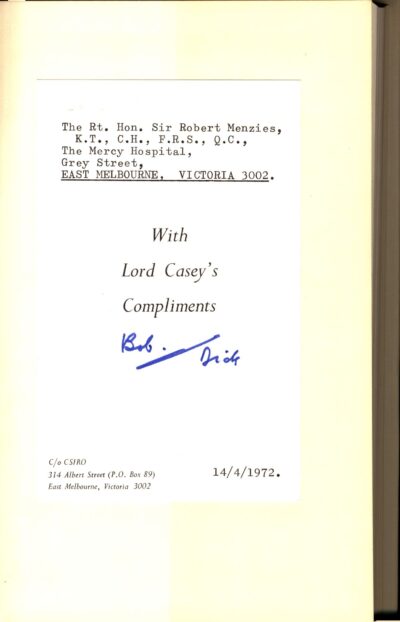

Casey’s limited presence in the Menzies Collection attests to the frosty nature of the relationship between the two men as it has generally been described, but also that it had a thawing later in life. There are three books gifted and inscribed by Casey in the Collection, and while they admittedly all come from the period after his retirement as Prime Minister, the language used in them can be quite warm and personal. The copy of Australian Foreign Minister has a particular poignancy, given that it was sent to Menzies while he was in hospital recovering from a stroke in 1972. Inscribed by ‘Dick’ it includes a yellow slip of paper identifying the section on the Suez Crisis, an issue on which the views of the Prime Minister and the relevant Minister had greatly diverged.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.