Edward Hallett Carr, Conditions of Peace (1942)

Edward Hallett Carr was a British political scientist and international relations theorist who wrote extensively and highly sympathetically on the Soviet Union.

Born to a middle-class London family with an acute interest in politics, Carr won a scholarship to study at Trinity College Cambridge. Upon graduating in 1916 he joined the Foreign Office, where he would be involved in the Versailles peace treaty negotiations and clash with War Secretary Winston Churchill over Britain’s approach to the Russian Civil War. Initially spurred by work responsibilities, Carr’s study of Russian affairs and appointment to the British embassy in Riga exposed him to the tenets of Marxism and he gradually came to support a highly interventionist role for the state.

By 1936 Carr had been appointed as Woodrow Wilson Professor of International Politics at the University College of Wales, and established a name for himself as one of the leading commentators on foreign relations issues. While critical of Hitler, through the 1930s Carr was a strong supporter of appeasement as the only realistic position for European nations to take, and he was quick to denounce Churchill as an opportunist for his opposition to the policy. Forced by events to move away from this position, Carr nevertheless remained something of a ‘realist’ and would spend much of the war arguing that the USSR had a right to a sphere of influence in Eastern Europe and that Britain should emulate her economic policy.

Published in the middle of the conflict, Conditions of Peace is a socialist tract that argues that the war had been caused by economic factors and that the only way to prevent its repetition was via an economic revolution. According to the author, the war had been predicated on three 19th century ideals that were outmoded and needed abandoning. These included not just laissez faire, but also the values of liberal democracy and national determination.

Carr delineated between countries like Britain and France who were ‘satisfied powers’ who had been happy with maintaining a status quo stuck in the past, and the ‘dissatisfied powers’ like Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia who had seized all initiative in the interwar years. Along with the advent of socialism and the ‘planned economy’, Carr sought what he called a ‘European Planning Authority’, which presaged the European Union in its economic coordination and deliberate breaking down of national barriers. The book was highly controversial for suggesting a magnanimous peace with Germany (one which would not repeat the mistakes of Versailles), and that the British Empire should give up all her colonies and hand them over to an international commission.

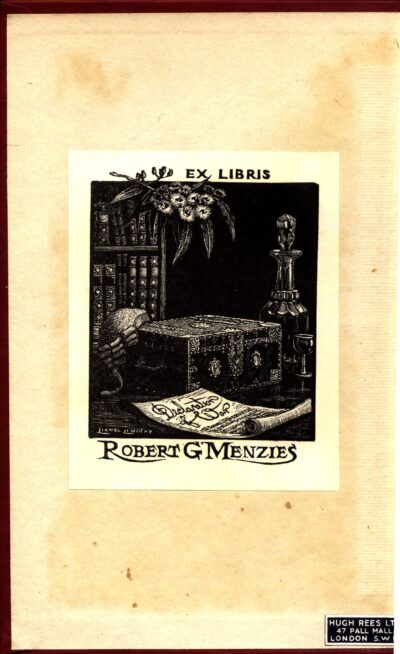

Much of the thesis of Conditions for Peace is based on ideas that we can expect Menzies to have vehemently disagreed with, but the fact that he appears to have thoroughly studied the book shows that Menzies was open to engaging with a wide range of perspectives as he grappled with the fundamental issue of what a post war world would look like. In Menzies’s radio broadcasts from this time, we are able to see that he was genuinely considering such radical ideas as the curtailment of national sovereignty in the name of global security.

While he mostly moved on from his flirtation with such novelties, in a more tangible and permanent manner Menzies appears to have been influenced by Carr’s arguments about the vulnerability of small states. With a pencil line in the margin on page 55, Menzies has highlighted the following passage in the book:

‘Small states can no longer balance themselves in dignified security on the tight-rope of neutrality. Still less can they rely on an indeterminate system of collective security which leaves open the identity of the future enemy and the future ally. The small country can survive only by seeking permanent association with a Great Power.’

Such a line of thinking is very in keeping with Menzies’s approach to foreign policy, which sought to maintain strong relationships with ‘great and powerful friends’ rather than relying too heavily on international organisations like the United Nations.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.