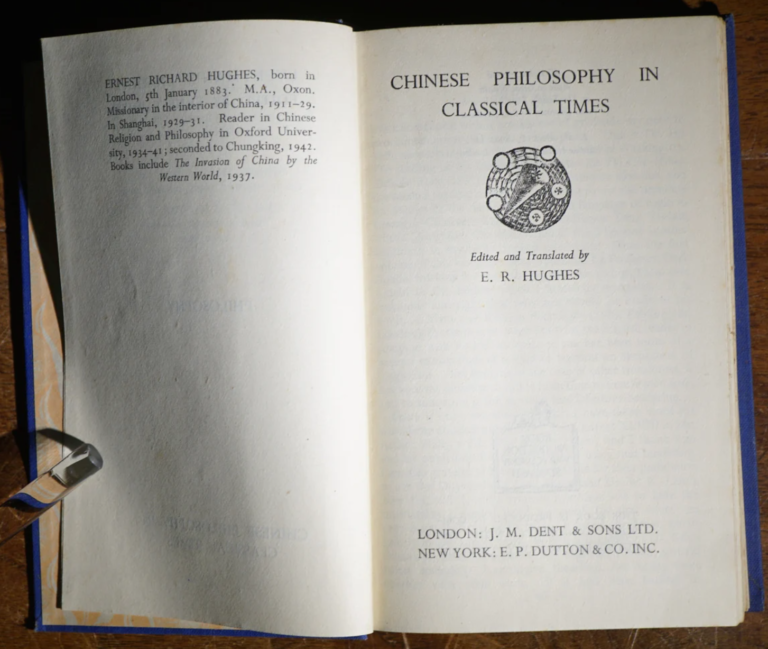

E.R. Hughes, Chinese Philosophy in Classical Times (1942)

Ernest Richard Hughes was an eminent Sinologist who published numerous books on Chinese history, culture and philosophy.

Born in 1883, Hughes studied at Oxford before joining the London Missionary Society. His missionary work took him to China in 1911, and Hughes quickly fell in love with the place, living there for over two decades. At the end of 1933, Hughes returned to England to be appointed Reader in Chinese Philosophy and Religion at his alma mater. At Oxford, Hughes was responsible for the introduction of an Honours Degree in Chinese, and he also travelled around the United States doing tremendous work in educating the English-speaking world to better understand China and her people.

Chinese Philosophy in Classical Times provides a history of the evolution of Chinese thought while offering ground-breaking English translations of extracts from a myriad of classical texts. Its introduction explains that:

‘There is something particularly appropriate about an “Everyman” volume on Chinese Philosophy, for the Chinese people and their tradition have been impregnated with a sense of Everyman. It is true that there has been, and still is to-day, a great deal of virtuosity in their approach to matters of learning; a Chinese scholar can be ineffably highbrow. But from a quite early date in Chinese history most thinkers and scholars never succeeded in forgetting that the ordinary man, and in particular the peasant, is a vitally important member of the Great Society. So also with the exquisite art of painting in China, and with that other great art which the modern West tends to ignore, that of ritual in daily life; the plain man in the plainness of his humdrum life has always claimed in China a good share of the expert’s attention. It is the Chinese sense of a common humanity; and in spite of all the inhumanities which have been perpetrated by proud aristocrats and conscienceless money-makers, this sense continued to bear fruit, has indeed been an integral part of that common sense and matter-of-factness for which the Chinese people have become famous throughout the world.’

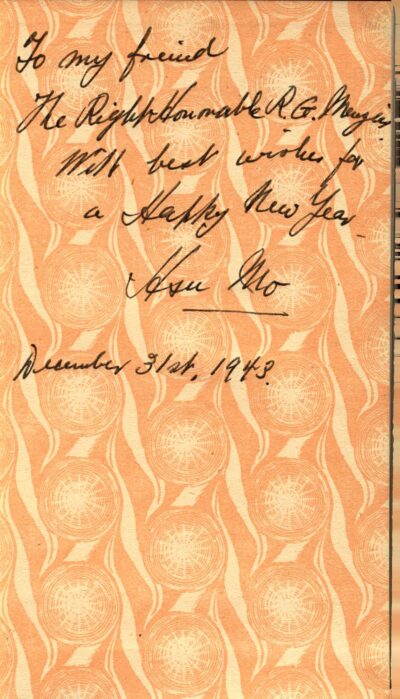

The Menzies Collection contains two copies of Chinese Philosophy in Classical Times, the more interesting one being a gift from Chinese Ambassador Hsu Mo dated 31 December 1943. Hsu Mo was a remarkable politician and diplomat. A graduate of George Washington University, he served as deputy foreign minister for the Chinese Nationalist Government and was later heavily involved in the United Nations and the International Court of Justice (on which he served as a judge).

He was appointed as China’s first Minister to Australia in July 1941, while Menzies was Prime Minister. Menzies had enquired about a formal exchange of Ministers with China earlier in the year, and after seeking permission from the United Kingdom, he appointed Frederic Eggleston as Australia’s first Minister to China (the position was first offered to former Prime Minister James Scullin, but he declined). At the time China was struggling virtually alone in her war of resistance against Japanese aggression, but the prospect that that conflict would soon conflate with the existing global confrontation loomed large. Australia’s first overseas diplomatic missions were established by Menzies in Washington and Tokyo in 1940, this was the third.

Hsu Mo arrived in Sydney to a grand public welcome and crowds of local Chinese waving the flag of the Republic of China. Hsu told reporters that China and Australia were ‘in the same hemisphere, and to a great extent we share the same perils.’ Hsu was very well respected and eloquent, making a great impact in an Australia where existing racial prejudices had been heightened by the war. His speeches were frequently reported by Australian newspapers and he even delivered a number of radio broadcasts to directly explain China’s plight and resilience to the Australian people. The admiration he earned from his efforts led to him being granted an honorary Doctorate of Laws from the University of Melbourne in March 1943, and the pressmen were very diligent in always referring to ‘Dr’ Hsu Mo.

The stereotyped image of Menzies as an Anglophile might lead to an assumption that he would be uninterested in Chinese philosophy of the type contained within Hughes’s book. However, the truth of the matter is that Menzies actively sought to engage not just diplomatically but also intellectually with Australia’s ‘near north’. Indeed, his Forgotten People series of radio broadcasts from around the same time he received Hsu Mo’s gift quote from Confucius and other Eastern thinkers on a few occasions (though it is unclear if this was based on Chinese Philosophy in Classical Times or another work in the collection called The 4 Books: Confucian Analects).

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.