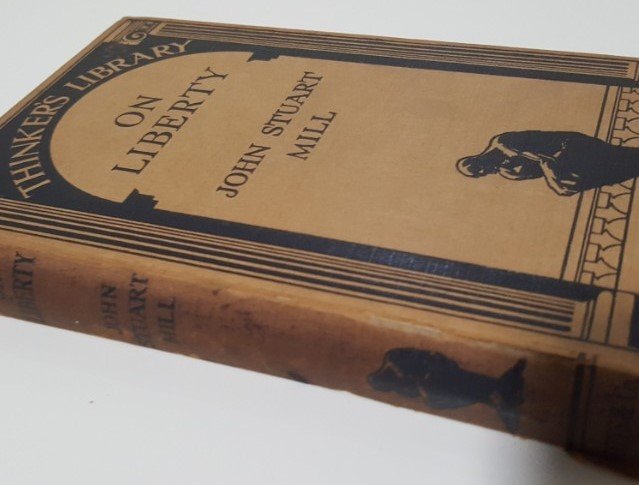

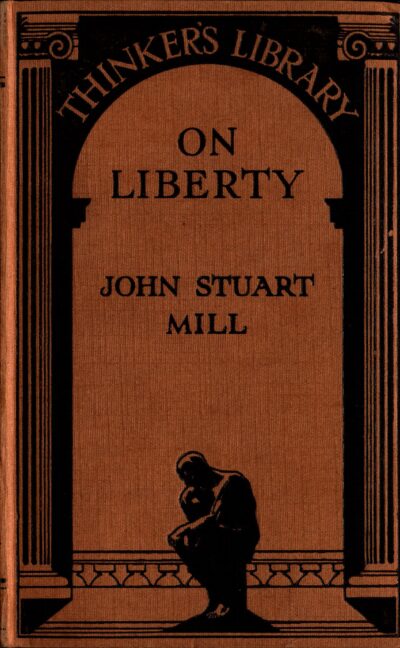

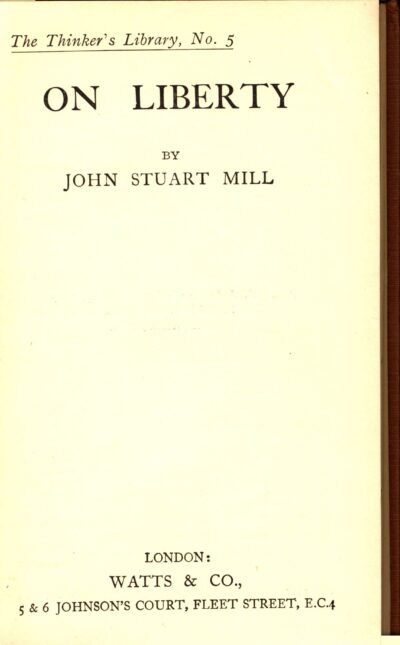

John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1932 Thinker’s Library Edition)

John Stuart Mill was one of the most influential political philosophers of the nineteenth century and he continues to have an enormous contemporary relevance. It is often said of the Liberal Party of Australia that it is the party of Mill and (Edmund) Burke, and there is ample evidence that its founder was powerfully influenced by both figures.

Born as the eldest son of British historian, economist and philosopher James Mill in 1806, John Stuart had the advantage of a deep classical education that featured Xenophon, Herodotus, Diogenes, Isocrates, Plato and Aristotle. He developed an assiduous and inquisitive mind, and as a young man began writing in various newspapers and journals. He suffered a mental breakdown in 1826, but recovered to become a constant figure at the London Debating Society, editor of The London Review, and later serve as a Member of Parliament.

Carrying over from his childhood, Mill was a man of eclectic intellectual interests. He was heavily influenced by the utilitarian philosophy of Jeremy Bentham, was regarded as an expert on political economy, advocated for the emancipation of women, and in his later years dabbled with ideas surrounding property which bordered on socialism. But arguably his greatest impact would be made as a proponent of liberalism and individual liberty, and his greatest work in this vein was On Liberty originally published in 1859 – which argues that the only legitimate reason to interfere with an individual’s liberty is to prevent harm to others and that freedom, and particularly the free exchange of ideas, are necessary for progress.

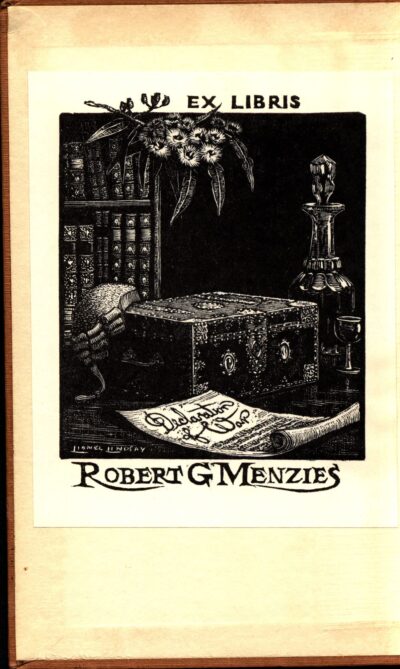

If there is one thing that the Menzies Collection makes clear, it is that its former owner was a discerning reader, and he would not have agreed with Mill on everything. While he believed in liberalism and the equality of men and women, Menzies was a fierce critic of both utilitarianism and socialism, and it is notable that the only one of Mill’s works which survives in the collection is On Liberty. Nevertheless, it is a copy which clearly saw extensive use.

Menzies believed that the work had a particular importance in his contemporary context which had seen the individual crushed by totalitarian regimes like fascism and communism, and in which the future of democracy seemed to be imperilled. He discussed On Liberty in detail during a Forgotten People radio broadcast on ‘Freedom of Speech and Expression’ delivered on 19 June 1942, which is highly illuminating in demonstrating how Menzies interpreted the work:

‘Now, why is this freedom [of speech] of real importance to humanity? The answer is that what appears to be today’s truth is frequently tomorrow’s error. There is nothing absolute about the truth. It is elusive. In the old phrase, “it lies at the bottom of a deep well”. It is hard to come at. So few of us have objective minds – detached minds – and what we conceive to be the truth is very often coloured or distorted by our own passions or interests or prejudices. Hence, if truth is to emerge and in the long run be triumphant, the process of free debate – the untrammelled clash of opinion – must go on.

There are fascist tendencies in all countries – a sort of latent tyranny. And they exist, be it remembered, in radical as well as in conservative quarters…

Many of you will recall John Stuart Mill’s famous essay on Liberty, which was published eighty-three years ago, but is still full of freshness and truth. In the course of that essay Mill stated many principles, four of which I should like to put to you in his own words. First:

“There is a limit to the legitimate interference of collective opinion with individual independence: and to find that limit, and maintain it against encroachment, is as indispensable to a good condition of human affairs as protection against political despotism.”

What is being pointed to in that passage is the easily forgotten truth that the despotism of a majority may be just as bad as the despotism of one man. Public opinion in a reasonable educated community will, I believe, in the long run over a term of years, tend to be sound and just; but public day-to-day opinion, which must frequently be ill-informed, is quite capable of being not only wrong, but so extravagant as to be unjust and oppressive.

My second passage from Mill is this:

“The principle is, that the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.”

Here again we have a pregnant truth. It is a good rule, not only of common law but of social morality, that we must so use our own as not to injure others. The man who claims too much aggressive liberty for himself may be getting it at the expense of somebody else. Liberty is for all, not for some.

Mill next says:

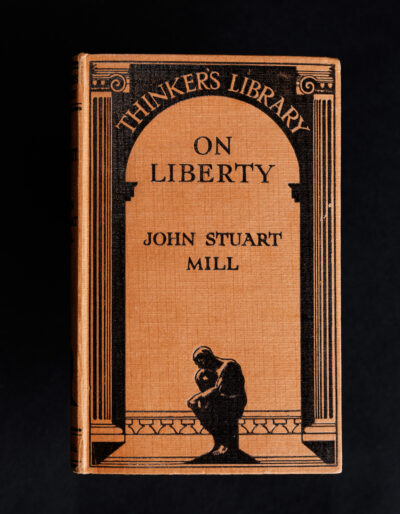

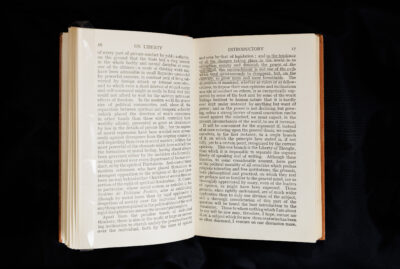

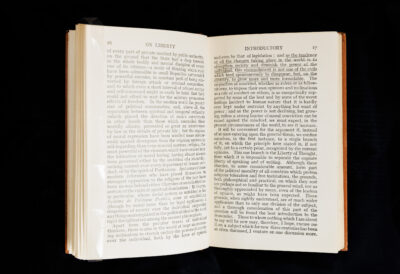

“As the tendency of all changes taking place in the world is to strengthen society and diminish the power of the individual, this encroachment is not one of the evils which tend spontaneously to disappear, but, on the contrary, to grow more and more formidable.”

[Notably this passage is underlined in Menzies’s copy of On Liberty, providing a tangible connection between the physical artefact and this speech]I find this passage particularly illuminating. Fascism and the Nazi movement are both based on social philosophy which elevates the all-powerful State and makes the rights of the individual, not matters of inherent dignity but matters merely of concession by the State. Each says to the ordinary citizen, “Your rights are not those you were born with, but those which of our kindness we allow you.” It is good to be reminded by Mill that this tendency is not confined to any one country. As the organisation of society becomes more complex we must be increasingly vigilant for the freedom of our minds and spirits.

My final passage from Mill is this:

“Complete liberty of contradicting and disproving our opinion is the very condition which justifies us in assuming its truth for purposes of action: and on no other terms can a being with human faculties have any rational assurance of being right.”

In other words, it is a poorly founded and weakly held belief which cannot resist the onset of another man’s critical mind.

There are, without doubt, limits on all these matters in time of war. When the battle is on, when nations are in a death struggle with other nations, the supremacy of the national security is clear and undoubted. That is the whole justification for wartime censorship, as well as the element that sets limits to it.

But even in time of war we must watch these things. You will agree that I speak as one with some practical – occasionally painful – experience, when I say that the arrow of the critic is never pleasant and is sometimes poisoned. Much criticism is acutely partisan or actually unjust. But every man engaged in public affairs must sustain it with a good courage and a cheerful heart. He may, if he can, confute his critic, but he must not suppress him. Power is apt to produce a kind of drunkenness, and it needs the cold douche of the critic to correct it.’

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.