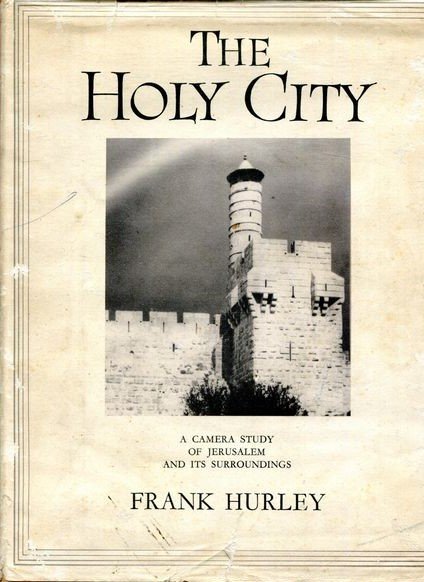

Frank Hurley, The Holy City: A Camera Study of Jerusalem and its Surroundings (1949)

James Francis (Frank) Hurley was a famous Australian adventurer, photographer, and filmmaker, noted for everything from exploring the South Pole to filming the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. His ADB entry documents that ‘for three decades he inspired Australian film makers and photographers and was the most powerful force to shape Australian documentary film before World War II’.

Born in Glebe in 1885 as the son of a printer and union official, at the age of thirteen Hurley ran away from Glebe Public School and ended up spending two years working in a steel mill. Returning home, Hurley studied by night at the local technical school and the University of Sydney, taking up an apprenticeship as an electrical fitter and instrument maker in the lighting branch of the New South Wales Telegraphic Department. Somewhere in all of this Hurley developed an interest in photography. He bought a Kodak box camera for 15 shillings and took up a new career in the postcard industry, earning a reputation for risking his life to take spectacular shots, including a famous picture taken from in front of an oncoming train.

This fearlessness and dedication to his craft made Hurley the perfect fit to become the official photographer for Douglas Mawson’s Australasian Antarctic Expedition. Hurley was a high spirited and popular member of the team on what proved to be a harrowing and arduous undertaking, which took the life of explorer Belgrave Ninnis. Hurley collated the footage he took on the journey to produce his first documentary film, Home of the Blizzard.

On the back of new found fame, Hurley was commissioned to film an exploration of northern Australia, and then to join another renowned explorer Ernest Shackleton on his Antarctic mission. Hurley was the only member of the team that Shackleton had never met. Recruited on the strength of his work, he more than lived up to expectations producing iconic photographs of the ship Endurance being destroyed by pack ice and gripping images of the struggle for survival faced by Shackleton’s men. The experience once again became a film, this time called In the Grip of Polar Ice.

The expedition occurred concurrently with the first years of the Great War, and with its competition in 1917 Hurley joined the Australian Imperial Force as an official photographer with the rank of honorary captain. With characteristic disregard for his own personal safety, Hurley took close footage of exploding shells, but he ultimately grew frustrated at the high levels of censorship he faced trying to document what was really happening on the Western Front. As a result he resigned, but rather than leaving the army he was sent to the Middle East where he chronicled many of the triumphs of the Australian Light Horse and even had his first experience of flying.

This led to Hurley taking some ground-breaking pictures of Australia from the air in the immediate post-war period, before spending several years filming in Papua, Dutch New Guinea and the Torres Strait. This led to several commercially successful films, though ones which were coloured by the prejudices and stereotypes of their day, so much so that Papuan administrator Hubert Murray ended up clashing with Hurley over the negative publicity resulting from vivid tales of ‘head-hunting’ and the like.

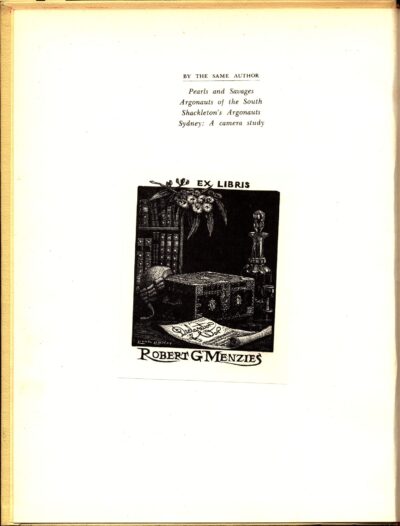

When the Second World War broke out, Hurley once again joined the AIF in a photographic capacity and made his way to the Middle East which is where he met and befriended Robert Menzies. As wartime prime minister in early 1941, Menzies spent 10 days in the Middle East inspecting Australian troops on his way to London. There he would endure the ‘blitz’ and what seemed to be the looming inevitability of a German invasion, grievous circumstances which made his task of convincing Churchill to give more Allied resources to the Pacific in order to protect Australia almost impossible.

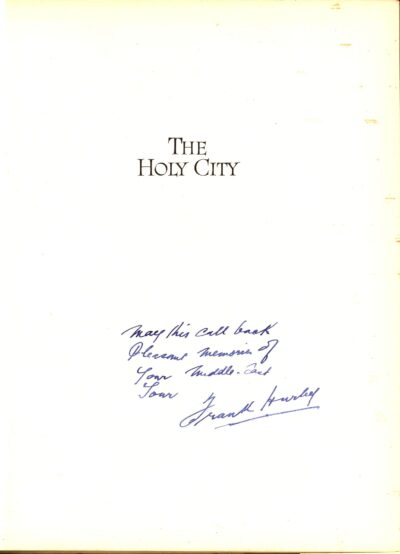

It was as a memento of these ‘dark and hurrying days’ that Hurley sent Menzies a copy of The Holy City: A Camera Study of the Holy City and its Borderlands, with an inscription saying ‘May this call back pleasant memories of your Middle East tour’. The Menzies Collection also contains a signed copy of Shackleton’s Argonauts, as well as a copy of Hurley’s Western Australia: A Camera Study – a significant representation highlighting Hurley’s cultural significance.

When giving a speech at the opening of the Mawson Institute at the University of Adelaide in 1961, Menzies would give his personal recollection of a comical incident he shared with Hurley in the Middle East:

‘In 1941, in about February, I was in the Middle East and went with Sir Thomas Blamey to Benghazi, the day after the battle of Benghazi – it wasn’t a Polar region we were in, I can assure you – and with loving care for a Prime Minister, something I have seldom experienced, we flew in a tolerably fast plane and we were escorted, believe it or not, by a couple of fighter aircraft.

But the following day we flew back from a place called Barce in a biplane called a Valencia. Nobody could remember when it was built, but it was regarded as almost the equivalent of a T-model Ford. It had two flapping wings, and it had those windows made of what laymen like myself call “mica” but might be anything, and they were warped and twisted by the weather and by old age. As soon as we made a little height alongside the mountain range that runs there, it got colder and colder, and the blast came in on us. We were all sitting in mangers – that’s all I can describe them as – on the side of this plane. The wintry blast came in; we had been provided with reading matter of a good solid kind like London Punch, and other journals of that kind. So far as I was concerned I grabbed as many as I could and tucked them inside my trousers. And then when a very respectful young Air Force lad came along and said, “Would you like a rug?” I said, “Certainly bring me two”. (Laughter) And he brought me two blankets and I ensconced myself in them and so did other people.

Finally we got out at a windswept aerodrome called El Aden, which some of you know, so stiff with the cold that it was hard to walk. It was 400 yards across to the airport building and to a really nourishing drink – 400 yards. Out got Frank Hurley. He had been travelling a little farther back in the plane than me. He was in uniform, and when he got out he could hardly walk. So I said, “My dear Hurley, it’s all right for a soft civilian like me to be frozen, but a polar man like you…” He said, “That’s the trouble, that’s the trouble. When this boy came along to me and seeing my grey hair, and being innocent of my lack of rank said to me, ‘Sir, would you like a blanket or two?’ I started to say ‘Yes’ and then my eye caught my polar ribbons and I thought, ‘I can’t let the side down’. I said, ‘No, no thank you very much, no thank you very much. On the whole I think it’s rather stuffy”. (Laughter) And so, even more than I did, he limped away in the direction of that distant, but tantalising, whisky, as we hoped, in the Officers’ building.’

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.