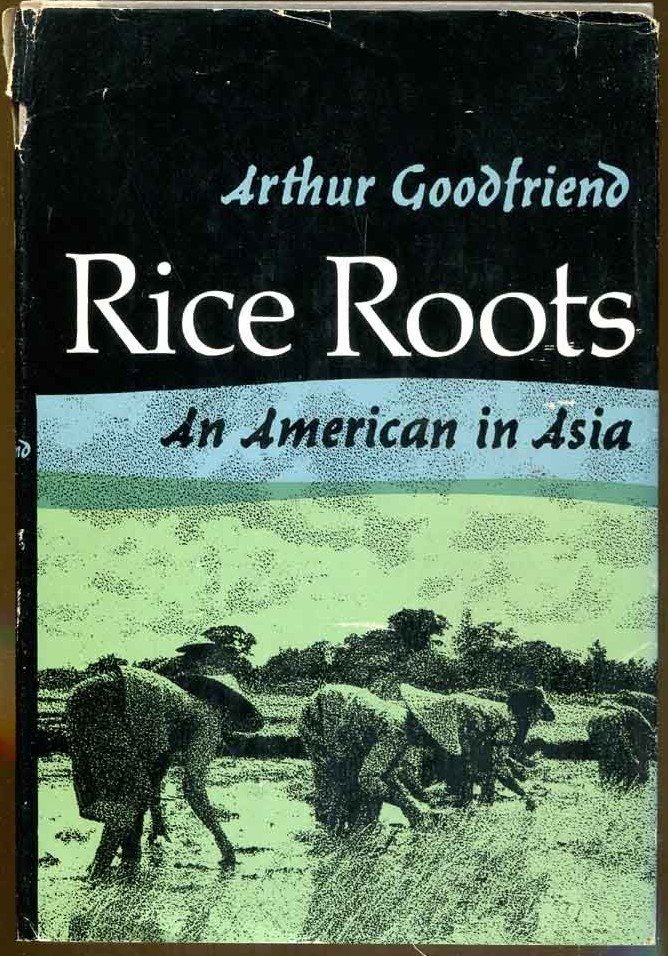

Arthur Goodfriend, Rice Roots (1958)

Arthur Goodfriend was an American journalist, diplomat and academic who wrote extensively about how the United States could and should better understand the nations of Asia in a Cold War context.

During World War Two Goodfriend served in Europe as the editor of the U.S. Army’s newspaper Stars and Stripes. After VE Day, he was transferred to the Pacific theatre and set up shop in Chungking China, where he had the ‘dubious distinction’ of being one of the first American soldiers to be captured by the Chinese Communist Army. In this context, his journalism became focused on the political turmoil Asia experienced in the aftermath of the War and with the reluctant withdrawal of its former colonial masters. He wanted to understand the region on its own terms, and use this as the basis for ensuring that the countries of Asia did not fall to the domino theory of communist advance.

Rice Roots is focused on Indonesia, a nation which had recently emerged from Dutch rule and which at the time had one of the largest communist parties in the region. Goodfriend spent years in the country, living in the town of Solo with his family, conducting research for the book. He argued that Indonesia held the key to comprehending the region, for ‘Indonesia and its people are an archetype of Asia. Here geography and history have fused almost every Asian strain. Here are Malayan blood, Buddhist art, Hindu scripture, Islam’s God. Here are every Asian woe and every Asian hope. Here are Asia’s “teeming masses” – poor, proud, and infinitely powerful. Here, incarnate, are Asia’s rice roots.’

He set out his aim and thesis in clear terms in the first few pages:

‘Dollars and diplomacy might reach Asian governments, but they were not reaching the people. Much that we were doing was far removed from their grievances, anxieties, needs and hopes. Only by getting down in the dirt and working beside them, on equal terms, toward goals of the people understood and cherished, could we win their friendship. Only by knowing their goals and identifying our own with theirs could we persuade Asians to join us in their achievement. Only Asians with something to defend, and the will to defend it, could save Asia. Billions spent in Asia to reshape it in America’s image would be wasted. But pennies spent to strengthen Asia’s own indigenous institutions, to build improvements the people themselves could pay for and maintain, would help create the self-respect, self-reliance, self-confidence indispensable to prosperity, freedom, and peace in Asia. America, in short, should shift its sights from Asia’s leaders, many of them discredited, to Asia’s masses.’

Their follows a personal account of what Goodfriend understood to be the grassroots of the nation, as he travelled around documenting the experiences of ordinary Indonesians and what mattered to them. In doing so he hoped to overcome the ignorance of the American people and destroy the stereotypes they maintained about the ‘teeming masses’ of Asia.

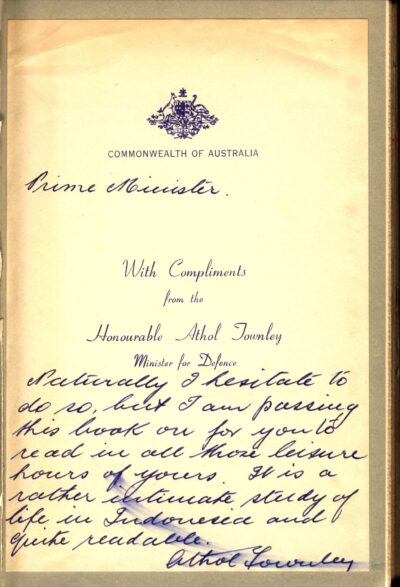

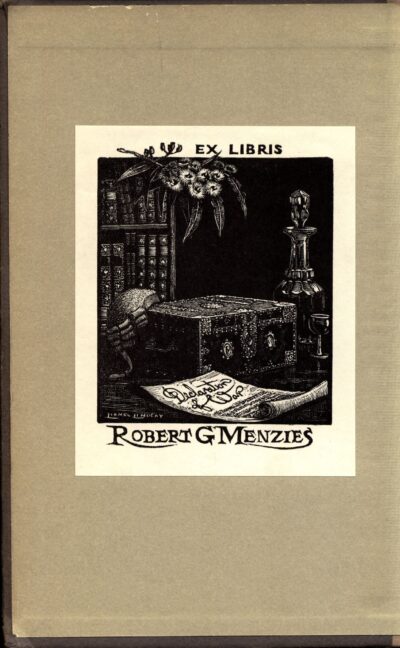

Menzies’s copy of Rice Roots was given to him by Athol Townley, the Defence Minister in the Menzies Government from December 1958 until December 1963. It contains a note fixed to the front endpaper, on which Townley explains ‘Prime Minister. Naturally I hesitate to do so, but I am passing this book on for you to read in all those leisure hours of yours. It is a rather intimate study of life in Indonesia and quite readable.’

The book is recorded to have entered the Commonwealth National Library on 19 November 1958, but when it was gifted to Menzies is unclear. Australia had a strained relationship with Indonesia during much of the Menzies era, and the two countries were frequently on the edge of war over issues like Dutch New Guinea and the Confrontation, the latter of which would see Australian and Indonesian troops secretly fight each other over the creation of the Federation of Malaysia.

Given the constructive nature of the book and the timeline of when Townley was Defence Minister, it would seem that it was gifted during a thawing in the relationship, which saw Menzies become the first Australian Prime Minister to visit Indonesia in late 1959. The book is thus an artefact of a crucial time in Australia-Indonesia relations, during which there was a concerted effort by the Menzies Government to try to foster a friendly relationship with the Indonesian Government and its leader President Sukarno. In this context, the book is evidence of the Menzies Government’s attempt to garner an understanding of Indonesia and its people as Australia’s neighbours to the ‘near north’.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.