Hilary Page, Playtime in the First Five Years (1953)

Hilary (Harry) Fisher Page was an innovative toy creator who pioneered applying child psychology to toy design. During the years 1932 to 1957 he changed the face of the British toy industry and created some of the classic pre-school toys played with by children today. He is now best remembered for patenting the ‘interlocking building brick’, which was adopted and modified to become the ubiquitous LEGO brick.

Born on 20 Aug 1904 in Sanderstead, Surrey, Page showed an interest in making toys and inventing his own games even as a child. His father, who worked in the lumber trade, once bought him two tons of scrap wood from a local sawmill, which supplied Page with the material for years of experimental toy-crafting. When Page was asked years later how he became a professional toymaker he answered that ‘…he had an intelligent father who in his childhood gave him the opportunity to develop his own ideas for making toys.’

After his education was finished Page followed in his father’s footsteps by working in the timber trade for several years. In 1929 he married Norah Harris, a long-time neighbour and in 1932 their only daughter, Jill, was born.

In 1932 Page founded Kiddicraft, a toyshop in Purley, Surrey, with £100. Within a few years Page began to devote serious study to early childhood play, conducting the research that would produce the first edition of Playtime in the First Five Years published in 1938. Page ‘used to spend the whole of every Wednesday in a different nursery school, sitting on the floor and playing with the children, to find out exactly what type of toys would be of the greatest interest to them’.

Page’s book was innovative in seeing toys as educational tools which could be used to encourage development. He explained that ‘preparation for the adult world is daily enhanced, as the child learns many of its laws and lessons through the process of imaginative play. No less important, however, is the embracing refuge offered by playland from the frustration and distresses of reality’.

Page naturally encouraged parents to let their children experiment with carpentry as his father had with him, assuring those that might have safety concerns that after the children learned the lesson of hammering their fingers a few times all danger would pass and they would discover a ‘land of opportunity’ that encouraged imagination and experimentation.

Despite his natural bias towards woodwork, one of the things Page noticed through his careful observations was that children tended to gnaw on the corners of wooden toys, ingesting paint and primers, and leaving the toys with rough wet surfaces that bred bacteria. In response, in 1937 Page made the first plastic ‘Kiddicraft “Sensible” Toys’, which could be brightly coloured without the use of paints, and which had the bonus of being able to be washed without incurring damage. Page explained their health benefits:

‘Mothers are becoming much more hygienically minded and they realise that every baby’s toy should be thoroughly washed in hot soapy water once a day. This can be done with toys moulded from urea. Dust and germs cannot cling to the bright shiny surface, and the range of bright colours is most attractive and interesting to the child.’

Many of Page’s plastic toys, such as the Building Beakers, Pyramid Rings, or Billie and his Seven Barrels, were based on wooden Russian toys he had previously imported. But there were also new designs, such as the Interlocking Building Cube, which would be awarded a British patent in 1940.

Toy production shut-down during World War Two, but when it reopened there was a rush towards plastics. With his head start in this field and the benefits of his study, Page was able to capitalise, and business boomed. He refined his interlocking cube design to create self-locking building blocks. These could be used to produce ‘sky-scraper’ models of almost six feet, as they were at the Earl’s Court Toy Fair in 1947. These interlocking cubes were seen by Ole Kirk Christiansen, who took the idea home to Denmark and in 1949 produced his now famous automated binding brick, later renamed LEGO.

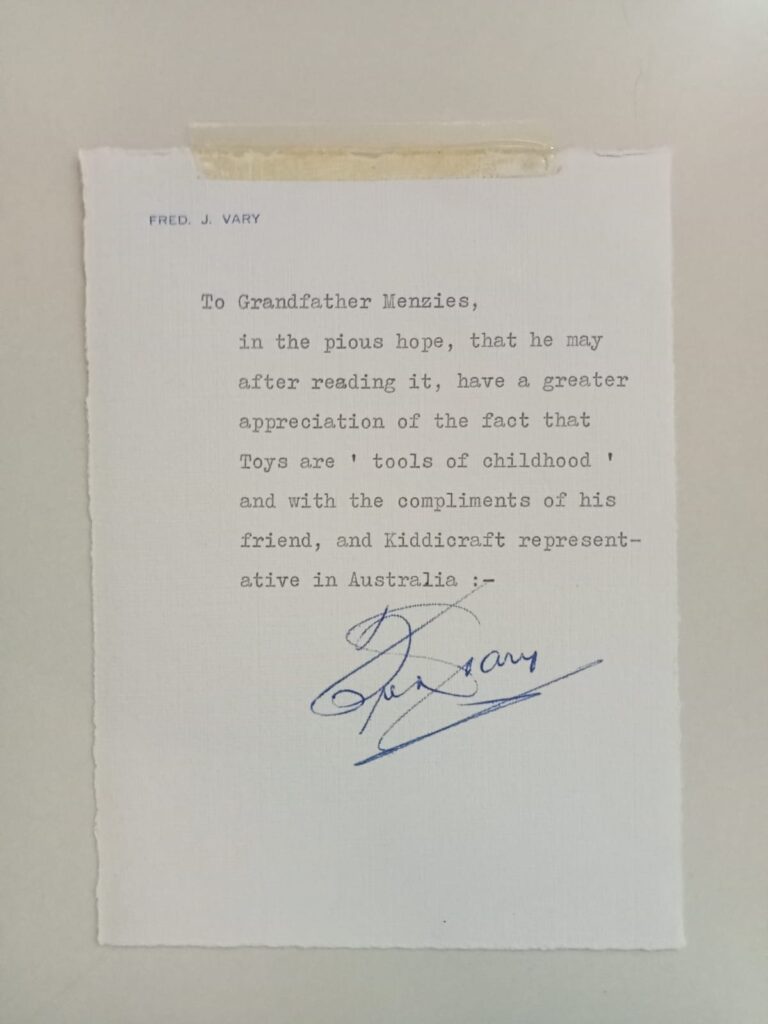

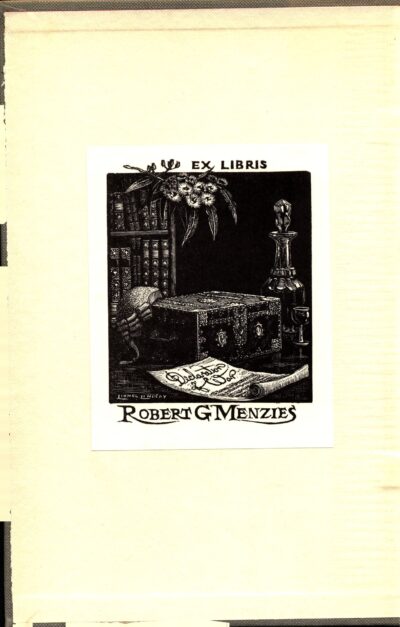

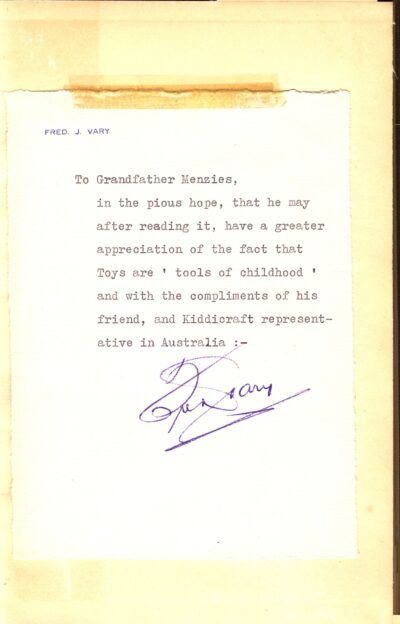

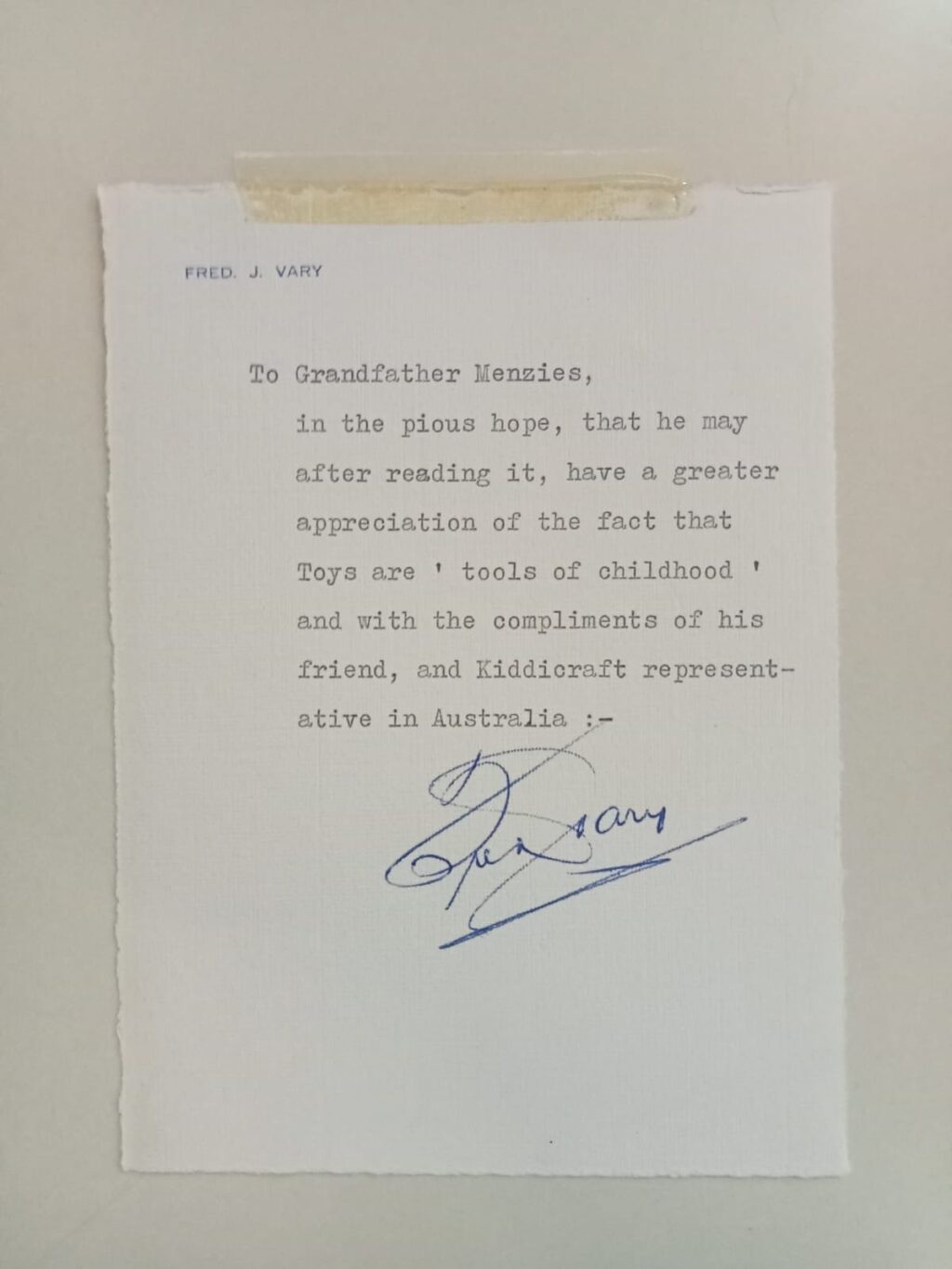

Menzies’s copy of Playtime in the First Five Years was a second edition of the book which even 15 years after its initial publication remained revolutionary. It was given to him by Kiddicraft’s Australian representative Fred Vary, and addressed to:

‘Grandfather Menzies, in the pious hope, that he may after reading it, have a greater appreciation of the fact that Toys [sic] are “tools of childhood”’

The book is a remarkable artefact of just how eclectic were the gifts which Menzies was given as Prime Minister, and how eclectic were the business interests that tried to influence him. With the benefit of being a British company, Kiddicraft was then one of the leading toy-makers importing to Australia, and while Page’s bricks never took off in the way their imitator did, many an Australian childhood was shaped by toys produced with the benefit of the insights of Playtime in the First Five Years.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.