John Reynolds, Edmund Barton (1948)

John Reynolds was a distinguished Tasmanian metallurgist with a penchant for journalism and historical research. He is now best remembered as the author of the first full-length biography of Australia’s first Prime Minister Edmund Barton. The book, which won a Commonwealth Literary Award and is still valued as a historical document to this day, was written partly at the urging of Reynolds’s friend Robert Menzies, who provided its foreword.

Born in 1899, Reynolds was educated at Friends’ School, Hobart, before studying chemistry at Hobart Technical School. He would go on to play a leading role in the establishment of the Australian aluminium industry, as well as selling wolfram and tungsten to the British Government. At the beginning of World War Two Reynolds was seconded to the Public Service to advise on the production of industrial charcoal for carbide manufacture. He held a number of advisory and official posts in Tasmania during the next two decades, including responsibility for the implementation of the Grain Reserve Act 1950.

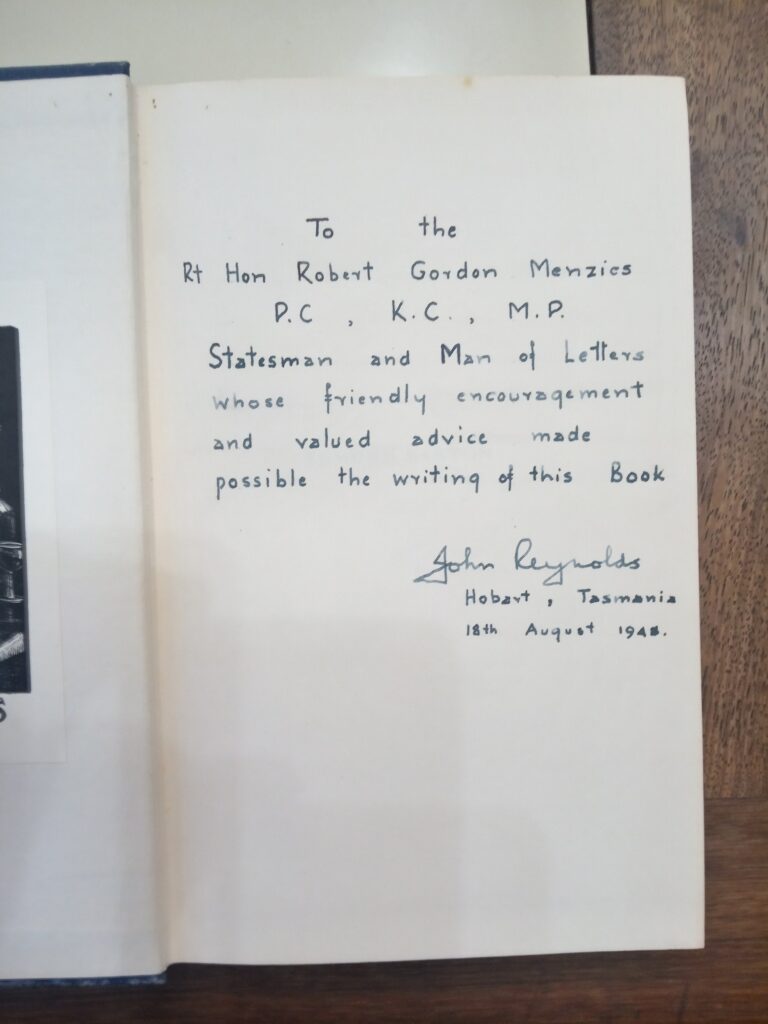

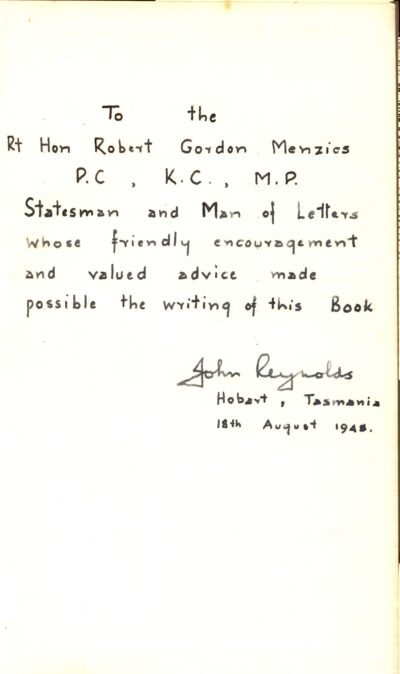

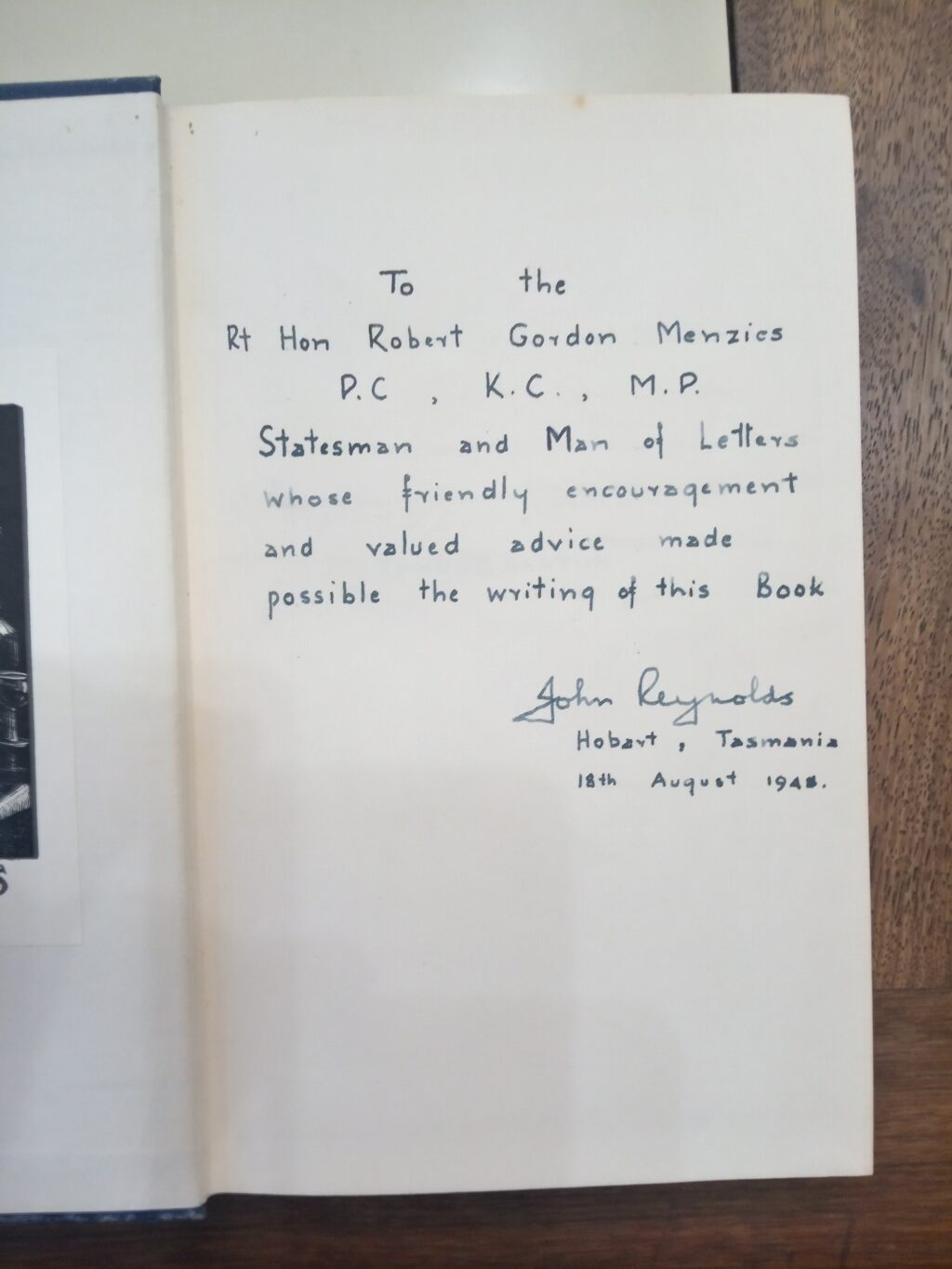

Reynolds had never authored a book before writing Edmund Barton, and his inscription in Menzies’s copy suggests that Menzies had encouraged him to make the shift from history enthusiast to active historian. It reads ‘To the / Rt Hon Robert Gordon Menzies P.C., K.C. M.P., Statesman and Man of Letters whose friendly encouragement and valued advice made possible the writing of this Book’. The book is thus evidence that Menzies was personally cultivating the study of Australian history, even before his record second stint as Prime Minister assured him of a central role in its story.

Menzies for his part was quite enamoured with Barton, whom he respected for his patriotism and involvement in the federation campaign, and who he had seen as a Justice on the High Court when Menzies was still a young barrister:

‘In all the accompaniments of justice he was magnificently equipped. A rich and beautifully modulated voice, a handsome and dignified appearance, exquisite courtesy, embracing both deference to his colleagues and genuine consideration for counsel, a clear sense of relevancy, a scholarly diction; all these things Barton possessed and practised. Taken singly, they are not commonplace; in combination, they marked Barton out for distinction.’

Despite these positive qualities, Barton had a bit of a reputation for being lazy, having what Menzies called ‘a just affection for leisure, for good company, for the warm pleasures of life’. A talented student, Barton entered the NSW Legislative Assembly in 1879 as the special member for the University of Sydney and would go on to become Speaker at the record-breaking age of 33. The University seat had a limited electorate, and after its abolition Barton would have a patchy record of winning a seat in general elections, twice shifting to the nominee Legislative Council where he did not have to face the electors at all.

This gave him the opportunity to devote much of his time to the fight for his dream of ‘a nation for a continent and a continent for a nation’, becoming the figurehead of the federationist cause after Henry Parkes’s passing, and topping the poll of NSW candidates for the Federal Conventions in 1897. While the accomplishment of his goal was undoubtedly a triumph, even in Federal Parliament Barton would only stand for one election unopposed for the seat of Hunter before moving on to the High Court, where he developed a habit of concurring with his fellow Justices’s judgements rather than going to the effort of writing his own.

Menzies’s foreword to the book is highly valuable as a document in its own right, as it reveals Menzies’s thoughts on the difficulty of assessing public figures, the art of biography, and the limitations of historical memory. These issues are inherently important topics when it comes to our longest serving Prime Minister, whose place in Australian history is arguably as hotly contested as any other single figure:

‘It is the fashion, and no doubt always was, to over-praise or over-blame statesmen while they are alive, and to forget them or forgive them when they are dead. Biographies of living men are usually extravagant and largely worthless. They are written, as a rule, by ardent admirers, and rarely possess any critical quality. They are, in short, propaganda documents to be discounted by the objective student.

In spite of my disillusioned beliefs on this matter, the extravagances of contemporary writing, both gay and grave, never cease to astonish me. A new cricketer arises; he is before long “the greatest player in the history of the game” according to some writer whose memory embraces less than a small fraction of one per cent. of those good cricketers who have lived and played. “The greatest speaker”, “the greatest debater”, “the most brilliant mind”, the “greatest scoundrel”; such phrases come trippingly from the mouths or pens of current recorders. Fortunately, these flashy judgements do not live. All too frequently, in the reaction which follows the death of some noted man, his memory appears to wither and the contemptuous indifference with which his name is recalled becomes absurd, and in its own way as extravagant, as the superlatives which attached to him when living.

And then, in due course, there comes along the detached historian to read about him, to study him in the round, to see his lights and shades, to assess his work and influence, to tear away the distortions of propaganda and reveal the true man.

Such a task must be fascinating, but almost incredibly difficult. What material is of value? Nowadays most of us don’t write letters except of a commercial kind, and the art of conversation is decaying. What contemporary records, then, are we to search? How can we get at the real inwardness of the statesman? By reading his speeches? I have heard hundreds of speeches in Parliament laboriously read by Ministers of the Crown, of which in most cases not one word was their own. By reading the contemporary press? Heaven forbid since partisan writers always aim to create a popular picture, and so produce in the receptive mind a series of legends which are basically false. The contest in politics always seems – to the partisan – to be one between the All Whites and the All Blacks but in truth it never is. At the best, the greatest statesman is a Grey Eminence.

The muse of history is an uncertain wench. Witness the famous passage from Sir Thomas Browne’s Urn Burial:

“But the iniquity of oblivion blindly scattereth her poppy, and deals with the memory of men without distinction to merit of perpetuity. Who can but pity the founder of the Pyramids? Herostratus lives that burnt the Temple of Diana, he is almost lost that built it; Time hath spared the Epitaph of Adrian’s horse, confounded that of himself. In vain we compute our felicities by the advantage of our good name, since bad have equal durations; and Thersites is like to live as Agamemnon. Who knows whether the best of men be known? Or whether there be not more remarkable persons forgot, than any that stand remembered in the known account of time? Without the favour of the everlasting register, the first man had been as unknown as the last, and Methuselah’s long life had been his only Chronicle.”

And so it is that the course and character of the work and personality of a public man must be studied closely and carefully delineated if the truth is to emerge.’

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.