The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley (n.d.)

Percy Bysshe Shelley was an English Romantic poet who had a short-lived but brilliant career before tragically drowning in a sailboat off the coast of Italy at the age of 29. The eldest son of a wealthy aristocratic family, by birth he stood in line to inherit not only his grandfather’s considerable estate but also a seat in Parliament, but this was not the path he would choose to follow. His parents sent him to the famed Eton College, where he resisted physical and mental bullying by indulging in imaginative escapism and literary pranks, before he went to Oxford where he was expelled for writing a tract entitled ‘The Necessity of Atheism’.

This was just the first expression of controversial political beliefs that included support for socialism, Catholic emancipation and ‘free love’. As the latter concept suggested, Shelley’s private life was no freer of controversy. He conducted open affairs, his first wife died by apparent suicide, and after this he offended propriety by remarrying in just three weeks. The new bride was Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, the author of Frankenstein, and Shelley was a significant figure in a bohemian sub-culture which thrived in Europe at this time.

Shelley’s works railed against the oppressive conditions that flowed from first the Napoleonic wars and then their aftermath. He advocated for greater equality, in economic and social terms, taking aim at the English aristocracy whose membership he had forfeited:

Men of England, wherefore plough

For the lords who lay ye low?

Wherefore weave with toil and care

The rich robes your tyrants wear?

Wherefore feed and clothe and save,

From the cradle to the grave,

Those ungrateful drones who would

Drain your sweat—nay, drink your blood?

Though the way he treated his spouses was far from perfect, Shelley’s concept of equality also embraced the emancipation of women:

Can man be free if woman be a slave?

Chain one who lives, and breathes this boundless air,

To the corruption of a closèd grave!

Can they, whose mates are beasts condemned to bear

Scorn heavier far than toil or anguish, dare

To trample their oppressors?

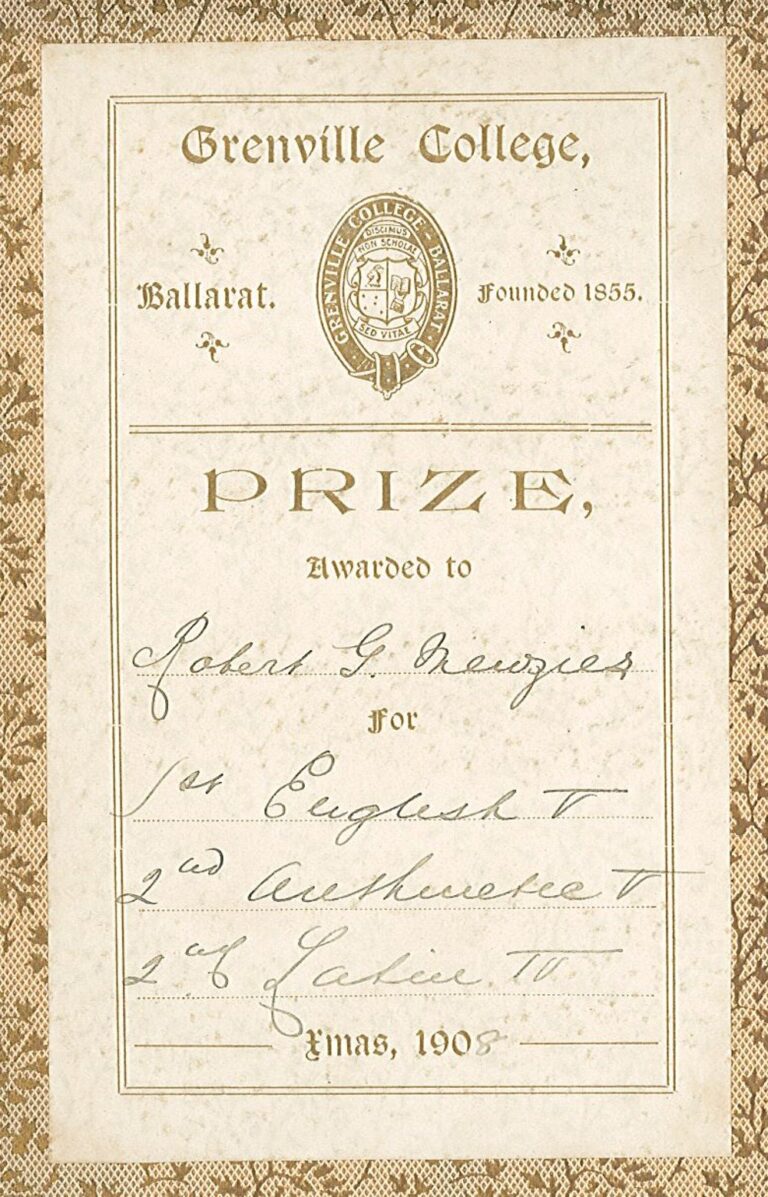

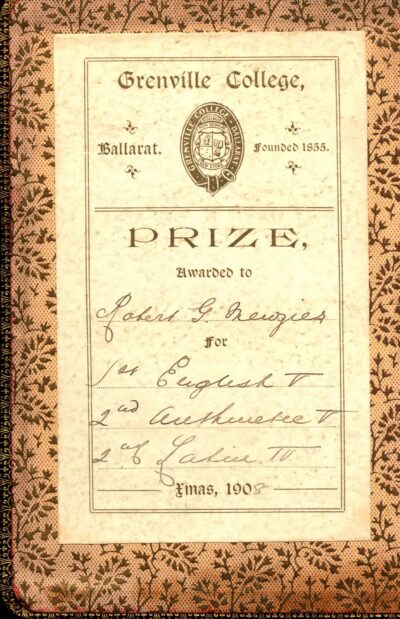

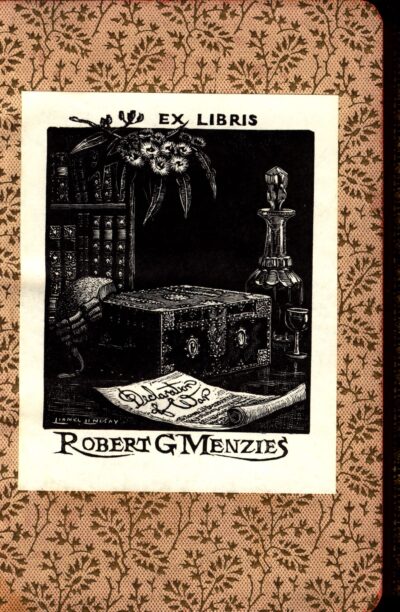

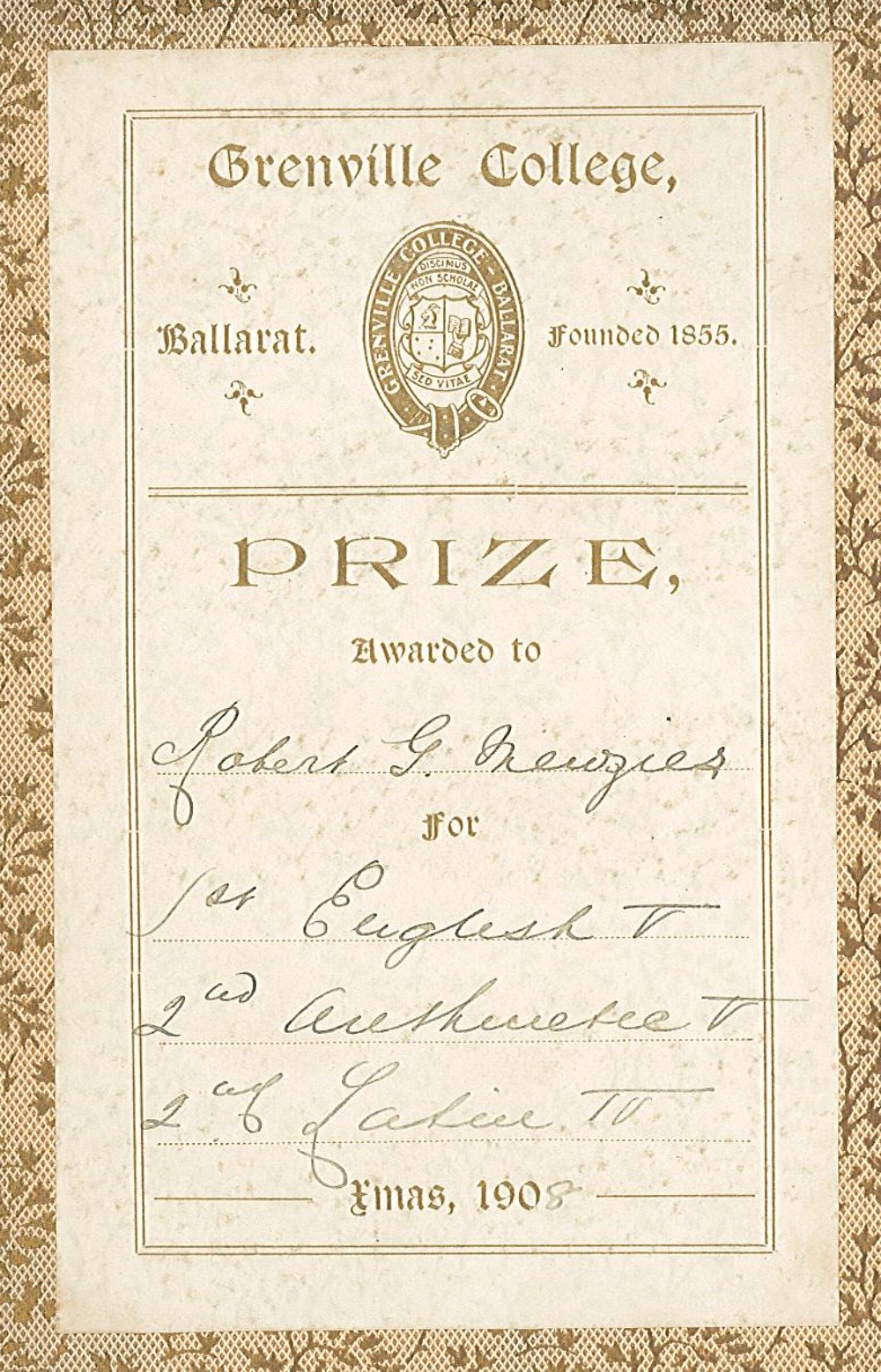

The Menzies Collection contains two copies of The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, and both have unique sentimental value. The first was awarded as a prize for English, Arithmetic, Latin at Grenville College Ballarat in 1908, when Menzies was just 14. The second was awarded to his later wife Pattie Leckie as a prize for boarders’ neatness at the Presbyterian Girls’ Grammar School in 1914, when she would have been 15.

The dual prizes are quite a striking coincidence, and they testify to the popularity of Shelley in Australia at the turn of the century, which is quite surprising considering his radical tone. Australia was certainly a liberal country with a great deal of egalitarianism, as demonstrated by both the early introduction of manhood suffrage and then votes for women – but Australia, and particularly these middle-class schools, were not places in which socialism and atheism could be expected to find favour.

The books are also evidence of the fact that Australian schoolchildren at the turn of the century were expected to read and to some degree memorise classical poetry, as an integral part of a rounded liberal education. Mark Rolfe has argued that this culture would go on to shape Menzies as an orator and politician:

‘Menzies was born in 1894 and was one of the last in a line of barrister-politicians since the nineteenth century who established their credibility as upright men with voters by quoting from the political and literary classics. High culture was a part of many politicians’ ethos, one of three means of proofs in rhetoric, which aims to garner the trust of an audience. No matter how rational, a speech will fall on deaf ears if an audience does not respect the credibility and character of the orator, who must employ the values of the audience and of the society in which they live’

Rolfe has suggested that Menzies’s oft-criticised line about the Queen ‘passing by’ was a manner of expressing one’s self which fit perfectly within this culture, but as ‘one of the last in a line’, by 1963 that culture had begun to die off resulting in a negative reaction based on misunderstanding.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.