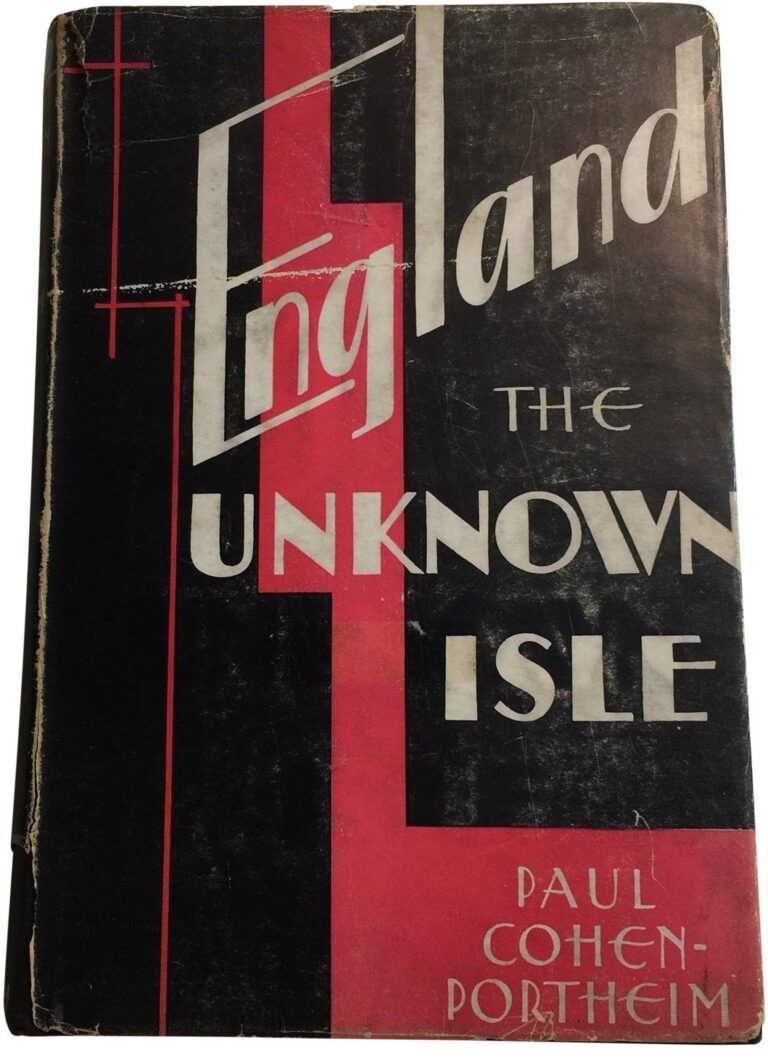

Paul Cohen-Portheim, England the Unknown Isle (1930)

Paul Cohen-Portheim was a European author, artist, and bohemian, who was described on his death as the ‘first citizen of Western Europe’ for his travel writing. Born in Berlin to a family of Austrian Jews, he happened to be in England at the outbreak of the First World War, and was consequently imprisoned as an ‘enemy alien’ for the duration. Curiously this experience, though harrowing, did not lead him to begrudge his captors, and Cohen-Portheim became something of an Anglophile, spending much of his life in London when not travelling.

England the Unknown Isle, which was published as an English translation of the author’s original text, provides a humorous, cutting, and satirical outsider’s view of England and her people. It describes England as a land of compromise, so much so that even the ‘English climate has the same antipathy to anything immoderate or extreme as its product the Englishman has; it is moody, but not preposterous or impossible — in fact, ambiguous.’ It was a place of strict etiquette, where liberty had thrived alongside conventionality, indeed ‘liberty is only possible within a framework of laws, and English liberty consists in imposing these laws on oneself’.

England was governed by unwritten rules, and these rules fed into a social hierarchy, in which ‘the upper classes make use of the rules of the game, the middle classes regard them with veneration, and the lower classes ignore them; but they stump the foreigner’. A class system was the product of an ‘individualistic’ culture convinced of the inequalities of people and races. A strong sense of aristocracy, part of the ‘Norman legacy’, provided strong leadership and a dose of character that other European countries had lost:

‘An-Oxford or Cambridge degree is regarded, and rightly, as stamping a man socially; a degree at one of the other universities as a certificate of expert knowledge in a certain department; a thing for which the Englishman has no more respect than he has for the expert knowledge of a tradesman or anybody else engaged in practical life. The valuing of personality above knowledge is a fundamental thing in the English character; an Englishman does not want to know what a candidate for a job has been taught, but what sort of a person he is— the opposite extreme from the usual German attitude.’

But while the author found much of this endearing, there were certainly harsh drawbacks to the levels of inequality prevalent in England. In the countryside ‘fear of the landlord is the beginning of wisdom’. Meanwhile, in the severe poverty of industrial towns the children were so malnourished that the vast majority of Royal Navy recruits had to be rejected on medical grounds.

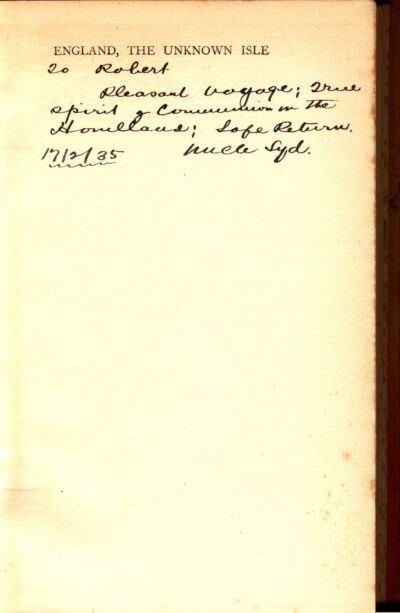

Menzies’s copy was a gift from his Uncle Sydney Sampson, given just as Menzies was travelling to England for the first time as a member of the Lyons Government’s ministerial delegation. It is signed ‘To Robert, Pleasant voyage; true spirit of Communion in the Homeland; Safe Return. Uncle Syd. 17/2/35.’ Sydney had been the Federal Member for Wimmera, and he was an important early influence and mentor of Menzies’s political career, giving harsh but honest feedback on his earliest speeches. One can expect there was a great deal of pride to be had in farewelling his nephew as he went to make a name for himself in the heart of the Empire.

Menzies’s biographer A.W. Martin describes this trip as one of the pivotal moments in Menzies’s life; a great voyage of discovery in which Menzies came face to face with an England he had been preconditioned by his upbringing to admire, and which he consequently fell in love with. Perhaps the outsider’s view of Unknown Isle was meant to educate Menzies on the cultural differences he would encounter, or perhaps it was meant to enlighten him on some of the pretensions of the aristocrats Menzies would soon be dealing with. Whatever the intent, the book serves as an evocative artefact of the relationship, the trip, and Australian attitudes towards the ‘mother country’. It is for these reasons that Sydney’s inscription in the book will be showcased in the upcoming RMI exhibition, housed in our museum in the Old Quad, to be launched in March.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.