W.Y. Tsao, Two Pacific Democracies: China and Australia (1941)

Wen Yen Tsao was the Vice-Consul for China, representing the Nationalist Government in Melbourne and later Perth during the Second World War. Born in Hangchow, he graduated from the National Central University with a Bachelor of Laws, before completing the Higher Civil Service examination for diplomatic and consular services in 1933. He came to Australia in 1936 to serve under Consul-General Pao Chun-Jien, a man well connected with the Kuomintang.

Two Pacific Democracies is a book defined by its context. Japan had invaded China in July of 1937, beginning a conflict that would wage until the end of the Second World War, and then give way to the Chinese Civil War. Japanese aggression and the Tripartite Pact meant that her entry on the Axis side of WW2 loomed as inevitable, but for the moment she was not part of the global conflict and essentially China was left to defend herself without help. These were the circumstances in which Menzies spent months in Britain as a member of Churchill’s War Cabinet trying to negotiate to bring more of the Allies’ resources to the East to protect Australia. Menzies appointed the first Australian Minister (Ambassador) to China, Frederic Eggleston, in May of 1941.

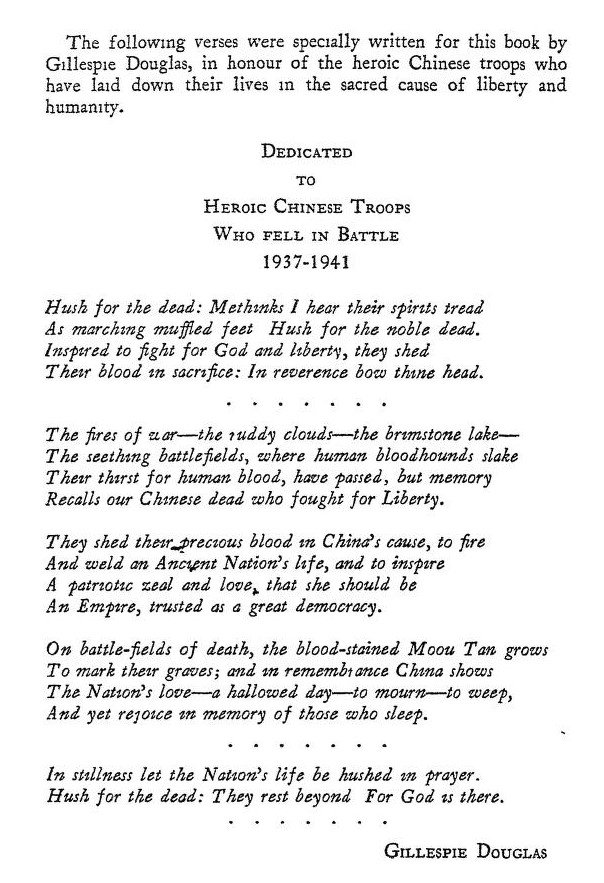

In this tense situation, Tsao sought to argue for the similarities between China and Australia, insisting that they both had an important role to play in ensuring the peace and wellbeing of the Asia-Pacific region, and appealing for support in China’s conflict with Japan. This was a difficult task considering the ingrained racial prejudices that Australians had long displayed towards Asian peoples, the same prejudices that had produced the White Australia Policy and which had only been exacerbated by fears of the approaching war with Japan. However, Japan would soon be a common enemy for Australia and China, and Tsao set out to demonstrate that not only was China Australia’s first line of defence, coming before even Singapore, but that both countries were fighting for the same thing in their respective wars, namely democracy and freedom.

He explained for example, that the Chinese Nationalist flag featuring a white sun in a blue sky shining over the red earth, symbolised liberty, equality, and fraternity, the creed of the French Revolution. The Nationalist Government followed the three principles of San Mi Chu I, which Tsao translated to mean nationalism, popular sovereignty/democracy, and the people’s livelihood (which others have translated to mean socialism, but which Tsao preferred to elaborate in the American phrase of ‘government of the people, by the people, for the people’).

Rejecting theories of racial hierarchy, the book insisted that ‘regardless of the pigment of the skin, the blood which flows in the veins of the entire human race is of a crimson hue’. Australia needed a united and independent China to keep the ambitions of Japan in check and ensure peace in the region. The age of imperialism and economic nationalism had wrought untold horrors, the solution was cooperation within a framework that recognised the sovereignty of each individual nation. Presciently, Tsao sold a free and developed China as a huge market for goods in a new world order that would be tied together by economic interdependence. If Australia would open itself up to closer ties with China, she would find that it was not a threat but rather an opportunity.

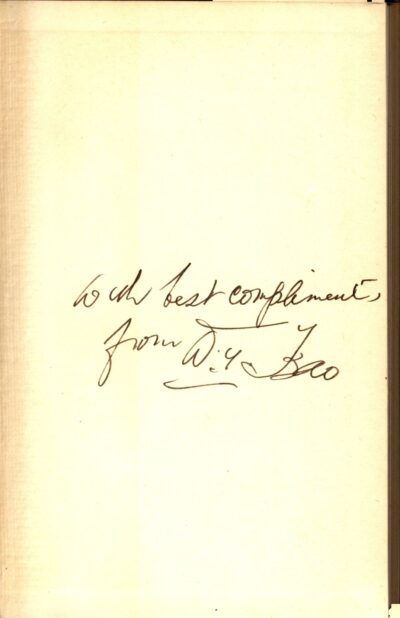

Menzies’s copy of Two Pacific Democracies has a personal inscription from the author, and was in all likelihood given to him in the months before he resigned as Prime Minister on 29 August 1941. It provides a stark illumination of the dire circumstances in which he had to operate. Japan had already shown herself to be an aggressor in China and a wider conflict in Asia seemed inevitable, but as much as Menzies may have wanted to offer Australia’s assistance, until war actually broke out it was extremely difficult to get the Allies to divert forces from the perilous situation in Europe. It was a circumstance in which Menzies was largely helpless.

However, after the war, when Menzies returned to power, he would follow part of the book’s thesis of economic cooperation preventing conflict by, ironically, offering Japan the olive branch of the 1957 trade agreement. That Australia did not develop closer ties to ‘China’ during the Menzies era was due to the fact that the government Tsao represented lost the Civil War and was confined to Formosa (Taiwan). For his entire time in office Menzies would continue to insist that this government was the legitimate government of all of China, a position that aligned with American policy, the UN Security Council, and above all the sentiments of a man who did genuinely wish that China had ended up being a Pacific Democracy.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.