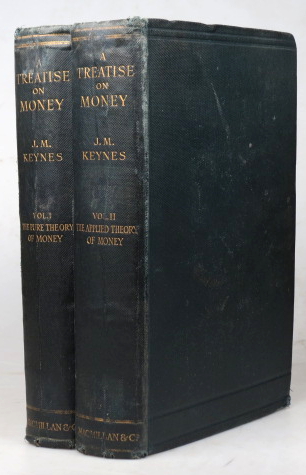

John Maynard Keynes, A Treatise on Money (1930)

The Menzies era was arguably the heyday of a Keynesian approach to Australia’s economic management, which sought to smooth out economic booms and busts by manipulating demand. The most famous aspect of this approach is its encouragement for governments to spend in times of financial difficulty to artificially boost demand, as exemplified by the Rudd Government’s cash handouts during the so-called Great Financial Crisis of 2008. But less well remembered, and certainly less frequently applied, is Keynes’s corresponding urging that during times of excessive growth, governments should deliberately cull demand by delivering budget surpluses to help bring down inflation. Something which carries with it far more political risk.

In modern Australia, the fight against inflation relies almost exclusively on the Reserve Bank raising interest rates, in a manner that passes the responsibility for any negative on to the Bank’s independent board. It also disproportionately hurts mortgage holders, and may even prove counterproductive by increasing the spending capabilities of those with large savings and investment. Keynes’s Treatise on Money was one of the earliest intellectual justifications for this use of interest rates, because it argues that where savings exceed investment, recessions would occur. Hence the best way out of a recession was to punish savings and encourage investment, via deliberate inflation. But when in good times inflation itself became the enemy, it was important to reverse course, and encourage people to save via higher interest rates.

The 1970s would show that there are several flaws to Keynes’s thesis, particularly during a period of ‘stagflation’, in which inflation occurs despite minimal levels of economic growth (Keynes had generally viewed these scenarios as inherent opposites). And even when the Treatise on Money first came out, it was subject to a savage critique by F.A. Hayek, whose writings subsequently became very important to the economic liberalisation of the 1980s.

But whatever the flaws of Keynes’s arguments, which would be developed more fully in his General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, during the Menzies period of extended prosperity the approach he advocated appeared to be working. Primarily because Menzies did not pick and choose those aspects of it that would be electorally popular, and was instead willing to bear the electoral consequences of a deliberately deflationary budget.

Most notably, in the case of the infamous ‘Horror Budget’ of 1951, delivered by Treasurer Arthur Fadden, in response to an inflationary crisis prompted by the Korean War wool boom. Fadden was very honest with the voters in explaining why temporary tax hikes and other hardships were needed, and appealed to their shared sense of ‘sacrifice’ for the greater national good. And while there certainly was electoral fallout from the decision, this mature approach earned considerable respect. Being lauded as principle and politically ‘brave’ by the newly established Australian Financial Review.

The great irony is that governments shying away from necessary but difficult decisions, which has been a characteristic of much of 21st century Australian politics, has not led to any greater electoral security on the part of our prime ministers. So perhaps earning respect through dishing out tough medicine, produced longer term political dividends, and it certainly paid economic dividends in underpinning Australia’s prosperity and a consistent rise living standards.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.