Gerald O’Collins, Patrick McMahon Glynn: A Founder of Australian Federation (1965)

When the Australian Commonwealth came into being in January 1901, Robert Menzies was just six years old. Yet because of his youthful and rapid rise to national prominence, Menzies would get the opportunity to meet and befriend several of our constitutional founders.

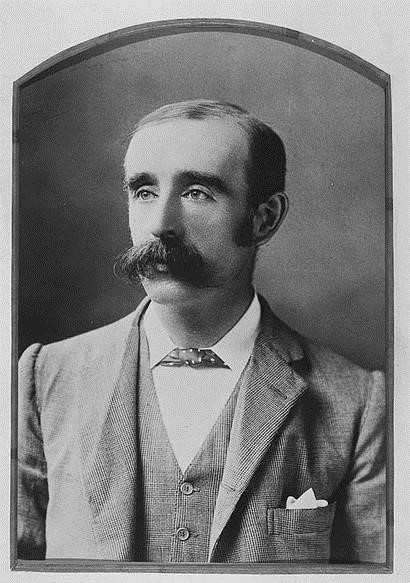

Perhaps his most surprising relationship was with Irishman turned South Australian lawyer and politician ‘Paddy’ Glynn, whom Menzies would describe as ‘talking like a silvertongued angel and looking like a black beetle’. Born in Galway as the third of eleven children, Glynn had had the privilege of attending Trinity College, Dublin. But his failure to translate his degree into a successful legal practice led to him migrating to Melbourne in 1880 in the hope of finding more fruitful pastures. Even there he could not gain consistent employment, but luckily he had an aunt who had helped to found the Sisters of St Joseph with Australia’s only recognised saint, Mary Mackillop. And that aunt was able to use her connections to secure him a job, opening a branch of an Adelaide law firm in the township of Kapunga.

From there, Glynn not only built up a successful legal business, but he also bought a newspaper and became involved in politics. He became President of the Irish National League of South Australia, and a devoted follower of Henry George, whose utopian ‘single tax’ theory led to Glynn becoming an ardent Free Trader.

Elected to South Australian Parliament as the member for Light, and later to the Federal Conventions of 1897-8, his most notable contributions to the Australian Constitution were to lead the judiciary committee and ensure that there was an acknowledgement of Almighty God inserted into the preamble. While this proposal was initially shot down, even in an era of strong sectarian feeling, the Catholic Glynn was able to attract enough support from Australia’s Protestant majority to lead to a popular campaign that succeeded in getting the motion over the line. Albeit with the introduction of a saving clause, making explicit that the preamble should not be used to institute a state religion (a notable warning for any modern constitutional amender, who thinks that preambles are merely words that can be used to virtue signal without legal consequence).

Elected as a member of George Reid’s Free Trade Party in 1901, Glynn would go on to serve as attorney-general in Deakin’s Fusion government (1909-10), minister for external affairs in the Cook (Liberal) administration (1913-14), and minister for home and territories in Billy Hughes’s Nationalist government from 1917. A devoted follower of his countryman Edmund Burke, Glynn was a small government Liberal who had outspoken views on the Murray waters question, Irish Home Rule, and even the need to introduce decimal currency (which Menzies would finally bring to fruition).

But despite this decorated career, Glynn lost his seat unexpectantly at the 1919 election, and found himself back in the law courts. Which is where he met and even began working with a young Robert Menzies, who had only recently graduated from the University of Melbourne. The Argus records that in October 1920 they both appeared for the appellant before the full bench of the High Court in a dispute over whether company profits consolidated into a general reserve fund, should be considered taxable income.

Glynn’s biographer and grandson Gerald O’Collins would himself become a very prominent Australian, as a Jesuit priest and academic. Though unfortunately, when he reached out to Menzies to write a foreword for his book, he caught the prime minister at a particularly busy time, and the request had to be declined.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.