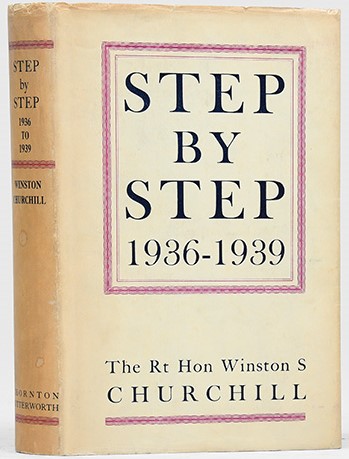

Winston Churchill, Step by Step: 1936-39 (1948)

Should countries which are engaged in a major war still conduct regular elections?

After all, getting the whole nation out to vote uses up a great deal of time, resources and energy, and elections can serve to divide the country along partisan lines in a manner that can impede its ability to join together in common purpose. Then there are the logistical problems of trying to collect the votes of servicemen overseas, or in the case of a country that has been bombed or invaded, civilian populations which have likewise been severely dislocated.

The decision ultimately hinges on two main factors: the extent of the existential crisis the nation is facing, as well as its cultural commitment to democracy, the latter of which may make it more willing to deal with the risks and divisiveness inherent in the exercise.

The United States for example, decided to conduct a presidential election in the midst of a devastating civil war in 1864, even though this effectively disenfranchised millions of citizens living in states which claimed the right to secession. But this was considered of vital importance, given that those states had seceded in response to the result of the 1860 presidential race, so the whole premise of the war centred on the binding nature of democracy.

In contrast, British history contains numerous precedents for having long periods between going to the polls – such as the aptly-named ‘long parliament’ which lasted for two full decades between 1640 and 1660. Hence the UK has tended to be far more willing to suspend elections during war time. Due to the First World War, no election was held in Britain between December 1910 and December 1918, and due to Second World War no election would be held from November 1935 until July 1945.

Step by Step is a collection of articles Winston Churchill wrote in the lead up to the latter conflict, which reveals just how out of place his repeated calls to stand up to Hitler were amidst the pro-appeasement consensus of those elected in 1935. Yet when Churchill was proven right, these same MPs turned to Churchill for leadership – thanks in no small part to the intervention of the Labour Party which refused to serve under any other Conservative leader. It was precisely because Churchill had not won a general election, that he was so devastated when he was unexpectantly beaten in 1945. And this was a major reason why he stayed on in politics, even as he grew quite old, so that he could finally be vindicated at the 1951 poll.

The Churchill example also reveals another factor which comes into play in a Westminster parliamentary system, which is whether the major parties are willing to come together to form a national government, and thus suspend the partisan political warfare which helps necessitate frequent elections in the first place.

In Australia, Labor’s resolute refusal to join a national government – even when Menzies offered that Curtin could lead it – has combined with a very strong cultural commitment to democracy and the luck of never having been directly invaded, to ensure that Australia has never suspended its elections due to a war. We held two in each of our great conflicts: 1914 & 1917, then 1940 & 1943, and even conducted two elaborate wartime plebiscites on the issue of conscription when we were under no constitutional requirement to do so.

Another difference between Britain and Australia, is that our written constitution does mandate that elections be held every three years, whereas Britain’s ‘unwritten’ and organic constitution is (and certainly was) far more flexible. It would take drastic intervention to lift the Australian constitutional requirement – but this was seriously considered when the Great War broke out in the middle of an election campaign in 1914. Labor and Opposition Leader Andrew Fisher, even criticised Liberal Prime Minister Joseph Cook for refusing a ‘political truce’, which might involve getting the British Parliament to pass legislation overriding the Australian constitution so as to reconvene a dissolved parliament. A move which would now be considered an unthinkable undermining of our national sovereignty.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.