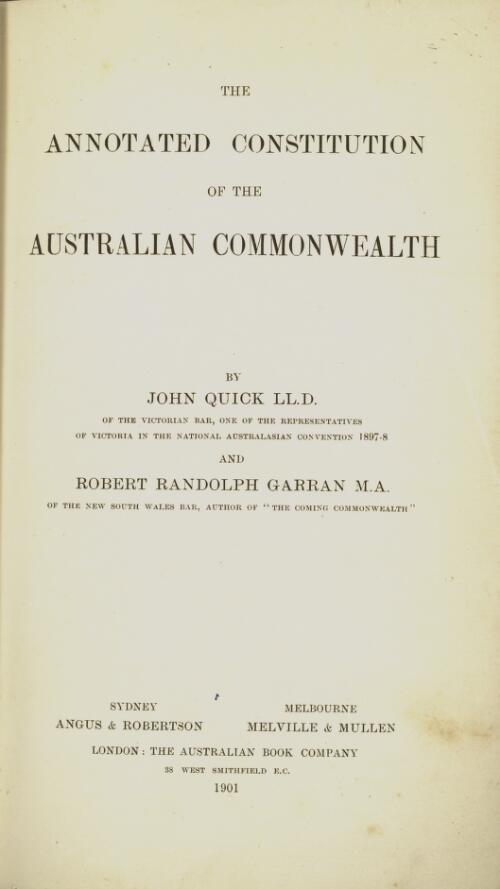

John Quick and Robert Garran, The Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth (1901)

Ever since its publication in 1901, the same year that the Commonwealth of Australia came into being, Quick and Garran’s Annotated Constitution has been the essential reference guide for those wishing to understand our nation’s founding document, and the logic used to justify each of its original clauses. Written by two insiders who played central roles in the story of federation, its authors knew the intimate details of the debates that had surrounded the long and complex process of bringing a unified nation into being. Although, as federal partisans, they inevitably took a pro-federation line on many of the more controversial aspects had animated the referendum debates of the late 1890s, through which the Australian people ultimately gave their consent to this new form of governance.

When we come across an aspect of the constitution which seems unusual, or at face value inexplicable, it is to Quick and Garran that we first turn to look for an explanation. Such as the ‘nexus clause’, which prevents the size of the House of Representatives from increasing to account for population growth, unless the Senate is also increased in a proportionate manner – a headache which Menzies tried to change via a constitutional referendum, which was ultimately voted down in 1967. Or Australia’s three-year election cycle, which has recently become the subject of much controversy for allegedly being too short.

To understand the Australian Commonwealth it is vital to understand that that it was ultimately the merger of six separate democratic polities, most of which had been successfully functioning under a responsible government model since the 1850s. Quick and Garran offer summary accounts of the constitutional history of each of the Australian colonies, and these reveal that there was a consistent impulse to reduce the length of parliamentary terms during this formative period of Australian democracy. In Victoria in 1859 the maximum period between elections was reduced from five years to three, a change which came to NSW in 1857, Queensland in 1890, Western Australia in 1899, and New Zealand (then considered a potential part of the Commonwealth) in 1879.

These reforms were all pushed by liberals, and they reflected the democratic view that the government should be held accountable by the people as frequently as practicable. Ultimately, the push can be traced back to the Chartist program which had gone so far as to demand that elections should be held yearly as the only sure-fire way by which the people could maintain their rights. Though the Chartists had been violently suppressed in Britain, many made their way to the Antipodes and succeeded in influencing the nascent political culture.

While in the 19th century and for much of the 20th century, Australians thought of themselves as being British, they equally prided themselves on being more democratic than Britain itself. Having rejected the creation of a landed aristocracy, granted both male and female suffrage earlier that the mother country, and instituted influential innovations like the secret ballot.

Our short terms are ultimately an expression of that same democratic sentiment, and indeed by the time of federation the argument in favour of short terms had been won so convincingly that there was little debate over the three-year election cycle. It was the undemocratic six years given to the Senate which was the controversy.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.