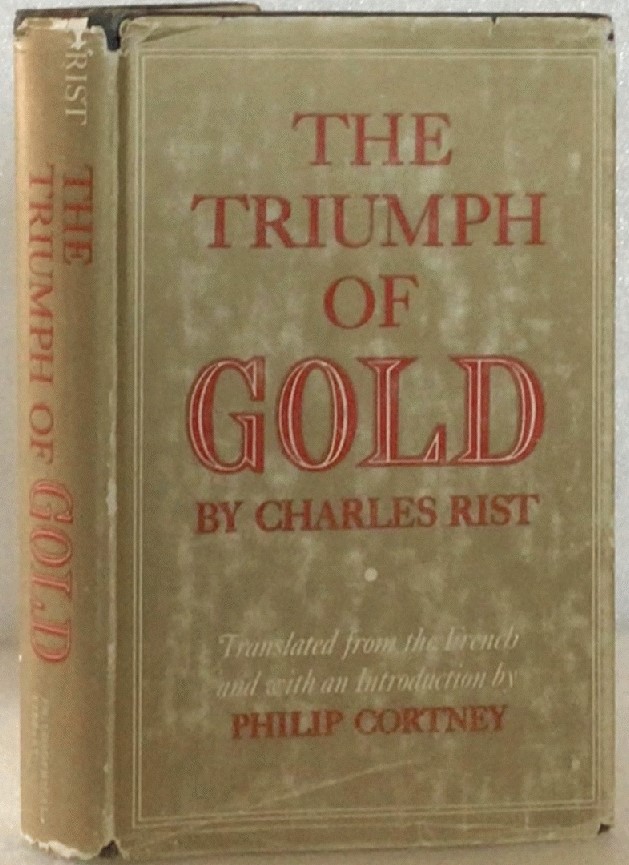

Charles Rist, The Triumph of Gold (1961)

Is the ‘gold standard’ a solution to inflation?

Robert Menzies was adamant throughout his career that inflation was one of the main economic evils that governments had to combat, because it represented an attack on something very dear to his heart: the Forgotten People (i.e. the middle class).

In a radio broadcast on the subject, he explained that:

‘[Inflation] was admirably described once in my presence as a “flat rate tax upon everybody’s pound note, whether the owner of the pound note is rich or poor.” So the first point to be observed about inflation is that it is inequitable taxation, since it is imposed upon everybody at the same rate.

The second thing to be noted about it is that, by reducing the value of money, it reduces the value of money claims such as savings, bank credits, insurance policies, investments on mortgage, preference shares and the like. Competent observers have contended that the German inflation after the last war practically wiped out the middle classes, and thereby paved the way for the rise of national socialism.

I have had occasion before to say something to you about the damaging effect of too many of our policies on those thrifty and frugal people who are the backbone of the nation. What I want to point out to you tonight is that these are of all people the ones who would be most grievously injured by inflation.’

And in a sentence that is perhaps revealing for modern issues, Menzies went on to suggest that ‘some big business men are indifferent to the danger of inflation. I think I understand some of their reasons, and I shall not take up your time tonight by discussing them, except to say that great wealth and selfishness are not always strangers to one another.’

Because Menzies felt that inflation was such a crucial issue, he was willing to risk his political career to combat it. Most notably via the ‘Horror Budget’ of 1951, a deliberate and quite harsh deflationary exercise that recalls a time when governments did not merely offload the issue to the Reserve Bank to tackle via interest rates alone.

Yet despite this, Menzies proved unwilling to take on what some argued was a root cause of inflation, namely that ‘a pound note is intrinsically worth only the paper and ink used in its manufacture’ because it was no longer backed by anything.

Prior to 1932, the Australian pound had been backed by very real and tangible gold reserves. However, when the Great Depression hit, many blamed this gold standard as one of the exacerbating factors making the crisis much worse than it needed to be.

Authored by French economist Charles Rist, The Triumph of Gold seeks to dispel this idea. It argues that one of the main causes of the Depression was that because of the unique circumstances of the First World War, American currency had only theoretically subscribed to the gold standard. Because the US had been printing vast quantities of notes based on gold that was only temporarily stored in America by European nations engaged in the conflict. Moreover the war had spawned over-production, meaning that prices were bound fall, resulting in postwar deflation which had been common throughout the centuries. This phenomenon had made what Rist dubbed ‘Anglo-Saxon economists’ lose sight of gold’s greatest strength:

‘The ability to conserve purchasing power… It is contrary to the most elementary justice and to the welfare of individuals that the amount of money received in exchange for services or merchandise should fluctuate rapidly over a period of time, causing the one who has received it to lose the benefits of the services or merchandise furnished by him.’

That Menzies never acted on the issue is in part explained by Rist himself, as the economist accepted that it was no longer possible for a nation state to return its currency to the gold standard in isolation from the rest of the world. So at best, Menzies could have used his prestige as a statesman to try to lobby for an international monetary revolution. Which plainly he was not willing to do, particularly as Menzies was on the record as saying that he was ‘no economist’.

Nevertheless, Menzies’s copy of The Triumph of Gold is still an interesting artefact by virtue of who sent it to him: the President and Councillors of the Chamber of Mines of Western Australia (Inc.), Kalgoorlie. Fresh off their triumph in convincing Menzies to end the iron ore export embargo (the lifting of which would usher in the first stages of Australia’s mining boom), these mining magnates were clearly keen to get Menzies to adopt a policy that would place a new impetus on gold exploration.

It was a bold ploy, but you can’t blame them for trying.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.