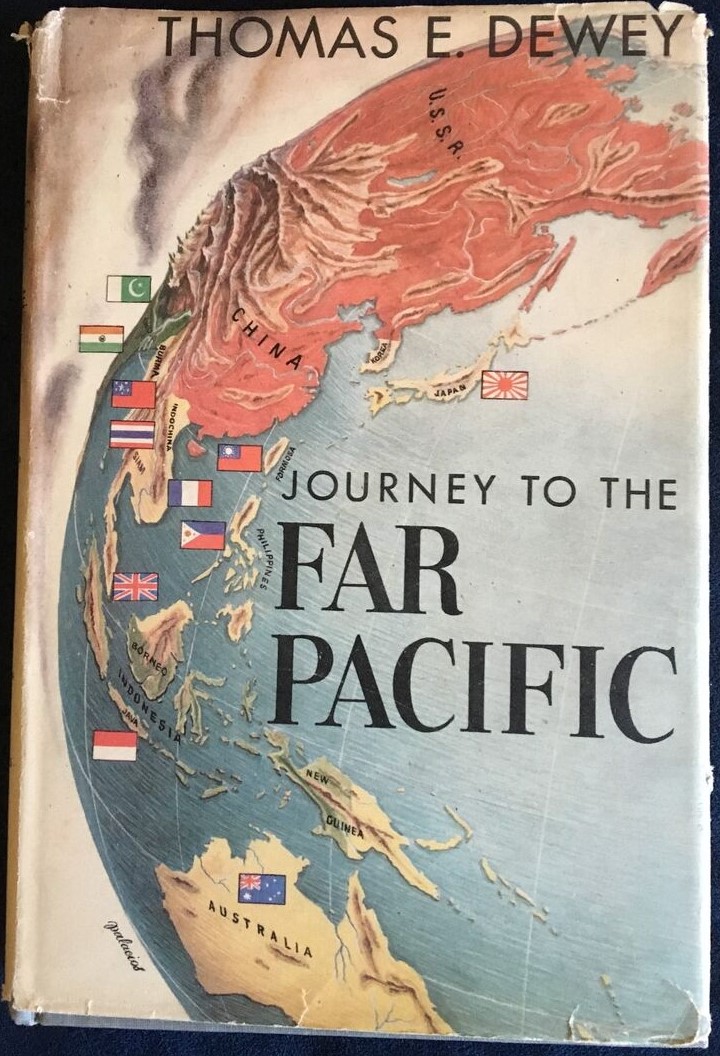

Thomas E. Dewey, Journey to the Far Pacific (1952)

Robert Menzies got to know all five American Presidents who served contemporaneously with his extended reign as Australia’s prime minister, and their various relationships have been well documented by historians. But what is otherwise lost to history is the friendships Menzies developed with men who were almost president. The most notable of which was with New York Governor turned Republican nominee Thomas Dewey.

Dewey was so heavily favoured in the polls for the 1948 presidential election, that newspapers infamously incorrectly printed editions claiming that he had won. Menzies as Opposition Leader was visiting the United States during this tumultuous period, and was even introduced at speaking engagements as ‘Australia’s Dewey’. He later recalled that:

‘All the polls were against [Truman]. The newspapers were busy foolishly explaining who would be in the Dewey administration and, in a nation which does not have compulsory voting, lulling Republican supporters into a false certainty of victory.’

Luckily for Australia, Menzies had not been so naïve as to predict a victor, and had met and struck a chord with both nominees. Nor did he cold shoulder the defeated candidate, for when he returned to America as PM in 1950, he stayed at Dewey’s dairy farm in Pawling, New York. There he so impressed Dewey’s two teenage sons, that they apparently dubbed him the ‘greatest man they had ever met’ – quite the compliment considering they also knew the likes of Winston Churchill.

Even Truman himself remained on good terms with Dewey, and the two became unlikely allies in a bitter debate over the United States stationing troops in Western Europe to forestall any potential Soviet invasion. There were fierce isolationists in both parties who had argued that such an act was not only expensive, but might in itself act as a provocation to the Russians.

The pro-NATO side won out, and subsequently Dewey was encouraged to embark on a fact-finding mission across the Pacific to raise awareness of its defensive needs in likewise resisting communist aggression. As part of the tour he visited Australia in August 1951, having lunch with Menzies, and publicly warning about communist ambitions to ‘acquire the industrial capacity of Germany and Japan’. For this reason he argued that Japan needed to be kept strong and pro-Western, via the ‘soft’ peace treaty that would be signed in San Francisco the following month. Dewey was acting as an advocate for the treaty, which was highly controversial in Australia. The Menzies Government supported it, but faced fierce opposition from the Labor Party and its allies. In contrast to this bitter partisan struggle, Dewey was essentially in Australia to sell the foreign policy of the man who had been his opponent.

The book Journey to the Far Pacific is an account of Dewey’s trip and the insights he gleamed from it. There are chapters covering a host of Asian nations, including Japan, Korea, Formosa, the Philippines, Hong Kong, Indo-China, Angkor, Malaya and Indonesia; and they reveal how many of these had their own concerns about the treaty that had to be delicately handled. Australia and New Zealand do not get similar treatment in the book, with Dewey giving the justification that:

‘Australia and New Zealand are the southern anchors of the Pacific defense line, and are to be protected by the pending treaty of mutual defense [ANZUS]. Alaska is the northern anchor. Since it is clear that we would immediately go to the defense of either area in the event of attack, I have omitted from this book chapters on my visits there. I do wish, however, to express my warm gratitude to the people of those British Pacific Dominions and of Hawaii and Alaska for their generous hospitality to me and to the members of my party.’

But the book still has a number of interesting perspectives on matters of great concern for Australia. Beyond the negotiations that went into the treaty, and domino theory warnings about the vulnerabilities of the countries in our region, by far the most striking is Dewey’s argument that it was a Dutch bluff that ultimately saved Australia from an invasion by the Japanese:

‘We have since learned that [the Japanese] intended to by-pass the Dutch East Indies and occupy Australia, which they expected to accomplish without difficulty. The Japanese heard, however, that the Dutch had large military forces on the island of Java which they did not dare leave behind them as a threat to their lines of supply. The Dutch did have large forces— but what the Japanese didn’t know was that they were mostly untrained civilians in uniform. When I met the director of the Bogor Botanical Gardens, a middle-aged man who had never carried a gun in his life, he told me how he, like every other Dutchman able to walk, had suddenly found himself in the army when the war broke out. The Dutch did it partly in the hope of creating the illusion of a large army to keep the Japanese away, and partly to give their civilians the status of military prisoners of war if the islands should be taken. Alarmed by the apparent size of the Dutch Army, the Japanese changed their plans and attacked Java first, with considerable resulting delay in the Japanese attack on Australia. The delay gave us and the Australians the precious time needed to build up the military and naval forces which saved Australia when the Japanese later attacked.’

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.