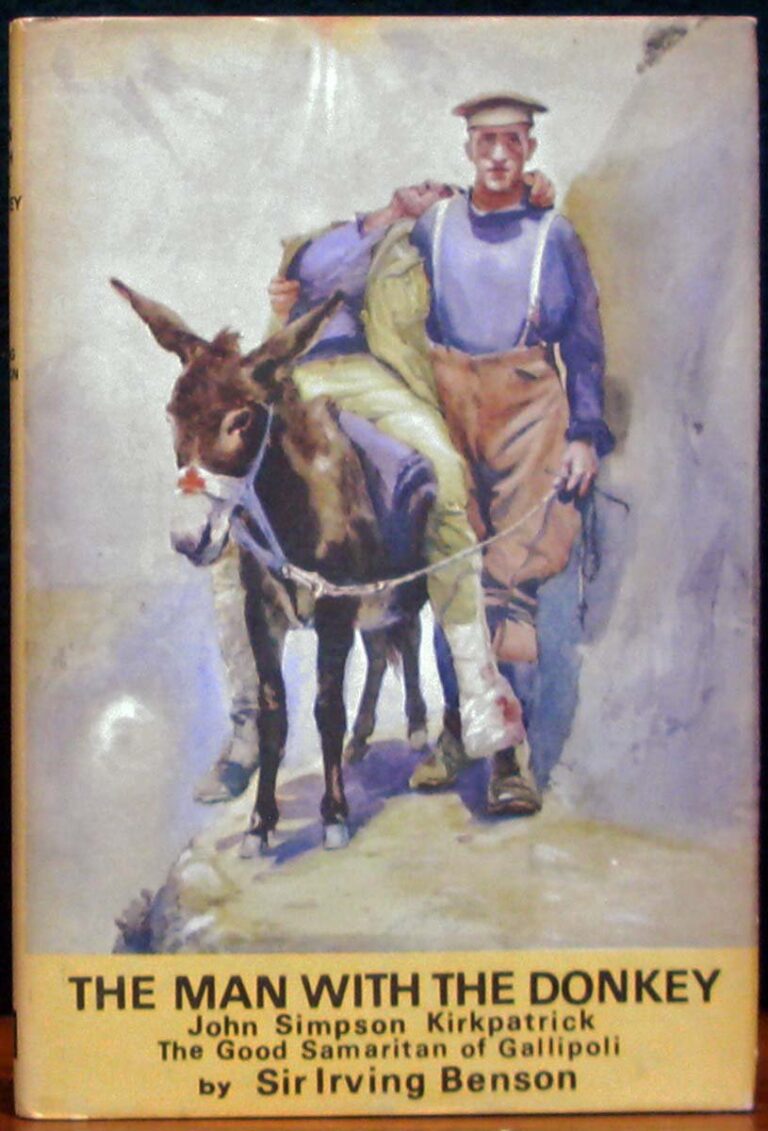

Sir Irving Benson, The Man With the Donkey: John Simpson Kirkpatrick, the Good Samaritan of Gallipoli (1965)

Sir Clarence Irving Benson was a prominent Methodist Minister, known for his weekly ‘Church and People’ column which ran for many decades in the Melbourne Herald. He was also the brainchild and organiser behind the ‘Pleasant Sunday Afternoon’ talks, which his ADB article describes as a ‘national institution’ avidly listened to on radio sets throughout the country.

A central thread of the talks was ‘spiritual renewal rather than… an interventionist state as the way forward in the postwar period’. This corresponded closely with Menzies’s own views as to the necessity of individual exertion to drive progress, and Menzies became a close friend of Benson, frequently delivering FSA talks which often formed some of his most iconic speeches. Benson was also an avid commemorator of Anzac Day, and became very enamoured with the iconic story of Simpson and his donkey.

Benson spent years researching to write a biography of Simpson, the details of whose life were little known up until this point. What was known is the immortal story of how for four straight weeks Simpson and his donkey carried wounded men from the front line down the awful slopes of Shrapnel Gully, constantly under fire, to the dressing station on the beach. Until a bullet from a Turkish gun finally took his life.

While Simpson was already an icon, The Man With the Donkey is credited with having taken the legend surrounding him to new heights. The book was released for the 50th anniversary of the Gallipoli landings, and corresponded with a number of Menzies Government initiatives to commemorate the occasion. These included producing a series of three special Simpson and his donkey stamps, as well as giving every surviving veteran of the Gallipoli campaign ‘a handsome medallion and lapel badge featuring Simpson and his donkey’.

Despite its heroic subject matter, Benson’s book has become the matter of some controversy. In 2011, in response to a long running campaign to posthumously award Simpson the Victoria Cross, the federal government launched an inquiry into the Simpson story. It closely examined Benson’s sources, which included the only firsthand testimony from a man with life threatening injuries who had been rescued by Simpson. However, it was found that the man’s service records did not match the account. This was one of several reasons why the inquiry ultimately concluded that there were not sufficient grounds on which to award Simpson the Victoria Cross.

But that certainly does not mean that Simpson was not a hero. He was commended in official dispatches for his work attending the wounded at Gallipoli, and there is no disputing that he ultimately gave his life for his country. What really seems to have happened is that Simpson is the man around whom the heroics of many different medicos have been woven. While obviously these other men of valour deserve to be recognised, there is something to be said for the narrative power of a single story, and of course the iconic donkey. Simpson embodies the greatest Australian characteristics, and therefore makes their digestion and veneration a simpler task. He is and will be remembered not so much for who he was, but for what he stands for.

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.