William Sharp McKechnie, The New Democracy and the Constitution (1912)

William Sharp McKechnie was lecturer in Constitutional Law and History at the University of Glasgow from 1894-1916, then a Professor of Conveyancing at the same institution from 1916-1927. During this time, he produced a number of valuable works of political theory and history, most notably a commentary on Magna Carta which was the first detailed examination that the famous charter had received since 1829.

The New Democracy was written in the aftermath of the Parliament Act of 1911, which had removed the House of Lord’s absolute veto over legislation, establishing the supremacy of the democratically elected House of Commons in the UK Parliament. Though the Representation of the People Act granting votes to all men over the age of 21 and women over the age of 30 would not come until 1918, McKechnie saw these reforms as inevitable now that the UK had abandoned the logic of the ‘mixed constitution’ in which the will of the people was ‘tempered by the survival of counterbalancing royal and hereditary influences’.

The UK was becoming a pure democracy, and the author wanted to examine what that would entail. McKechnie was particularly concerned that with an electorate made up of people who were frequently uneducated and even illiterate, politics might quickly degenerate into a tyranny of the majority, where self-interest rather than principle would rule.

The New Democracy attempts to identify the core characteristics of the triumphant democratic philosophy, highlight its potential flaws and negative consequences, and then, accepting that there was no turning back the forces of progress, propose solutions to those issues. Most of these boil down to introducing American-style checks and balances, and even a system of federalism, to ensure that majoritarianism does not result in the absolute domination of the minority. McKechnie also suggested giving a second chamber powers over taxation and creating a non-political council of financial experts to help to guide the new democracy away from destructive schemes, proposals which the book’s reviewers slammed for being politically unworkable.

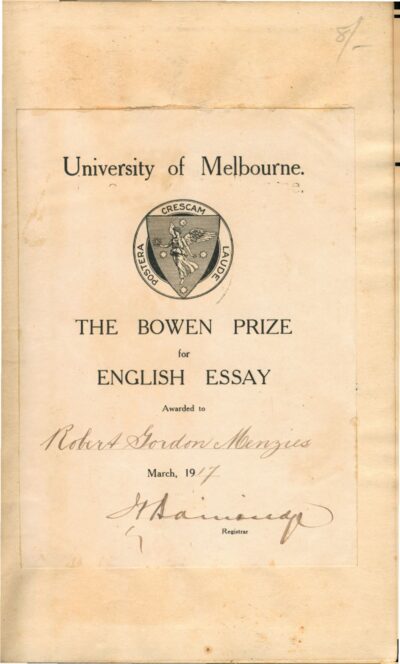

Menzies received his copy of The New Democracy as part of winning the Bowen Prize for English Essay at the University of Melbourne in 1917. The Australian Colonies had experienced their own parallel struggles for universal suffrage and the supremacy of the various Legislative Assemblies over the Legislative Councils, but with an egalitarian culture that was greatly influenced by the chartist movement, these issues had been resolved in Australia far earlier than in Britain. During the subsequent passage of time, Australian experience had proven that a more pure democratic system was workable, though certainly on issues like White Australia the populist and ignorant majoritarianism which McKechnie feared had revealed itself.

Menzies’s copy of The New Democracy shows signs of intensive use which indicate that he shared some of the author’s concerns. For example, on page 123 the sentence reading ‘The politician who advises the sovereign people to sacrifice their own present gratification for the benefit of posterity will have a short career’ is marked out. Likewise is the sentence ‘Candidates, who take their chances of election seriously, must do more than merely colour facts to please their audience; they must promise more tempting gifts than their opponents’ on the proceeding page.

The question is what to make of this. Do the markings indicate a certain Machiavellian understanding of the impulses of the electorate which Menzies believed could be exploited? Or do they represent genuine anxieties which initially dissuaded Menzies from pursuing politics before he eventually decided that it was his public duty to attempt to overcome them?

The latter certainly seems to have been borne out by his career, as Menzies sold himself on the persona of a long-term national builder and steady hand at the wheel, rather than a gift giver who would spend lavishly on short-term luxuries. During his 1955 policy speech Menzies declared:

‘We have never sought your votes by offering bribes, nor are we spruikers at old-time country shows offering gold watches for five shillings. We have sought and obtained solid progress. We have been sensible and honest.’

In 1961 he almost lost an election over the ‘credit squeeze’, policies which he felt were in the long-term interest of the country even if they were tremendously unpopular. With his strong emphasis on education, Menzies was determined to transform Australia’s democracy into one guided by political principle, which would overcome the issues identified but never satisfactorily resolved in The New Democracy.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.