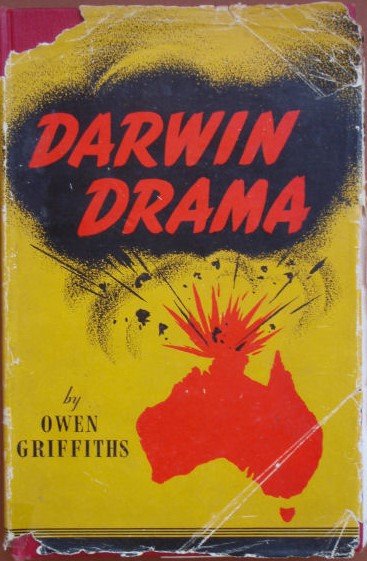

Lieutenant Owen Griffiths was a captain’s secretary and navy paymaster serving aboard the depot ship HMAS Platypus in Darwin during World War Two. He was onboard the ship when the Japanese launched their devastating bombing raid on 19 February 1942, and recalled the event with meticulous detail – despite authorities explicitly denying him the privilege of keeping a diary. Published in 1947, Darwin Drama was his firsthand account of all that he had experienced, which at a time when wartime censorship had greatly whitewashed the horror of the events, came as quite a shock to the Australian public.

The book begins simply enough with Griffiths explaining: ‘This is the story of Darwin. It is a simple story of some of the every-day things which I saw and experienced during my service in and around the romantic frontier post.’ The narrative’s emotional poignancy is given added weight by the way in which Griffiths builds up a picture of the joyous naivety of young men who were ill prepared for what was about to hit them:

‘They were roaring days… Wages were high and work was plentiful. Naval, Army, and Air Force personnel flooded the town, with full pay envelopes and nowhere to spend them. The hotels and gambling houses did a brisk business. A party of soldiers staged a riot in the town one night.’

Griffiths is likewise openly enamoured with Darwin as a scenic and pleasurable posting, which he describes as a cross between an American Western town, a tropical port of the East Indies, and an ordinary Australian bush town. Its beauty is stunning:

‘The Darwin moon was bright and clear. It softened harsh features of the countryside and cast a spell upon the land. Exotic frangipanni, bathing in the moon light, took on the colour of the moonbeams, and its soft, amorous scent brought dreams of mystic fairylands and enchanted places.’

But all this calm and tranquility was soon interrupted, as the Japanese came on with stunning rapidity and overwhelming force:

‘The air over the harbour was comfortably full of Japanese dive bombers and fighter planes. There seemed just sufficient room between each to allow the next one to manoeuvre. There were so many planes diving and twisting about that at first I thought the enemy planes were having dog-fights with our planes.’

Griffiths vividly recalled the American Destroyer Peary, which tried to escape port and make it into the open ocean:

‘I can see It now — they seemed to be concentrating on Peary — her decks were awash, but she still fought back. It was fascinating to watch. Her crew were in imminent danger of her magazines exploding, for she was now burning fiercely, but they fought on to the last… The ship appeared to disintegrate in a burst of flame, which seemed to grow out and reach a height of more than a hundred feet. She finally pointed her nose to the sky and disappeared in a pall of heavy, black, oily smoke, the gun on her fo’c’sle firing to the bitter end.’

Finally, the Griffiths surveys devastating aftermath:

‘The scene round about was tragic. The skyline over the town and beyond was thick with black smoke. Many fires were in evidence. Every visible merchant ship, troopship, and tanker, all big vessels, was sinking or burning or both.

Bodies, dead and alive, were floating in the harbour. All things floating, including bodies, were covered in thick oil. Nearby, the wharf and the two ships alongside were still burning fiercely. The Neptuna was heavily loaded with explosives. We became conscious of a low rumbling noise coming from her. “She’s going up!”, came a warning cry. Everyone lay flat as the Neptuna, and everything in her, blew sky high with a colossal explosion.’

The 5,962 tonne Neptuna was just one of several ships destroyed that fateful day on which 252 Allied personnel lost their lives. Subsequent raids would occur for over a year, but none of them would match the scale and intensity of the well over 200 enemy aircraft which began to appear over Darwin just before 10am on 19 February. It remains the largest single attack ever launched against Australia.

Later in the month when the news broke, Menzies would address the attack in one of his ‘Forgotten People’ radio broadcasts. Telling the nation solemnly:

‘Darwin has been bombed and Australian lives have in this war been lost on Australian soil. The war has come home’.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.