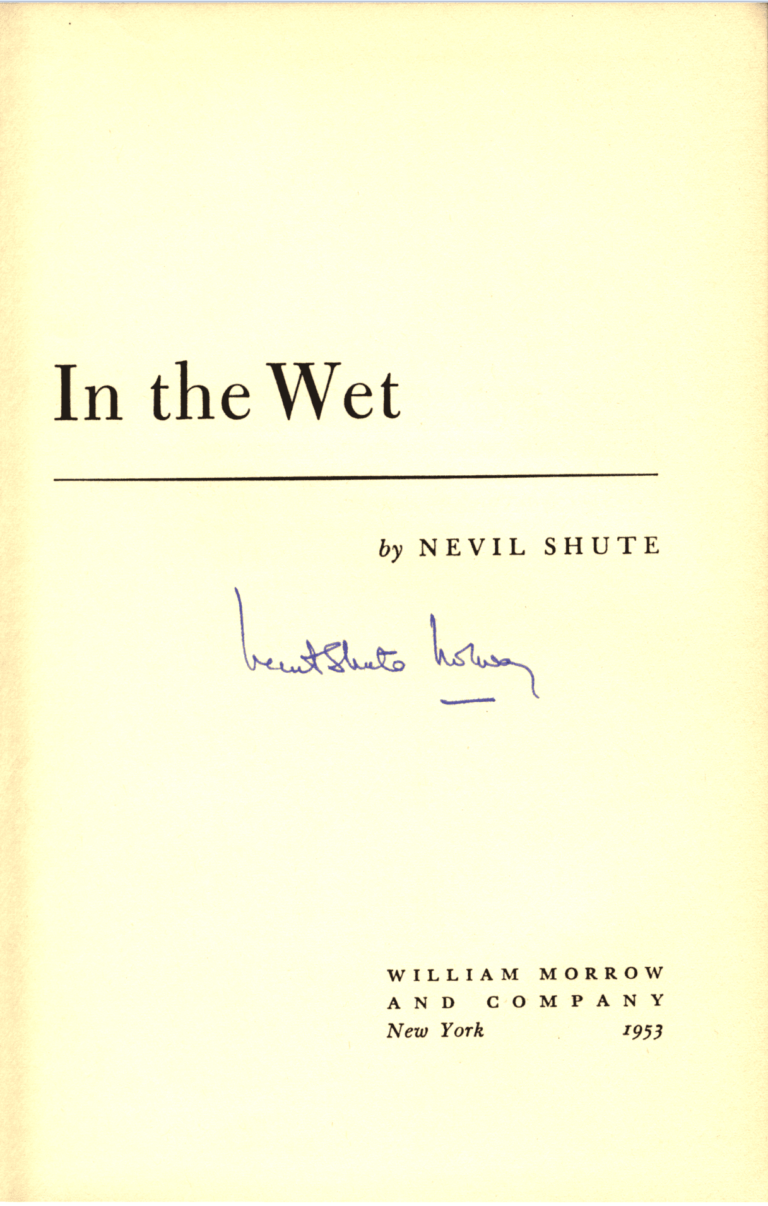

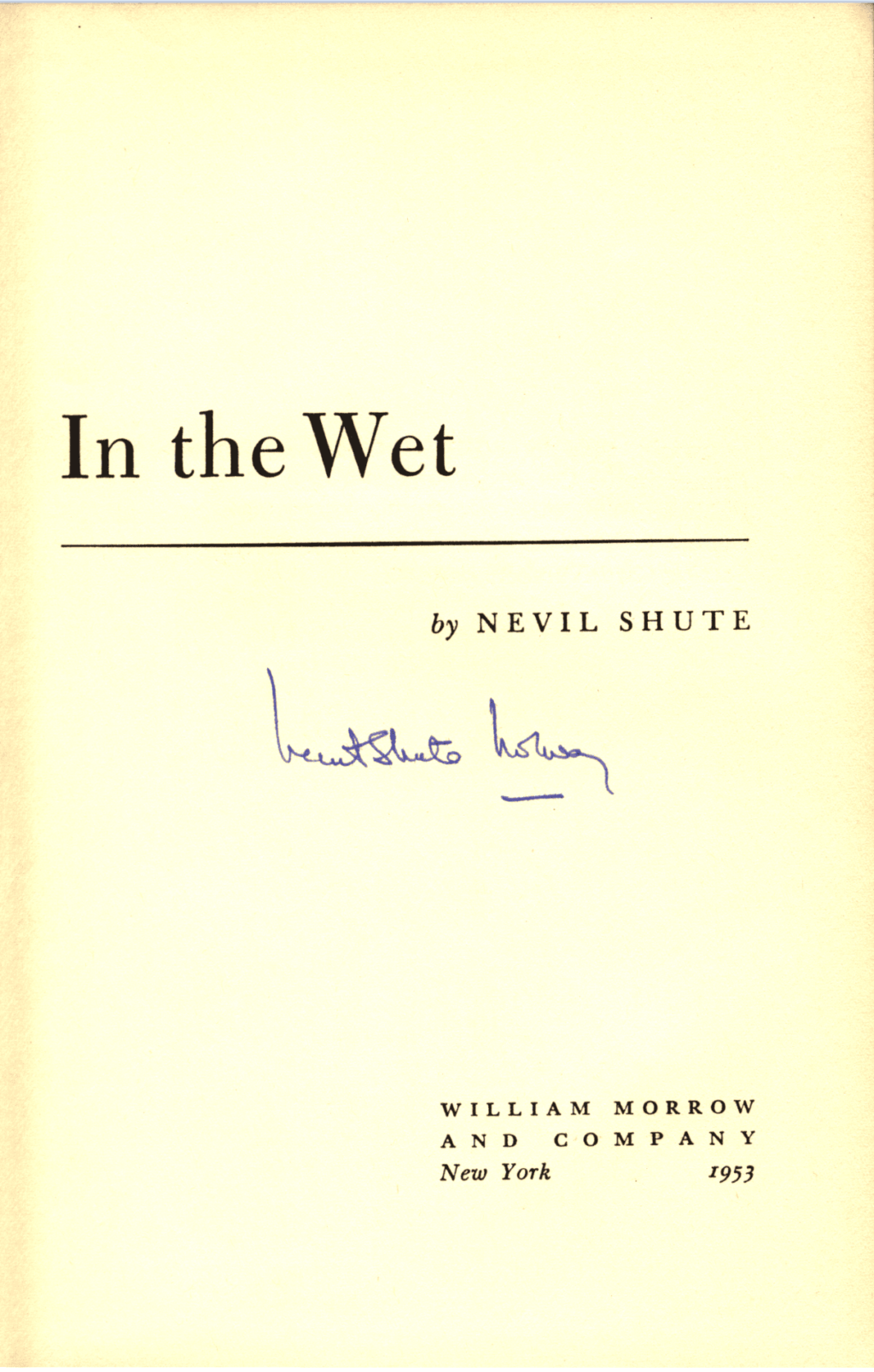

Nevil Shute, In The Wet (1953)

Nevil Shute Norway was a popular novelist who fled the ‘socialism’ of Britain’s Attlee Labour Government to make a permanent home in Menzies’s Australia.

Born in London in 1899 as the son of a postal clerk, Norway was a strong believer in the traditional British values of freedom and enterprise which he felt could only survive and prosper in places like Australia and Canada. Though he had been publishing novels since the 1920s, several of his most successful works were set in Australia, including A Town Like Alice (1950), Round the Bend (1951), The Far Country (1952) and In the Wet (1953).

The latter caused significant controversy. Published in the year of Elizabeth II’s coronation, it envisaged a dark future in which by 1983 the Queen would have to flee the persecution of a UK Labour Government and take up permanent residence in the antipodes. The protagonist David Anderson is a quarter-Indigenous Australian fighter pilot who had won fame in a 1970s war, and who has to personally escort the Queen into a safe exile.

Britain itself is pictured as hollowed out by mass emigration, as people had tried to escape high taxation, perpetual rationing, and falling living standards, which were all portrayed as the inevitable consequence of a long-term Labour administration. Meanwhile, Australia is prospering, absorbing most of the British migrants, and functioning under an innovative ‘multiple vote’ system which has saved democracy from its destructive tendency to denigrate the productive elements of society and encourage people to lean on the state. Each person is entitled to at least one vote, but additional votes can be earned for ‘education (including a commission in the armed forces), earning one’s living overseas for two years, raising two children to the age of 14 without divorcing, being an official of a Christian church, or having a high earned income.’ A meritorious seventh vote is ultimately awarded to Anderson by the Queen as part of the climax of the story – and functions as a modern knighthood.

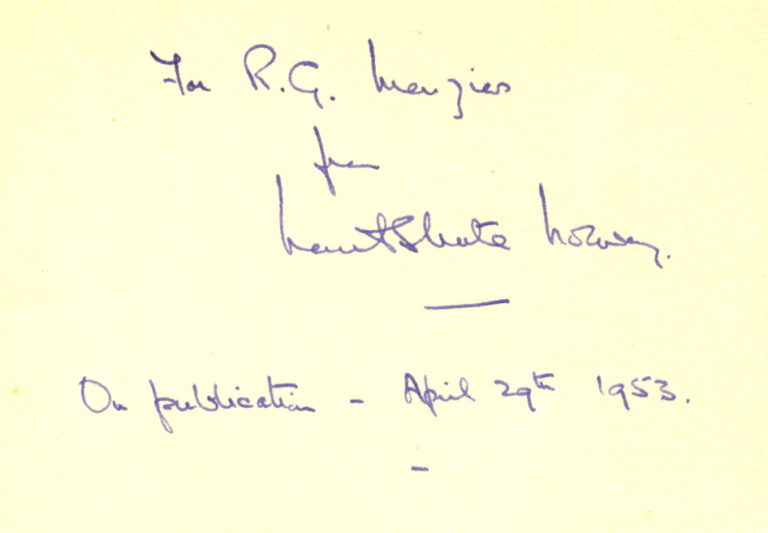

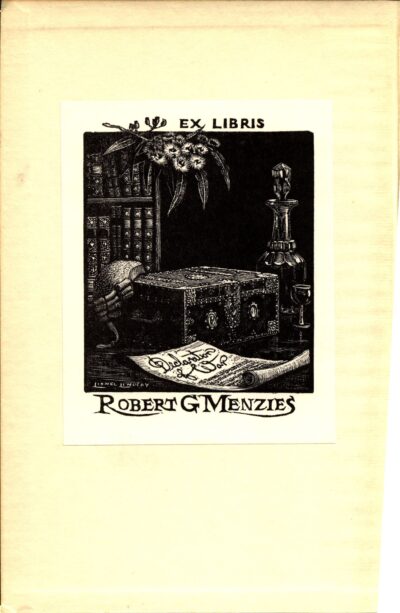

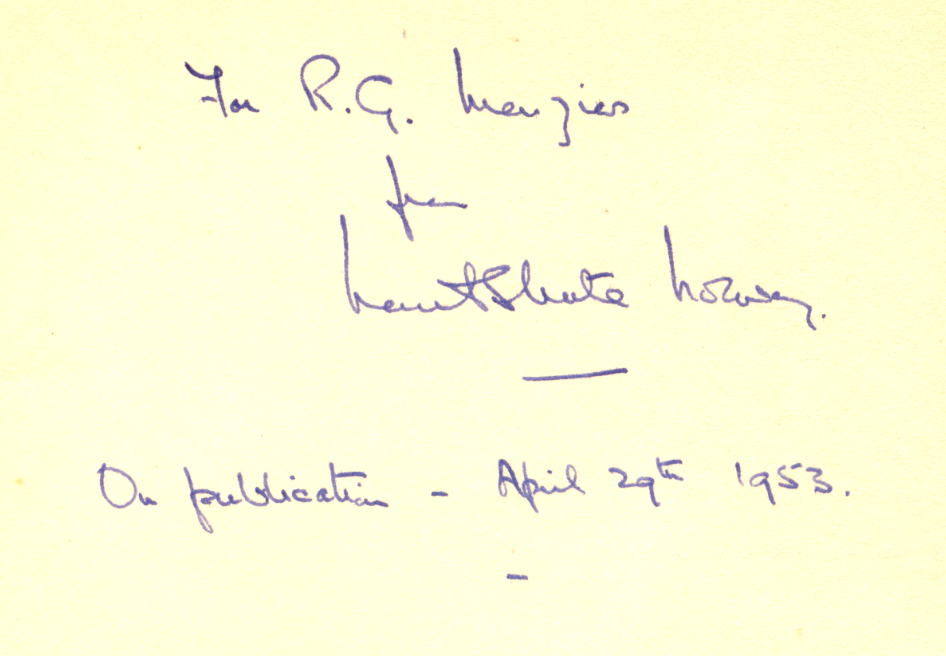

Norway obviously felt that the book was complementary to Menzies and the trajectory on which he had placed his nation, hence on publication the author immediately sent Menzies a personally inscribed copy. Norway however, seems to have been quite cut off from the history of Australian liberalism, a political tradition that Menzies upheld, and which itself had been responsible for abolishing plural voting (which allowed people to vote in more than one electorate if they owned multiple properties) under the emotive catch-cry of ‘one man one vote’. Nevertheless, the book remains a fascinating historical snapshot of how the 1949 election was seen to have sent Australia down a clearly divergent path from contemporary Britain. And to be fair to the author, the book has aged far better when it comes to issues of race, with Anderson overcoming clear prejudice to prove himself the hero in the end.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.