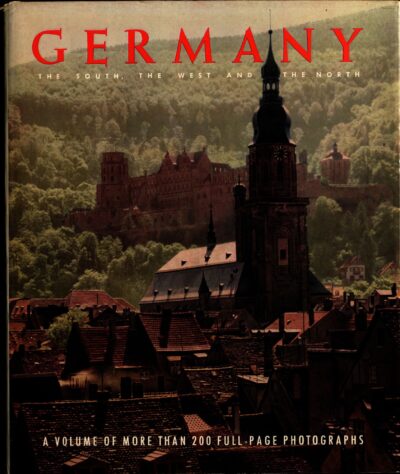

Paul Wolff, Germany: The South, the West and the North. A Volume of Photographs of Germany’s Countryside, her Cities, her Villages and her People (1950)

Just as Robert Menzies spearheaded Australia’s post-war reconciliation with Japan, his government likewise oversaw the normalisation of relations with the Federal Republic of Germany (aka West Germany). While regional proximity inevitably meant that this relationship was not as pivotal to Australia’s interests as that with Japan, it would similarly be shaped by key strategic, Cold War and economic concerns.

The West German Government with which Menzies would have to deal was that headed by Konrad Adenauer. Adenauer was a man whose career bears striking similarities to that of Menzies: he founded a mainstream centre-right party that would win office in 1949, oversee an incredible period of protracted economic growth, and only lose power after two decades. They likewise had similar approaches to governing, based on incremental policy change, expanding the middle class and emphasising home ownership. Jonathan Sumption made the comparison that:

‘Sir Robert Menzies was a liberal conservative, an individualist and a believer in the middle-class virtues of ambition, family loyalty and self-reliance. In all of these respects he was a man of his time, very much in the same mould as contemporary European statesmen such as… Konrad Adenauer in Germany.’

The first step in resuming regular relations between the countries led by both men occurred in August 1950, when Menzies announced that Australia would welcome a German Consul-General – a representative that would have no political functions but would help to facilitate and foster trade.

Then in January 1952 External Affairs Ministers Richard Casey announced that Australia was opening a full embassy in the West German capital of Bonn, in a reciprocal arrangement which saw a German Ambassador sent to Australia who would have a clear political role. Casey was well placed to nurture friendly relations with the German Government, as he had known Adenauer since 1925. His memoirs record a particularly jovial evening in which the two men enjoyed several bottles of Rhine wine and broke into a rendition of ‘Lorelei’ – much to the shock of the other German officials present.

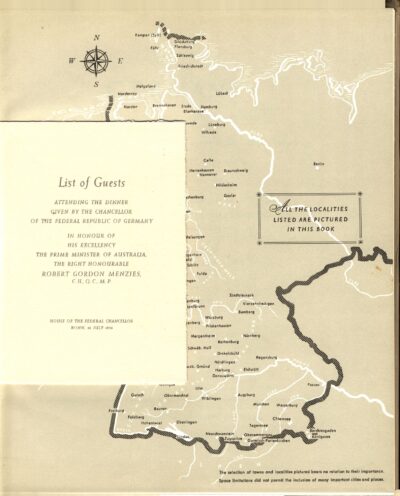

In 1956 Menzies went on a trip to Germany to ‘get to know Adenauer’, during which he praised Germany’s unparalleled economic recovery and sought to secure more German migrants to Australia – while admitting that Germany’s roaring economy meant that few would likely be found. Menzies pointed out that West Germany ranked 3rd on the list of Australian imports and 7th as a buyer of Australian goods, and he was able to persuade Adenauer to increase the import quota of Australian wheat by 100,000 tonnes.

Menzies also affirmed his support for West Germany’s attitude to its East German counterpart – namely that it sought reunification, but none that might jeopardise the successful liberal democracy the West was building. Throughout the Menzies era, the Australian Government refused to recognise the Communist Government of the ‘German Democratic Republic’, viewing it as neither legitimate nor democratic.

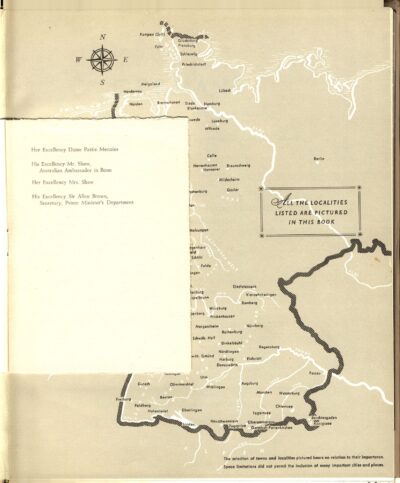

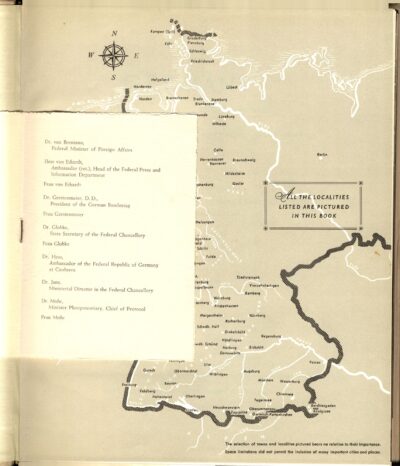

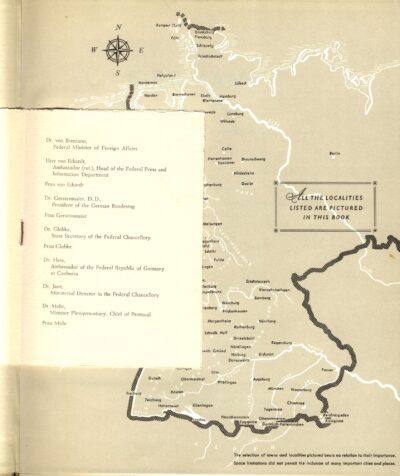

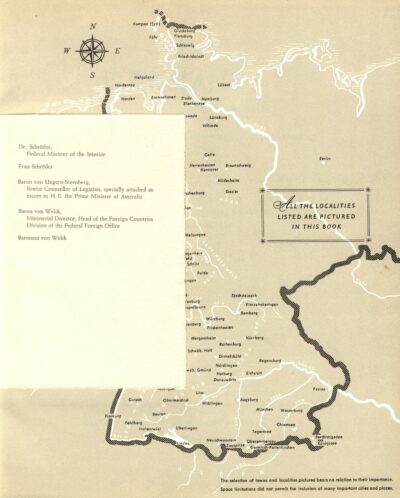

It was during the 1956 trip that Menzies was gifted his copy of Germany: The South, the West and the North, a book of images taken by the famed German photographer Paul Wolff. The book is thus an artefact of the bourgeoning Australia-Germany relationship, with the notable absence of ‘East’ from its title speaking to both the division of the country and the Oder-Nesse Line controversially redrawing its Eastern border.

By the later 1950s the hesitancy that had characterised Australia’s dealings with West Germany earlier in the decade had faded, and Menzies looked upon Adenauer as an important Cold War ally. That did not mean that they necessarily saw eye to eye on every issue. In 1959 Menzies acted as an emissary for the Macmillan British Government to try to persuade Adenauer and De Gaulle to agree to hold a summit with the Soviets over the status and administration of Berlin, but he was rebuffed by both. However, when the Berlin situation worsened in 1961 leading to the building of the infamous Berlin Wall, Menzies backed Adenauer’s position of seeking to uphold the ‘Berliners’ right of self-determination’ and was greeted with a public message of ‘joy and satisfaction’ from the West German Chancellor.

When Adenauer’s long reign ended in October 1963, Menzies paid him a tribute by saying that:

‘History will record the role played by Germany in the political and economic development of post-war Europe, and tributes will be paid to your outstanding leadership during these important years’.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.