W.S. Kent Hughes, Slaves of the Samurai (1946)

One of the defining features of the early Liberal Party was the large number of ex-servicemen it attracted. Indeed, one of the myriad of centre-right parties that were created during the disintegration of the UAP was even called the ‘Services and Citizens Party’, and it subsequently attended the Non-Labor Unity Conference and was absorbed into the Liberals. A handful of the so-called ‘49ers’, the large cohort of new MPs that came in with Menzies’s election victory in 1949, had not only fought in the war but even survived harrowing internment in Japanese prison camps. This makes it all the more remarkable that the Menzies Government was able to spearhead Australia’s reconciliation with Japan.

One such individual was Wilfrid Selwyn (Billy) Kent Hughes. Born in East Melbourne in 1895, Kent Hughes had enlisted in the AIF at the start of World War One. Ultimately joining the famous Light Horse, he would see action at Gallipoli, Sinai, Palestine and Syria, winning the military cross in 1917.

A talented sportsman who belatedly learned that he had won a Rhodes Scholarship after he enlisted, after the war Kent Hughes studied at Oxford and competed in the 1920 Olympic games. On returning to Australia he worked for his father’s publishing firm, and took a keen interest in politics, joining the conservative ‘Constitutional Club’ where he met and befriended Menzies. Despite being a year younger, Kent Hughes beat Menzies in the race to enter Victorian Parliament, and both would become members of the McPherson Government before jointly resigning to protest a sordid deal with the Country Party. The two men world later form the Young Nationalists, though Kent Hughes’s politics were to the right of Menzies’s and he even had a short flirtation with fascism.

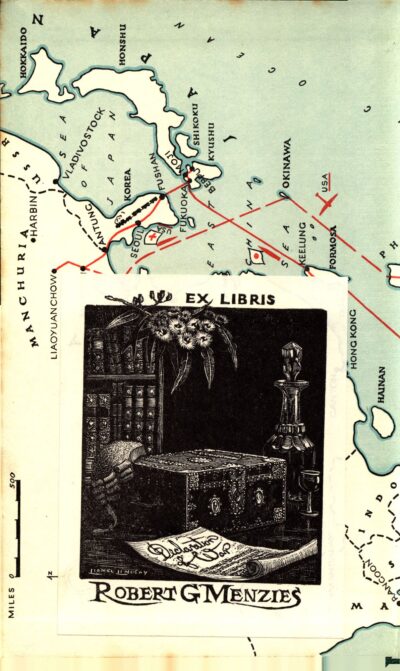

Staying in Victorian Parliament throughout the 1930s, Kent Hughes was Deputy Opposition Leader when World War Two broke out, and resigned the post (but not his seat) to rejoin the AIF. He would be captured during the Fall of Singapore and survive three horrific years in Changi, Formosa, and Manchuria. As a way of coping with the trauma, in captivity Kent Hughes would write an epic poem that was later published as Slaves of the Samurai.

Remarkably, Kent Hughes was re-elected as the Member for Kew in absentia in 1943 despite no-one being sure if he was even alive. On being liberated he would re-enter Victorian politics before being elected to the Federal seat of Chisolm in 1949. He would serve as Menzies’s Minister for the Interior and later Minister for Works and Housing, as well as taking charge of organising the Melbourne Olympic games.

However, perhaps Kent Hughes’s most striking political contribution was made during the debate over whether to ratify the San Francisco Peace Treaty with Japan. The ‘soft’ treaty was very generous to Japan, and became a matter of extreme controversy, with the Labor Party strongly opposed to it. Despite the horrors he had endured at the hands of his captors, Kent Hughes went into bat for the Government’s position, directly debating Opposition Leader HV Evatt both inside and outside of Parliament. Supporting the treaty as essential to the Cold War imperative of stopping the spread of communism, Kent Hughes explained that:

‘It is not easy for any ex-prisoner of war who was in the hands of the Japanese to talk about this subject. Some of the views that I hold may not coincide with the views of my former comrades in arms, but I shall not criticize them for that, because only an ex-prisoner of war can understand to the full the stresses, the strains and the emotions which play upon the mind and memory when we discuss a treaty of this nature with Japan so-soon after the end of the war. I assure honourable members that we have not forgotten. Ten years ago, when I was in Changi, and five and a half years ago when I was in Mukden, almost to the very day in each instance, little did I think that I should be to-day in my present dilemma as a member of an Australian Government confronted with a proposition of this nature.

Certain events in the life of a man can never be forgotten even to his dying day. Only those who have passed along the purgatorial path of ill-treatment, starvation, murder, bashing and every other conceivable kind of brutality, and only those who have been driven to work in fever-stricken jungles, in torrential rain or in sub-arctic cold, can fully realize what goes on in the minds of men like myself and those who were my comrades. Only those who have had such experience know how often we woke screaming after we returned home, and still are awakened by nightmares, but thank God at longer intervals. In fact, though it seems silly, one almost hears in one’s ears the strident, harsh cry, “Kirai” when one bows to you each day, Mr. Speaker. “Kirai” was the command upon which we had to bow to the Emperor each morning and to every Japanese sentry about the place. Therefore, I may be forgiven if I speak with some emotion on this subject. My former comrades will understand, even though our views may differ. We fully realize the futility of trying to build anything permanent on a foundation of continuous desire for revenge or continuous hatred…

[E]very one of us hopes that this treaty will remove some causes of friction between nations. We hope that it will give a new chance to a nation that in recent years has been guilty of the most criminal brutality, the memory of which engenders in the hearts of every ex-prisoner of war and every citizen of Australia a feeling that is hard to banish. One can only hope and pray that the glimmer of light will not be a false dawn but will be the true dawn of a new era, perhaps to be named, like the seas that surround us which so recently ran with blood in the war, the “pacific” era’.You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.