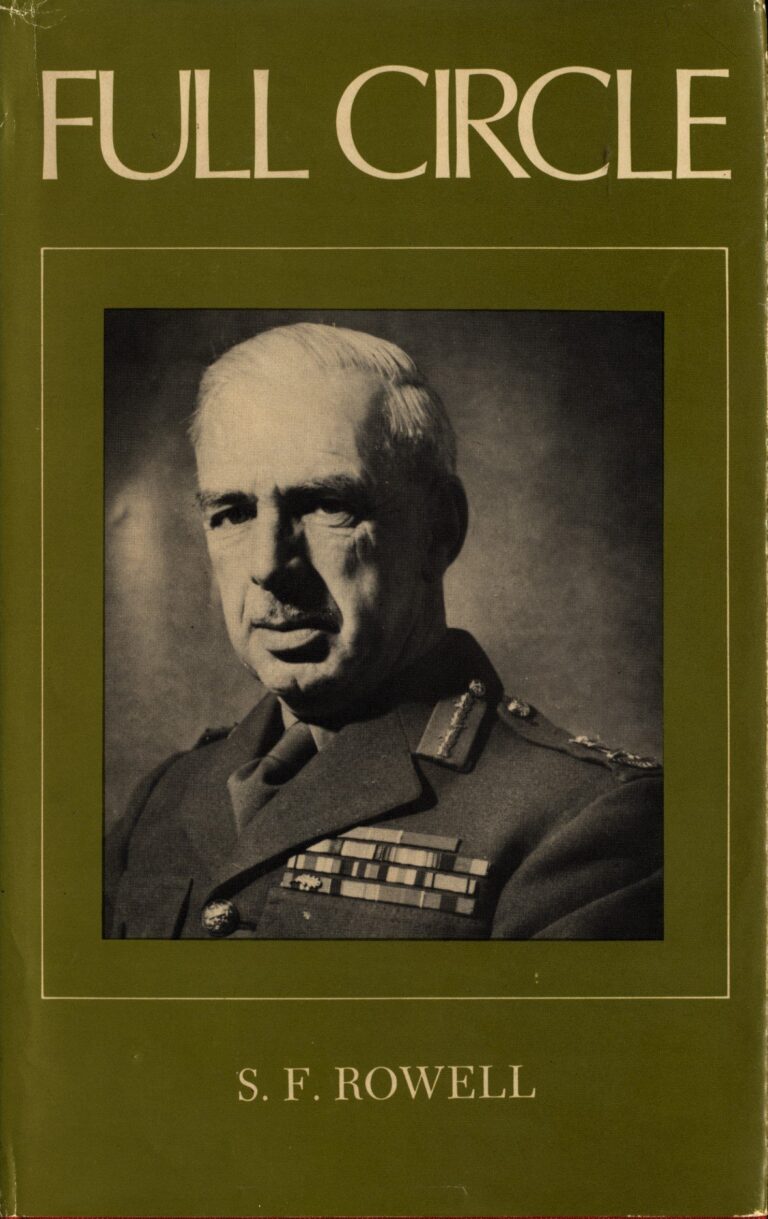

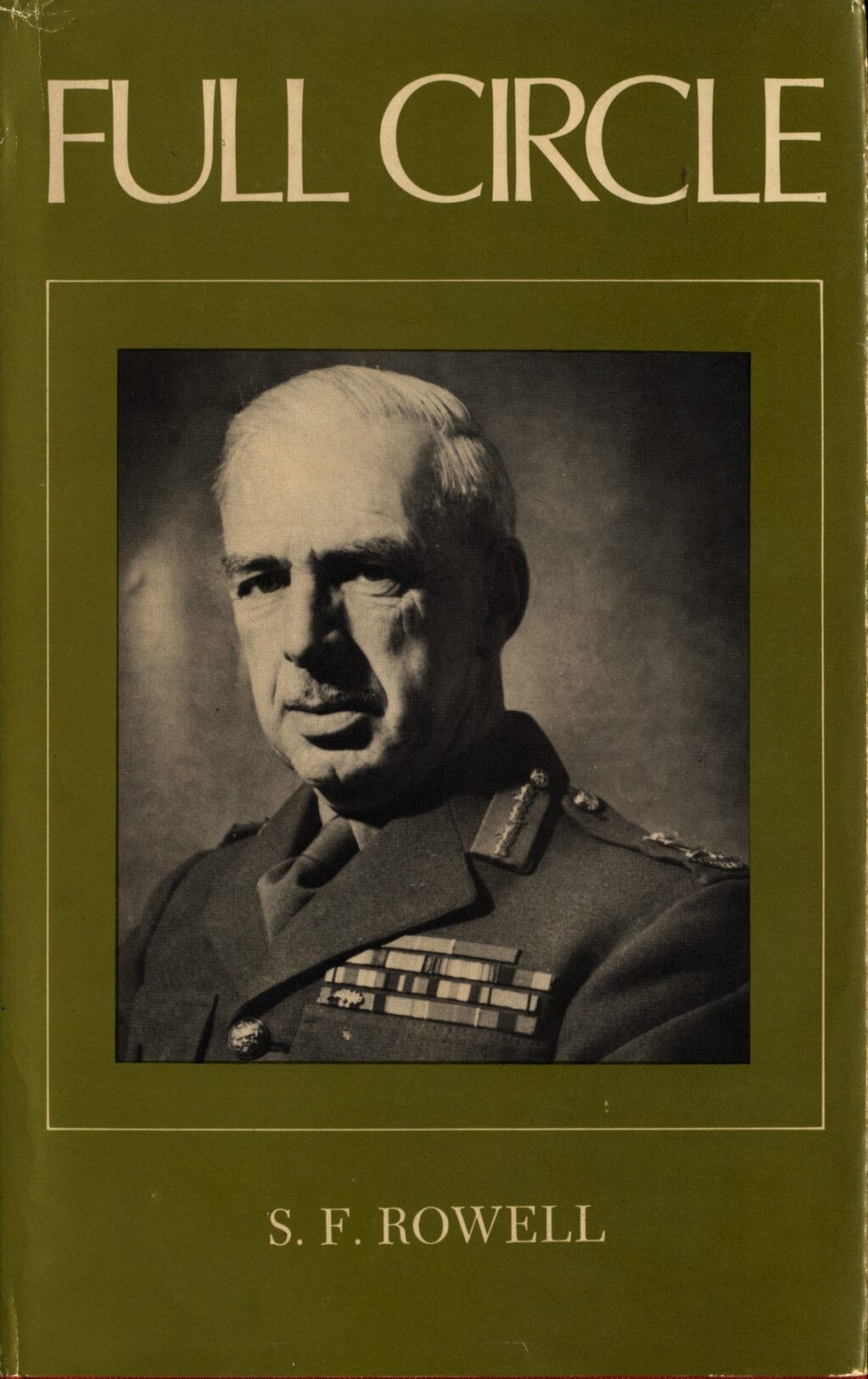

S.F. Rowell, Full Circle (1974)

Sydney Francis Rowell was an Australian general who headed the Australian Army during the Korean War. He is now best remembered for his role in the Kokoda Track campaign and his infamous dismissal from command.

Born in Lockleys, South Australia just five days before Menzies was born in Jeparit, Rowell was the son of a decorated soldier who would go on to Command the South Australian Brigade. He was raised for a military career, serving as his father’s ‘unofficial batman’, before becoming one of the first class of cadets to enter the Royal Military College at Duntroon.

Although Rowell was well-placed to play a leading role in WW1, a combination of pneumonia, a broken leg, and then typhoid fever meant that he saw little action. Nevertheless, he spent the inter-war years climbing the army ranks and furthering his military studies in Britain. By the time WW2 broke out Rowell became Brigadier in Thomas Blamey’s General Staff, accompanying him to the Middle East. The two men had a falling out during the exhausting Greek campaign, hence it was something of a relief when Rowell was given his own command in 1942, taking charge of Australian troops in New Guinea during the Kokoda campaign.

Rowell arrived in a difficult situation. Supplies were lacking, his militia had less training than the AIF, and conditions in the mountainous jungles were extremely arduous. Despite having the odds stacked heavily against them, Rowell’s Australian troops engaged in what was essentially a successful fighting retreat along the track, which gradually drained the enemy’s energy and resources. Rowell decided to draw a final line at Imita Ridge, nearing Port Moresby, stressing the fact that ‘however many troops they enemy has, they must all have walked from Buna’ and therefore be utterly sapped. This proved the case, and the Japanese commanders were eventually forced to give the order to ‘advance to the rear’, there allegedly being no Japanese word for ‘retreat’.

No sooner had the tide of the battle turned in Australia’s favour, then Rowell would be brought down by a combination of politics and ignorance. Far away from the fighting, American General Douglas MacArthur became convinced that Rowell’s retreat was evidence that he was a ‘defeatist’ and MacArthur put tremendous pressure on Prime Minister John Curtin to do something about it. In the end, Blamey was sent to New Guinea and ended up dismissing Rowell – though most modern historians maintain that this was the wrong decision. When Blamey tried to add a further humiliation by reducing Rowell’s rank to Colonel, political pressure was exerted the other way, with Rowell writing to Opposition Leader Robert Menzies, and the matter subsequently being raised in the Advisory War Council as well as in Parliament. In the end Rowell was ‘banished’ to positions in Cairo and then London, far away from where most Australians were fighting.

After the war Rowell’s rank was reinstated, and he played a crucial role in reorganising the army, as well as following Chifley’s orders to break the 1949 coal strike by sending in troops to work the mines. On returning to the Prime Ministership, Menzies appointed Rowell Chief of the General Staff, making him the first Duntroon graduate to head the Australian Army. He would go on to oversee the Australian involvement in the Korean War, before retiring in 1954.

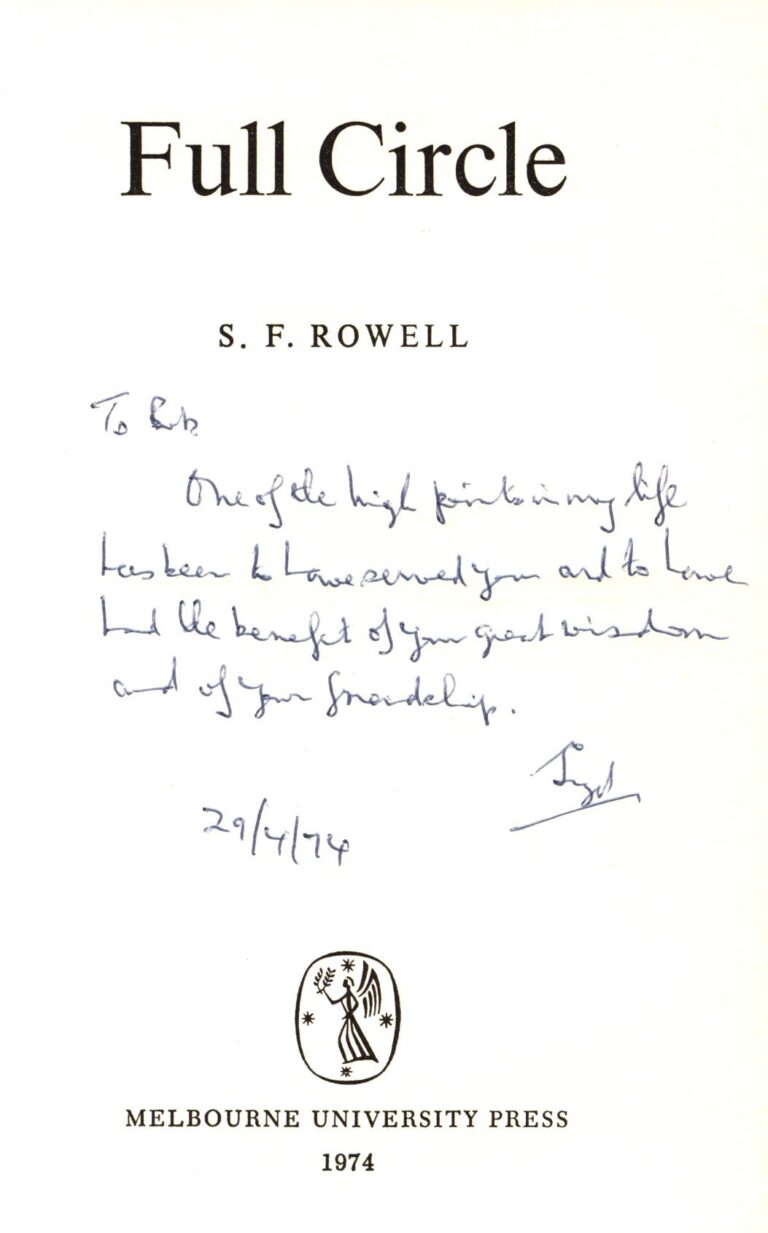

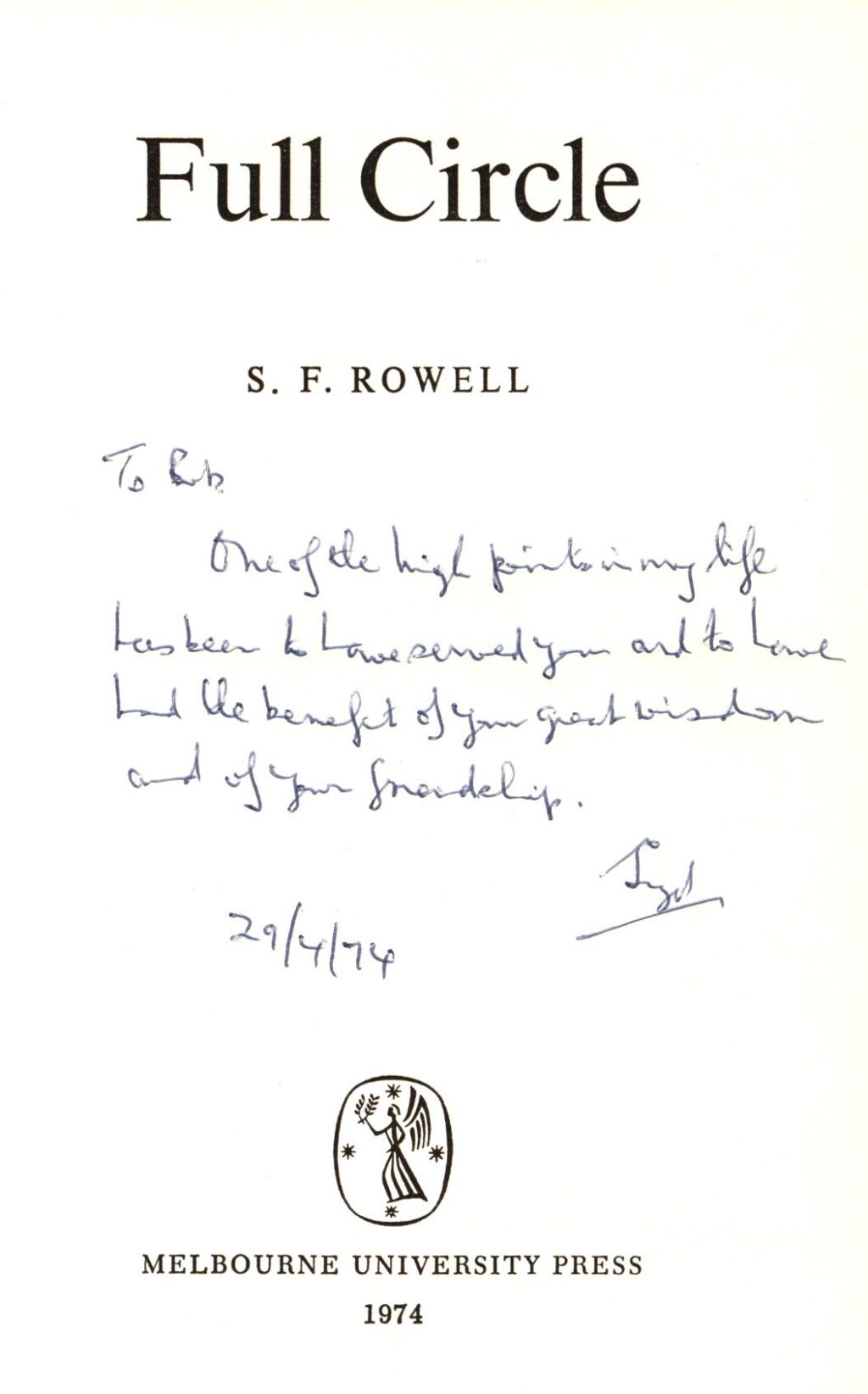

When Rowell published his memoir in 1974, he sent Menzies a copy inscribed:

‘To Bob,

One of the high points in my life has been to have served you and to have had the benefit of your great wisdom and of your friendship. Syd / 29/4/74.’

A touching tribute to their relationship, and one made extra pertinent by Rowell’s previous negative experience with politics.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.