L.S. Amery, The Forward View, 1935

Leo Amery was a British Conservative politician who held a number of Cabinet positions, most notably Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1924-29 during which time he frequently engaged with the Bruce-Page Australian Government in pursuit of imperial trade preference. Born in India, he attended the famous Harrow School as a contemporary of Winston Churchill, and could speak numerous languages including Hindi, French, German, Italian, Bulgarian, Turkish, Serbian and Hungarian. He is now perhaps best remembered as an opponent of appeasement who delivered a withering attack on Neville Chamberlain that presaged the division that drove him out of office.

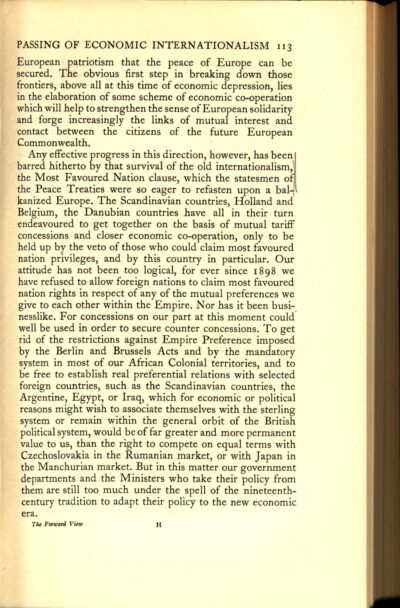

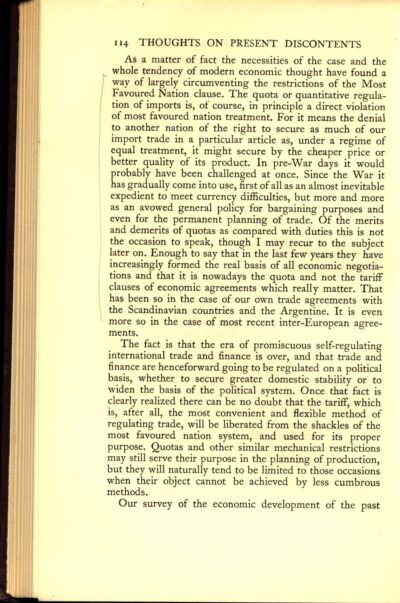

The Forward View is a response to the crisis that liberal democracy was experiencing in the 1930s. It is a defence of ‘British freedom’, rooted in history, culture and icons like Magna Carta, as something more permanent and successful than abstract philosophical liberalism, which was failing to achieve what it had promised and succumbing to tyrannies like fascism and communism. It then expands into an argument for the benefits of a revitalised Empire over the utopian liberal internationalism of the League of Nations, from which the aggressive Germany had already withdrawn. W.K. Hancock said of the book:

‘The author’s outlook is dominated by his repudiation of the liberal philosophy which prevailed in the 19th century. He does not deny that this philosophy served in its day a necessary purpose of emancipation, nor does he carry his repudiation of it to totalitarian lengths. Indeed, one of his quarrels with arithmetical democracy is that it prepares the way for dictatorship by working through majority tyranny to the party-state. If his “forward view” places “British freedom” in the centre of the picture, this is because he believes it to be “something much older, more deeply rooted in and intertwined with our being, more instinctive and truer to life than the abstract doctrines of individualist liberalism which are the real object of attack today”.’

Menzies’s copy was a gift given to him directly by Amery in 1935. The two men appear to have been quite close friends, and the Menzies Collection contains a large number of books gifted from Amery over several years, of which this is the earliest. The book has markings in the margins in pencil throughout and seems to have been intently read, which would make sense, as we know that during the 1930s Menzies was similarly preoccupied with the idea that liberal democracy was assailed by threats.

The book helps to contextualise Menzies’s liberalism, and demonstrate why it easily blended with aspects of his philosophic outlook which were more conservative in nature. It attests to the thesis of the recent book The Forgotten Menzies by Stephen Chavura and Greg Melleuish, which argues that modern debates over whether Menzies was ‘liberal’ or ‘conservative’ are anachronistic and unhelpful.

Menzies never went so far as to openly repudiate liberalism in the manner of Amery, but he was similarly sceptical about approaching freedom in a doctrinal or theoretical way. Menzies stressed the importance of a culture of liberty, which he associated with ‘Britishness’, and seeking the tangible reality of freedom rather than an abstract ideal. He was particularly critical of utilitarianism, which had been intimately associated with the 19th century reform movements, as a ‘Frankenstein monster which may yet destroy us’ by reducing humanity down to its base wants and pleasures, and ignoring the ‘humane and imperishable elements in man’. He was also a realist when it came to international bodies, frequently stressing the importance of national sovereignty and a degree of subsidiarity.

You might also like...

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to hear the latest news and receive information about upcoming events.